The Debt of the River: A Legacy of Ashes

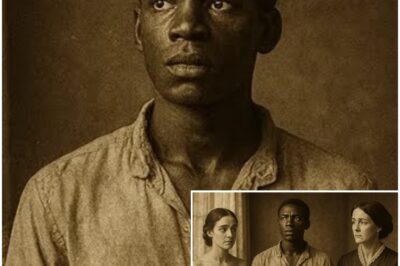

In the spring of 1853, on the outskirts of Natchez, Mississippi, a new curiosity arrived at the Fairmont plantation.

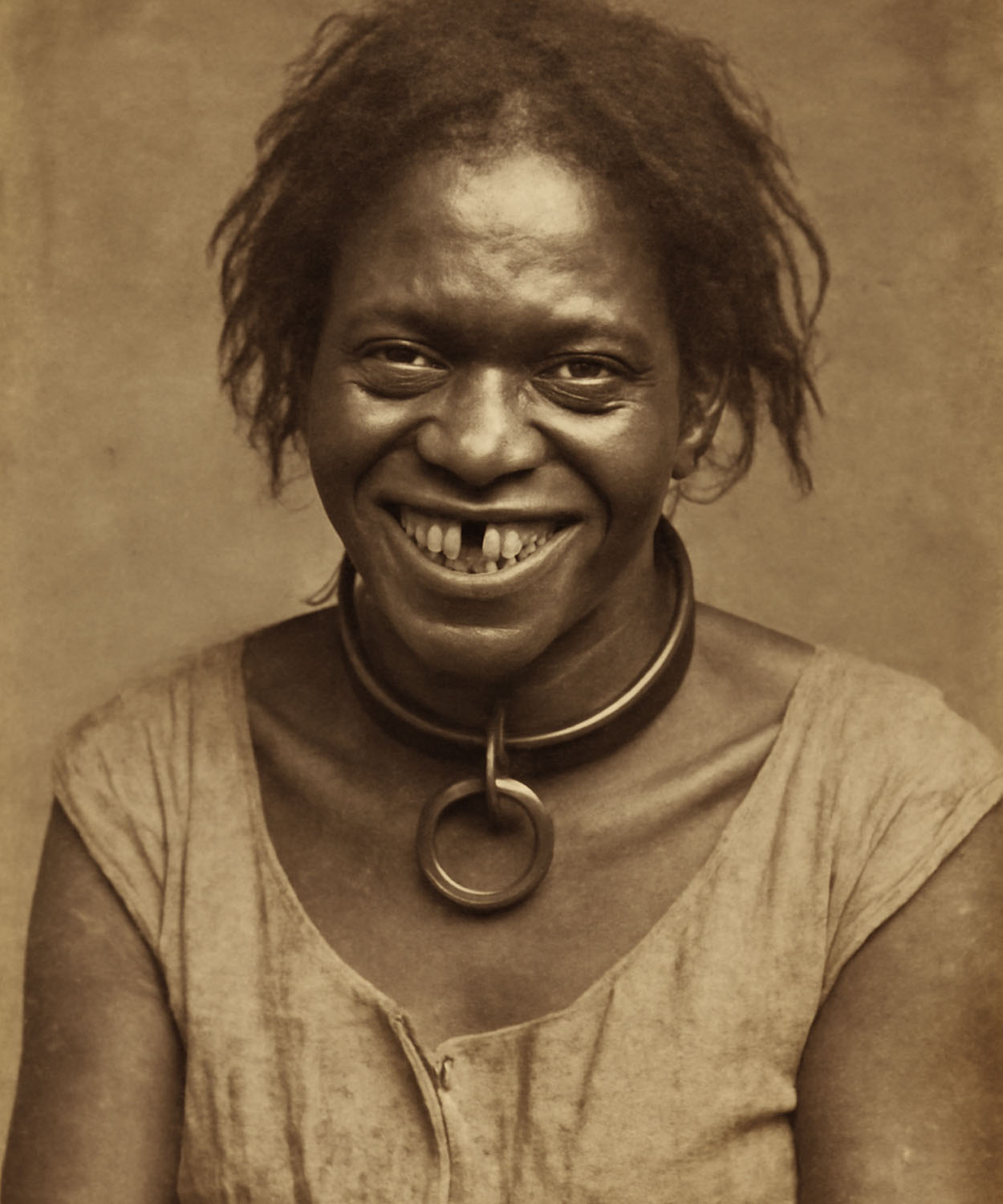

Her name, or what little remained of it, was Minnie.

She was old, small, toothless, and half-blind—her frail body appeared too weak to lift a broom, let alone labor in the cotton fields.

But Master Henry Fairmont, a man known for his cruel disposition, did not buy her to work.

He bought her for laughter.

For $10, Henry declared Minnie the perfect entertainment for his dinner guests, a living jest to break the monotony of their wine-soaked evenings.

But Minnie did not behave as the others expected.

She laughed at the wrong times, hummed to herself in an old dialect that made even the hardened field hands uneasy, and, once, in front of everyone, called her new owner by a name no one on the plantation had ever heard: Hen Hen.

The table fell silent.

The name hung in the air like a ghost.

Henry Fairmont had not been called that since he was a child, and only one person, a long-dead figure buried deep in his past, had ever called him that.

From that night on, the laughter on the Fairmont plantation died.

The auction yard reeked of sweat, dust, and molasses—a smell that clung to your throat long after you left.

It was a Saturday morning, and the traders shouted over the cries of children and the crack of whips.

Slaves stood on raised platforms, their bodies prodded and their teeth inspected like livestock.

Henry Fairmont stood near the front, his gloved hands clasped behind his back, a silk hat tilted just enough to hide the boredom in his eyes.

He had come not to buy workers—his fields were already full—but to amuse his dinner companions, the kind of men who enjoyed cruelty as easily as they enjoyed cigars.

“Got something special here, gentlemen!”

The auctioneer hollered, his voice carrying over the crowd.

“A real old one, but spry.

Can still talk, can still sing, and don’t complain none.

Look at her smile.”

Two handlers dragged Minnie forward.

She shuffled into the light, stooped and thin, her gray hair sticking out from beneath a ragged kerchief.

Her gums shown where teeth had once been, but her eyes—pale and strange—held something alive in them, something unbroken.

The crowd laughed.

“She ain’t worth feeding,” one man shouted.

“Give her a broom and call her a ghost,” another jeered.

But many only smiled. A wide, strange smile that made her wrinkles fold like paper.

“Good morning, chillin,” she said in a voice as soft as worn cloth.

Henry’s lip curled. “How old is she?”

“Can’t say, sir.”

“Near 70, maybe 80,” said the auctioneer.

“They say she’s from Carolina Way.

Got a mouth on her, though.

Keeps talking nonsense about things that happened long before any of us was born.

I’ll let her go cheap.”

Henry raised an eyebrow.

“How cheap?”

“$10?” the auctioneer suggested with a laugh.

“A snort rippled through the crowd. $10 for a ghost?”

someone murmured. The crowd chuckled.

Henry turned the silver coin between his fingers, amused.

$10 was nothing—a trifle to buy a moment’s laughter.

“I’ll take her,” he said, flipping the coin toward the block.

The gavel fell with a crack, and just like that, Minnie became the property of Fairmont Plantation.

The wagon ride back to the plantation was silent, save for the creak of the wheels and the groan of wood. Minnie sat across from Henry, her hands folded neatly in her lap, her eyes half-closed as if in prayer. Henry leaned back, studying her.

“You know where you’re going, old woman?” he asked, breaking the silence.

“Yes, sir,” she said softly. “I’ve been there before.”

He frowned. “You’ve never been to my plantation.”

Minnie smiled that same unnerving, empty smile. “Maybe not yours, Hen Hen.”

The name dropped between them like a stone. Henry sat forward sharply.

“What did you call me?” he demanded.

She tilted her head. “Just a name, I remember, that’s all. Don’t you like it?”

His hand twitched toward his cane, but something in her tone stopped him.

He told himself it was coincidence—some senile old slave babbling—but deep in his stomach, a long-buried unease began to stir.

When they arrived at the plantation, the field hands paused their work to watch. The mistress, Elellanor Fairmont, came out onto the veranda, her expression one of mild disgust.

“What in heaven’s name is that?” she asked, pressing a lace kerchief to her nose.

“Our new entertainment,” Henry said dryly. “She’ll keep the guests laughing.”

Elellanor’s eyes flicked over Minnie, unimpressed. “She looks like death itself.”

“Then perhaps she’ll remind them how lively they are,” Henry said, stepping inside.

That evening, the dining hall glowed with oil lamps and laughter. Guests reclined in velvet chairs, glasses of port in hand. Henry stood at the head of the table, a showman in his own house. He clapped his hands.

“Bring her in.”

The door opened. Minnie shuffled forward, her bare feet whispering against the wood.

The guests laughed at once—at her size, her stoop, the way her head barely reached the table’s edge. Henry grinned.

“Well, Minnie, can you sing for us? Can you dance?”

Minnie looked around the room, her eyes sweeping over the golden glass and smoke, and smiled faintly.

“I can tell a story, master.”

The guests cheered. Henry gestured for her to begin. She closed her eyes and started to hum—a slow, rhythmic tune that made the air itself seem to thicken.

Then, in a voice that trembled but never broke, she began to speak.

“There was a boy once who liked to steal apples from his mama’s kitchen.

She used to call him Henhen when she caught him, ‘cause he’d puff up like a little rooster, trying to hide what he’d done.”

Henry froze. The laughter faded.

“How do you know that name?” he demanded, his voice sharp.

Minnie looked up at him, her cloudy eyes unblinking.

“Because, child,” she said softly, “I was there when your mama stopped calling you that.”

The room went still. Henry’s cane slipped from his hand. Outside, thunder rolled across the hills, distant, patient, like something that had been waiting a very long time.

The morning after Minnie’s unsettling story, Fairmont Plantation woke in uneasy silence.

The laughter that usually followed Henry’s dinners had soured into muttered questions.

Some of his guests had left before sunrise, claiming early business in Natchez.

Others whispered about the way the old woman’s song had made the lamps flicker and the air grow cold.

Henry refused to speak of it. At breakfast, he dismissed his wife’s probing questions with a flick of his hand and an empty smile.

“Old women say foolish things,” he muttered. “She’ll keep to the kitchens from now on.”

But by the end of the week, Minnie had become the talk of the entire house.

The servants said she walked the halls at night, humming that same nursery tune.

They said she never slept, that she could be found sitting near the fireplace before dawn, staring into the ashes as though waiting for something to rise from them.

And worst of all, she had begun calling him Hen Hen again.

Never when others were around. Always when they were alone.

“Good morning, Henhen,” she’d say softly as she poured his coffee.

Or when she passed him in the hall.

“Mind your step now, boy. Mama don’t like scuffed boots.”

Each time Henry’s stomach twisted.

He told himself it was mockery—a way to amuse herself before death—but she said the words with such familiarity, such fondness, that the walls of his composure began to crack.

One afternoon, after returning from the stables, Henry found her in the nursery—a room that had been locked for over a decade.

Dust covered the toys, the wooden cradle, the faded wallpaper painted with sheep.

No one had entered since their only child had died there ten years before. Yet there she sat, rocking slowly in the chair near the window, humming.

Henry’s heart lurched.

“How did you get in here?” he demanded.

Minnie didn’t look at him.

“Door was open. Henhen, it called me.”

He strode forward, seizing the back of the chair.

“Don’t call me that again.”

She turned her gaze to him, unafraid.

“Your mama used to say that too when she was angry. You got her eyes, you know. Same storm in ‘em.”

In a line, he froze.

“My mother’s been dead 20 years,” he said.

Minnie nodded.

“Mhm. Dead, but not gone. Some folks don’t go easy.”

She talked about that room, about what you did in here when you were a boy.

Henry’s grip on the chair tightened until his knuckles went white.

“You’re lying.”

She smiled toothlessly and sadly.

“You took her locket. The one with the picture of the river inside. She looked for it for days.”

The color drained from his face.

That memory—tiny childish theft—had never left his head.

He’d taken it from his mother’s dresser, hidden it in this very room. No one had seen. No one could have seen.

“How do you know that?” he whispered.

Minnie rose slowly from the chair, her back bent, but her presence somehow taller than his.

“The river tells me things, henhen. Things you forgot, things you tried to bury.”

He stepped back.

“You’re mad.”

“Maybe,” she said softly. “But madness remembers that night.”

Henry locked the nursery again.

He drank until the edges of the world blurred, and the sound of his name in her cracked voice stopped echoing in his ears.

When he finally slept, he dreamed of water. He stood by the riverbank near his childhood home—the one his mother had loved. The air smelled of rain and wild jasmine.

In the water’s reflection, he saw two figures: his mother and a small boy, barefoot and laughing.

She reached out to touch the boy’s cheek, but as her hand met the surface, the image rippled. The water darkened.

Then he saw another figure—a woman with gray hair and a crooked back, watching from the trees. When she smiled, the reflection of his mother began to fade, replaced by that same toothless grin.

Henry woke with a start, his sheets soaked in sweat.

The following morning, he found Minnie in the kitchen again, speaking quietly with the cook. The others fell silent when he entered.

“What were you saying to them?” he snapped.

“Just telling stories,” she said calmly.

“Lies, you mean?”

She tilted her head.

“Ain’t all stories got a bit of both?”

His hand shot out before he realized it. The slap echoed through the room. Minnie staggered back but did not fall. The cook gasped.

Henry’s voice broke with fury.

“You will never speak to me again unless I ask it. Do you understand?”

Minnie lifted her gaze, and in that moment, something ancient stirred in her eyes.

“You can hush a woman’s mouth, but not her knowing,” she said.

The next night, as he lay in bed beside his restless wife, the house began to creak.

The sound came from the hall—soft, dragging footsteps moving toward his door. He sat up, clutching the lamp. The footsteps stopped outside.

Then came a whisper—thin as breath through a keyhole.

“Henhen, you forgot to say your prayers again.”

The lamp went out.

Henry tore open the door, but the hallway was empty. Only the smell of damp river air drifted through the cracks in the old floorboards.

By morning, the servants claimed they’d heard the same thing—footsteps, whispers, laughter in the nursery. Minnie, however, was nowhere to be found.

Henry ordered the property searched from the cotton fields to the slave quarters.

They found her at last, sitting beneath the Magnolia tree near the edge of the swamp, her hands folded, her eyes closed, humming that same old tune.

When Henry demanded to know what she was doing, she looked up slowly and said, “Waiting for you to remember, child. Waiting for you to tell me where you buried her.”

He felt the world tilt beneath him.

“Buried who?”

But many only smiled, and the wind stirred her gray hair like mist.

“You know who,” she said. “The one who used to call you my sweet henhen.”

The blood drained from his face. He turned away, but her voice followed him. Soft and certain.

“Secrets don’t stay in the ground forever.”

For three days after Minnie’s words beneath the magnolia tree, Henry avoided her.

He convinced himself she was senile, delusional, perhaps playing tricks to gain sympathy. Yet her voice lived inside his mind like a seed that refused to die.

Where you buried her.

He tried to busy himself with plantation work—the cotton shipments were late, the overseer drunk again, and the accounts unbalanced.

But every time he dipped his pen into ink, he saw his reflection in the black surface of the bottle—his mother’s eyes staring back at him.

By the fourth night, sleep abandoned him entirely.

The mansion was too quiet. Even the usual songs from the slave quarters had gone silent, as though the air itself was listening.

When the clock struck midnight, Henry rose and lit a lamp.

He found himself walking toward the nursery again, his bare feet whispering against the wooden floor. The key trembled in his hand. The lock gave way with a sigh.

Inside, dust drifted like ghosts. The cradle still stood by the window, its fabric eaten by moths. The rocking chair moved slightly, though no breeze stirred.

Henry stepped inside. The boards groaned beneath him, remembering his weight from years ago.

Something compelled him toward the far wall, where the paint had peeled away in a faint circle. He knelt, setting down the lamp. With trembling hands, he pried at the loose boards.

The smell of soil rose up wet, old, familiar. His heart pounded. He reached inside and felt something cold, metallic. When he pulled it out, his breath caught in his throat.

The locket, tarnished now, its hinge stiff with age, but unmistakably his mother’s. The one he’d stolen as a boy.

He opened it carefully, expecting to see the miniature painting of the river.

But instead, there was something new inside—a lock of gray hair tied with a thin red thread and a small scrap of paper folded tight.

His hands shook as he opened it. The words were written in his mother’s delicate script.

For my Henry, the river takes what it is owed.

He staggered back, the lamp flickering wildly, the words blurred before his eyes.

The river, always the river.

The same place where his mother had vanished one stormy night when he was 12.

They’d called it an accident, though he’d never told anyone about the fight that came before.

How he’d shouted. How she’d fallen. How the current had taken her before he could reach her hand.

He pressed a hand to his mouth, choking on the taste of old guilt.

Then he heard it—a soft humming coming from behind him. He turned.

Minnie stood in the doorway, her silhouette haloed by the dim light of the hall. Her back was bent, but her presence filled the room like a storm.

“You found it,” she said.

Henry’s voice was a rasp.

“How?”

“How did you know?”

She walked closer, each step deliberate.

“Your mama comes to me by the river. She tells me what you forgot, what you hid. That locket’s been calling your name for years.”

He turned toward the window where the river shimmered in the distance like a silver scar.

When he looked back, Minnie was gone. Only the chair rocked slow and steady.

At dawn, the servants found Henry wandering down the path toward the riverbank, barefoot, still holding the locket.

He didn’t speak. He didn’t seem to see them. He knelt in the mud and stared at the water, whispering something they couldn’t hear.

Minnie stood behind him, silent, her eyes calm.

When the overseer approached her in fear, she said only one thing.

“The past don’t die. It just waits for someone brave enough to face it.”

And with that, she turned and walked back toward the house, humming that same lullaby—soft, endless, and heavy with the memory of a boy who had finally remembered his mother’s voice.

The morning after Henry knelt at the river, the entire plantation changed.

It wasn’t sudden, not like a storm that bursts open the sky, but slow, quiet, and heavy, as though the earth itself was holding its breath. The air smelled of wet iron.

The crows refused to land on the fences. Even the slaves in the field spoke in hushed tones when they caught sight of the house.

Something had shifted. The balance had tipped.

Henry Lockheart was no longer the same man.

He came back from the river soaked to the bone, his boots caked with mud, his eyes distant and hollow. When the overseer tried to speak to him, Henry only said, “The river doesn’t forget.”

Then he locked himself in his study and didn’t come out for two days.

By the third morning, Minnie appeared at the door with a tray of food. She knocked once. No answer. Again, nothing. She pushed the door open.

Henry sat by the window, staring at the horizon. His mother’s locket hung from his neck. The papers on his desk were soaked with spilled ink, the words bleeding into one another.

“You should eat something,” Minnie said softly.

He didn’t turn. “I keep hearing her voice.”

Minnie set the tray down, her hands steady. “That’s because you ain’t done listening yet.”

Henry turned slowly, his face pale, his eyes rimmed red. “She forgave me. Didn’t she?”

“That ain’t for me to say,” Minnie replied. “Forgiveness is between you and the river.”

He laughed once, a sound like cracking wood. “The river?”

“It spoke to me,” he whispered. “It said, ‘There’s a debt still unpaid.’”

Minnie’s expression didn’t change. “Then you best find what’s owed.”

That night, a storm gathered.

The sky turned a deep, bruised purple, lightning flickering far beyond the fields.

The slaves huddled in their quarters, whispering of curses and restless ghosts. They said the master’s house was haunted—not by one spirit, but by all those the Lockharts had wronged.

Inside, Henry paced the halls like a man possessed.

The rain hammered the windows, the wind howled through the cracks, and every door seemed to groan his name. He found himself standing once again before the locked nursery.

The key still hung from his pocket. He hesitated, then turned it slowly.

News

The Mother and Daughter Who Shared The Same Slave Lover… Until One of Them Disappeared

The Rosewood Curse: A Love Written in Fire In the sweltering heat of August 1842, the Rosewood plantation lay bathed…

Tennessee 2003 Cold Case Solved — arrest shocks community

The sun was beginning to dip beneath the horizon on the last weekend of July 2003, casting an amber glow…

13-Year-Old Sold to 51-Year-Old Plantation Owner… 8 Years Later, She Was His Worst Nightmare

The Hartwell Massacre: The Story of Rebecca’s Revenge and the Price of Justice The iron gate of the kennel yard…

A young Black girl was dragged into the kennel to be humiliated, left before 10 hunting dogs — but…

The Silent Bond: Naomi and Brutus’ Fight for Survival The iron gate of the kennel yard swung open with a…

Silas the Silent: The Slave Who Castrated 8 Masters Who Used Him

The Silent Revenge: The Story of Silas the Silent In the heart of South Carolina’s low country, the year 1836…

The Alabama Twin Sisters Who Shared One Male Slave Between Them… Until They Both Got Pregnant

The Dark Legacy of Bell River Plantation: Secrets, Lies, and Betrayal In the small, rolling hills of Henrico County, Virginia,…

End of content

No more pages to load