On Franklin Patterson’s farm in the interior of Alabama, there was a practice that had become as much a part of the landscape as the cornfields themselves—a practice rooted in cruelty, designed to instill fear and control.

Franklin, a man hardened by years of running a plantation, was known for his strict, unforgiving discipline.

The punishment of the “human scarecrow” was something he had inherited from his father, a grotesque ritual that made an example of anyone who dared defy him.

It began with the pillory, followed by lashes from a whip until the skin was torn open, then the days of being tied to a post under the sun, starving, dehydrated, until the body could no longer endure.

The final humiliation was always the beating that followed, designed to ensure that the lesson was never forgotten. This, Franklin believed, was the best way to keep everyone in line.

If one person broke, others would fall in line by sheer example.

The post, standing tall in the middle of the farm’s fields, was not a mere structure. It was a tool of control, placed in a spot where everyone could see.

When anyone passed by, it was impossible not to notice. To outsiders, it was a symbol of Franklin’s absolute dominance; to the enslaved people, it was a reminder of their place in the world.

Patterson’s farm had become infamous in three counties. The mere mention of his name in the town taverns prompted a mixture of admiration and discomfort.

The other farmers admired Franklin’s ability to maintain such strict control, but they knew there was a darkness behind that discipline.

Franklin’s farm was profitable—his lands stretched over hundreds of acres, producing cotton and corn—but the true cost of that success was hidden in the shadows.

One of Franklin’s favorite methods for ensuring that no one forgot who was in charge came after a failed escape attempt.

A young man named Samuel, desperate to be free, tried to flee the plantation. He was caught three days later, starving and lost in the swamp.

Franklin, enraged by the boy’s defiance, decided that the punishment needed to be a spectacle. He had the post constructed in the shape of a cross and had Samuel hung there for five full days.

The boy didn’t survive the ordeal. By the fourth day, Samuel was dead, his body left to hang in the sun for another day as a grim reminder. Franklin told his overseers, “The lesson must be clear.”

For months, the post stood empty, a silent monument to Franklin’s power.

But it was never truly vacant in the minds of those who worked the land. It was a constant threat—a warning that the same fate could befall any one of them.

Franklin had inherited the farm from his father when he was just 25.

Along with the property, he inherited 43 enslaved people, and over the years, he expanded, growing both the farm and his wealth.

He was a man of few words, but when he did speak, it was often to reinforce the idea that obedience was the key to survival.

“If you want respect,” he often said with a cold smile, “you must first show them what happens to those who don’t respect you.”

The overseers on Franklin’s farm were extensions of his will, each one carefully chosen for his ability to enforce Franklin’s rules.

Silas Green, the oldest and cruelest overseer, was a man whose sunken eyes and thin frame belied the sadism that lay beneath the surface.

He had been with the farm since Franklin’s father had run the operation, and after years of serving as an overseer, Silas had become a fixture of the place.

He relished in the power he held over the enslaved people, and his enjoyment of their suffering was evident in the way he moved—methodical, deliberate, as if he knew every corner of the land and every moment in a person’s life.

Horus, large and brutish, was less intelligent but more than capable of following orders and using violence to maintain control.

Ezekiel, younger and more nervous, worked out of fear—fear of losing his job, fear of Silas, and most of all, fear of Franklin.

Together, the three overseers worked in a near-constant state of surveillance, watching the enslaved people closely and making sure that no one stepped out of line.

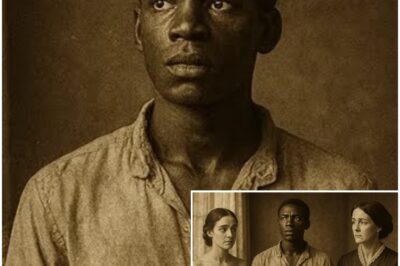

Gideon, who had been bought five years earlier at an auction in Montgomery, was the largest and strongest man Franklin had ever seen.

At over 2 meters tall, with broad shoulders and arms like tree trunks, he was a walking wall of muscle.

The enslaved people called him “the giant,” and though he was not the type to challenge authority, there was something about him that set him apart.

He wasn’t broken. And that made him a threat in Franklin’s eyes.

Gideon had been purchased to help open new land, cut down thick trees, and pull up deep stumps.

He worked in silence at first, cutting more wood than anyone else, carrying logs that two men should have been needed to lift, digging ditches with impressive speed.

Franklin’s overseers had no complaints about his work; Gideon didn’t resist, didn’t ask questions, didn’t challenge their authority.

But over time, the other enslaved people began to look up to him. He had a natural leadership quality, one that couldn’t be ignored, even if he wasn’t trying to lead.

When a fight broke out between two men over a tool, it was Gideon who stepped in between them, saying something low that Silas couldn’t hear.

The two men stopped fighting immediately and returned to their tasks. Silas, standing nearby, noticed the change but couldn’t quite place it. The situation had resolved without violence, and that disturbed him.

It disturbed him because it wasn’t the way things were supposed to work. He had learned that a problem should be solved with force. And yet, Gideon had solved it with something else.

It wasn’t long before Silas started watching Gideon more closely.

He noticed how the other enslaved people gravitated toward him, how the children approached him without fear, how the older women asked him for help without hesitation.

There was respect for him, and respect, Silas knew, was dangerous.

Franklin was no fool. He saw the growing respect for Gideon too, and it made him uneasy.

He’d seen how other plantations had dealt with strong men who had earned the respect of their fellow slaves—rebellions, organized escapes, and worse. Franklin couldn’t afford for that to happen on his farm.

One day, a small amount of corn went missing from the storage barn. It was the kind of theft that could easily be overlooked, but Franklin couldn’t let it slide.

He demanded to know who was responsible. Silas, eager to exploit the situation, whispered in Franklin’s ear, “I think the giant knows. He knows everything that happens in the slave quarters. He’s the one people turn to when things go wrong.”

It was a lie. But it didn’t matter. Franklin had already made up his mind. He didn’t need proof; he just needed a reason to break Gideon, to remind him—and everyone else—that no one was untouchable.

The next morning, Silas and the other overseers arrived where Gideon was working, cutting logs near the edge of the farm.

“Drop that and come here,” Silas barked.

Gideon, knowing resistance would only make things worse, set the axe down and walked towards them. “What is it?” he asked calmly, not yet understanding the trap being set for him.

“Someone’s been stealing food,” Silas accused, his voice dripping with false sincerity. “And I think you know who it is.”

“I don’t know anything about that, sir,” Gideon replied, keeping his voice steady.

“You know who it is, and I think it’s time you’re taught a lesson,” Silas sneered. “The boss says you’ll serve as an example.”

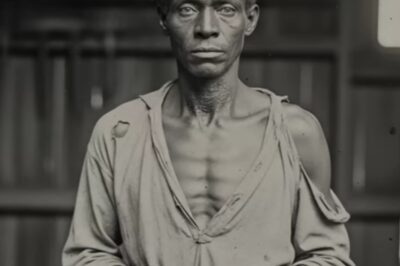

And so, Gideon found himself dragged to the post in the center of the plantation—the very post that had become a symbol of Franklin’s iron fist.

Tied to the post, exposed to the scorching sun and the elements, Gideon endured the lashes, one after another, as the whip tore into his flesh.

Silas smiled to himself as he struck the giant, but something inside him began to crack when Gideon didn’t cry out. When Gideon didn’t break.

By the second day, the other enslaved people on the farm were speaking in hushed tones, but no one dared look directly at the post. It was a silent understanding: If Gideon, the strongest of them all, could be broken, none of them were safe.

Lena, a 12-year-old girl who worked in the big house, watched from a distance. She had seen enough.

She had witnessed the cruelty and the fear, but she also saw something in Gideon that no one else could see. Something inside her shifted. She couldn’t let him die there. She wouldn’t.

That night, Lena snuck out of the big house with a basket of food and water.

She moved quietly through the dark, avoiding the overseers’ patrols. When she reached the post, she whispered, “It’s Lena.”

Gideon, weak and feverish, barely managed to lift his head. “Go away,” he whispered, his voice barely audible. “It’s not safe.”

“No,” Lena replied firmly. “You’re not alone.”

And so, night after night, Lena returned with food and water, sustaining Gideon when he could barely keep his eyes open. Each night, he grew stronger, his will to survive ignited by the small acts of kindness she gave him.

By the fourth day, Gideon was still alive. And something inside him shifted. He wasn’t just surviving—he was plotting.

The storm that night would change everything. The overseers, thinking Gideon would be too weak to move, went to bed.

And Gideon, still wounded but determined, began to work at the ropes that held him. Slowly, carefully, he freed himself, and with every ounce of strength left in his body, he crawled into the swamp.

The farm, once a place of fear and oppression, was now the site of something different. Something Franklin never could have predicted.

Lena, with the help of others, began to prepare. It was time to leave. No one would ever be the same again.

News

The Mother and Daughter Who Shared The Same Slave Lover… Until One of Them Disappeared

The Rosewood Curse: A Love Written in Fire In the sweltering heat of August 1842, the Rosewood plantation lay bathed…

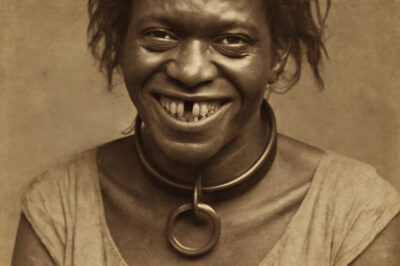

The Master Bought a Toothless Slave To Amuse His Guests…Then She Called Him by His Childhood Name

The Debt of the River: A Legacy of Ashes In the spring of 1853, on the outskirts of Natchez, Mississippi,…

Tennessee 2003 Cold Case Solved — arrest shocks community

The sun was beginning to dip beneath the horizon on the last weekend of July 2003, casting an amber glow…

13-Year-Old Sold to 51-Year-Old Plantation Owner… 8 Years Later, She Was His Worst Nightmare

The Hartwell Massacre: The Story of Rebecca’s Revenge and the Price of Justice The iron gate of the kennel yard…

A young Black girl was dragged into the kennel to be humiliated, left before 10 hunting dogs — but…

The Silent Bond: Naomi and Brutus’ Fight for Survival The iron gate of the kennel yard swung open with a…

Silas the Silent: The Slave Who Castrated 8 Masters Who Used Him

The Silent Revenge: The Story of Silas the Silent In the heart of South Carolina’s low country, the year 1836…

End of content

No more pages to load