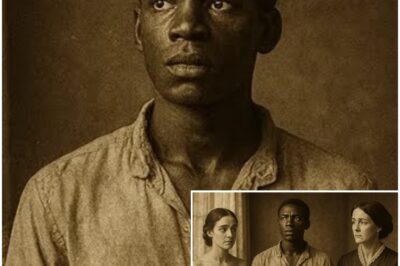

The Impossible Longevity of Caesar Bowen: A Mystery Shrouded in Time

The year was 1888, and Green County, Ohio, was no stranger to its fair share of local legends and stories, but nothing would rival the tale of Caesar Bowen.

A man whose documented age of 126 years—listed in official death records—stunned not only the medical community but also the entire town.

For over a century, this case had been quietly tucked away in county archives, with an unsettling truth that remained buried beneath layers of bureaucracy and suspicion.

The question was simple yet profound: how could someone live for so long? How could a man survive for over a century when the oldest verified person, according to medical records, lived only to 108?

But it wasn’t just the age that baffled everyone. It was Caesar’s life, his history, and the mysterious circumstances surrounding his extraordinary existence that left everyone around him questioning the very nature of human capability.

A truth that, once uncovered, threatened to dismantle the foundation of everything the community believed to be possible. What did they discover in his cabin after his death? And what were the terrifying implications of Caesar Bowen’s life that the authorities worked tirelessly to suppress?

Let me take you back to where it all began—the story of Caesar Bowen, a man whose longevity was just the tip of an even darker mystery.

In the 1880s, Green County, Ohio, was a quiet and modest farming community. The railroad had brought in new commerce, but the past of the region still loomed heavily in the form of the local legends, particularly those surrounding its older residents.

Caesar Bowen was one such resident. He lived on the outskirts of the town in a small, weathered cabin that had been there for at least 60 years—some said much longer.

The logs of the cabin were darkened with age, the chimney leaned at an angle that seemed almost impossible, and the roof was held down by stones, a construction method that hadn’t been seen since the 1810s.

Caesar was a familiar sight in town. He stood barely 5 feet tall, his body bent and gnarled from age, his movements slow and deliberate.

Yet, despite his frailty, there was something about his presence that made people uneasy. His skin had the texture of old leather, deep creases etched into his face like rivers on a map, but his eyes—his eyes were the most unsettling.

They were a pale brown, like creek water over sand, and they would fix on you with an intensity that made even the toughest of men look away.

Dr. Harold Sutton, the town physician, had been trying to examine Caesar properly for years, but the old man refused every offer of medical assistance, insisting that no doctor had ever done him good. “And I suspect none ever will,” he would say.

Despite this, Dr. Sutton couldn’t ignore Caesar’s remarkable vitality for a man of his supposed age.

“His pulse is barely 40 beats per minute,” Dr. Sutton confided to his wife, Margaret, one evening over dinner. “His respiratory rate suggests deep sleep, yet he is fully conscious.

I’ve read every medical text available, but there is no precedent for this. If he’s truly 126, he should have died decades ago.”

The records supported Dr. Sutton’s claims. The county manumission document dated July 4, 1826, listed Caesar as a man of about 64 years.

He had been freed from the service of one Jeremiah Hawthorne of Virginia, after being in the family since 1784.

Working backward, even the most conservative estimates placed Caesar’s birth somewhere around 1762, during the reign of King George III when Ohio was still considered an unmapped wilderness.

But it was Caesar’s testimony, recorded by local historians and published interviews, that painted a picture far more extraordinary than anyone could have anticipated.

In 1885, he granted an extensive interview to a young reporter named Thomas Fletcher from the Zenia Gazette.

The interview, meant to be a short human-interest piece about the oldest resident of Green County, quickly became a gripping account of a life that spanned not only decades, but centuries.

“I was born on a tobacco farm in Tidewater, Virginia,” Caesar began, his voice raspy but clear. “My mother was 16, and she died that same year. Fever took her.

My father, I never knew. He was sold away before I could walk. The master’s name was Josiah Warren, and he worked 200 acres with 23 souls. I was the smallest, the weakest. They didn’t think I’d live past my first winter.”

Fletcher, expecting a few colorful stories for his column, found himself writing non-stop for hours, his hand cramping as Caesar spoke of the events he had witnessed in his long life.

When Fletcher asked him about the changes he’d seen in America, the country’s expansion, and the rising tension that would soon lead to the Civil War, Caesar’s answers were both chilling and fascinating.

He spoke of the Stamp Act riots, of the French influence in Ohio Valley before the Revolution, and even of winters so cold that trees exploded from the frost.

“I remember the first time I heard of the Revolution,” Caesar continued in his interview, his voice carrying a strange weight. “I was just a boy, no older than 8, when Pontiac’s rebellion took place.

The French still had influence here, and I remember the fear of the settlers, the whispers of war on the wind.”

Fletcher had expected stories of hardship, of enslavement, but Caesar’s recollections went beyond that. “I remember the burning of Washington in 1814,” Caesar said, his voice gaining a faraway quality.

“I was in the field when I heard. Tobacco plants tall enough to hide a man. The overseer came running, shouting that the British had taken the capital, that they had burned it to the ground.

I remember thinking, ‘This is what empires do to each other. They destroy the symbols of power. But they forget that the real power lies in the people who plant the tobacco, who build the buildings, who create the wealth that makes the symbols possible in the first place.’”

Dr. Sutton had been fascinated by the interview, but as time went on, he began to notice something even more perplexing.

Caesar’s health was deteriorating rapidly, and yet his memory remained disturbingly sharp. In fact, the more Dr. Sutton examined him, the more he realized that Caesar wasn’t just remembering his own life—he was remembering things that didn’t belong to him.

In October of 1887, Caesar stopped speaking altogether. One afternoon, as Samuel Pritchard, a neighbor, arrived at Caesar’s cabin to check on him, he found the old man sitting motionless, staring at the wall.

Caesar looked at him, opened his mouth to speak, but no sound came out. The expression on his face was one of recognition, of horror, as if he’d suddenly realized something terrifying.

Samuel rushed forward to help, but Caesar pushed him away with surprising strength. Then, with a look that seemed to carry an entire lifetime of grief, Caesar pointed to the door, indicating that he wanted to be left alone.

Over the next few weeks, Caesar’s condition worsened. He couldn’t speak, his appetite waned, and his physical health seemed to disintegrate.

Dr. Sutton tried to understand, but the old man’s body simply refused to follow the laws of biology.

Even in his frailty, Caesar would sometimes mutter things that made no sense—names, places, events that shouldn’t have been part of his life.

On January 5th, 1888, Caesar awoke from what seemed like a deep sleep, and after months of silence, he spoke his first words: “How many years has it been?”

“Since what?” Dr. Sutton asked gently.

“Since I was young,” Caesar whispered.

Dr. Sutton’s heart raced. He knew something was terribly wrong. “What crossing?” he asked, as Caesar’s voice faltered.

“The middle passage,” Caesar replied, his voice distant, his eyes clouded with some memory that wasn’t his. “But I was born here. Born in Virginia.”

Dr. Sutton froze. What was happening to this man? How could he speak of something he could not have possibly experienced? Yet, there was a depth in Caesar’s eyes that suggested a truth far beyond any rational explanation.

“I remember the smell of tobacco leaves drying in the barn,” Caesar continued in a whisper. “The way the light came through the cracks in the walls. The sound of the songs from Africa, those songs none of us remembered the meaning of, but we sang them anyway.

Because our mothers sang them, and their mothers before them. But I also remember being hungry. Always hungry.”

As the days passed, Caesar’s condition continued to decline. He slipped into a feverish delirium, calling out names that made no sense—Abigail, Jonas, Cypio, Delilah, Samuel.

“Tell them I tried,” he muttered one night, his eyes wide open but unseeing. “Tell them it was never supposed to be this long.”

By February 1888, Caesar’s decline was unmistakable. He could no longer sit up on his own. But as his physical strength diminished, his mind seemed to awaken in new ways, revealing memories that seemed impossible.

He began speaking in languages that no one could identify—strange, ancient dialects, rhythms of sounds that seemed both foreign and familiar. “They’re here,” Caesar whispered one evening, his voice trembling with urgency.

“Every person whose story I’ve carried. They’re all here now, pressing in on me, demanding their time back.”

As the days turned into weeks, the once-strong man’s body grew frail. The townspeople, who had long been fascinated by Caesar, began to speak of him as something more than just an old man.

Some said he wasn’t just living a long life—he was living the lives of others, carrying their memories, their pain, and their joy.

On the morning of May 5th, 1888, Caesar awoke for the last time. He was quiet and calm, his breathing shallow but steady. “I’m ready now,” he said, his voice barely audible. “I’ve carried enough.”

At 2:47 p.m. that day, Caesar Bowen took his final breath. His passing was quiet, a soft exhalation of a life that had spanned more years than any human should have lived.

But what Caesar left behind—his journals, his memories, and the impossible span of his life—left more questions than answers. His death was the beginning of a new mystery.

How could one man live for 126 years? How could he carry the memories of others? Was it possible that Caesar had lived through the lives of countless souls, witnessing their suffering and joy?

Theories ranged from scientific to supernatural, but one thing was certain: Caesar Bowen was not just a man. He was a witness, a living archive of experiences, and a testament to something far beyond human comprehension.

News

The Mother and Daughter Who Shared The Same Slave Lover… Until One of Them Disappeared

The Rosewood Curse: A Love Written in Fire In the sweltering heat of August 1842, the Rosewood plantation lay bathed…

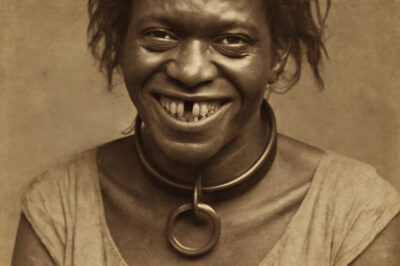

The Master Bought a Toothless Slave To Amuse His Guests…Then She Called Him by His Childhood Name

The Debt of the River: A Legacy of Ashes In the spring of 1853, on the outskirts of Natchez, Mississippi,…

Tennessee 2003 Cold Case Solved — arrest shocks community

The sun was beginning to dip beneath the horizon on the last weekend of July 2003, casting an amber glow…

13-Year-Old Sold to 51-Year-Old Plantation Owner… 8 Years Later, She Was His Worst Nightmare

The Hartwell Massacre: The Story of Rebecca’s Revenge and the Price of Justice The iron gate of the kennel yard…

A young Black girl was dragged into the kennel to be humiliated, left before 10 hunting dogs — but…

The Silent Bond: Naomi and Brutus’ Fight for Survival The iron gate of the kennel yard swung open with a…

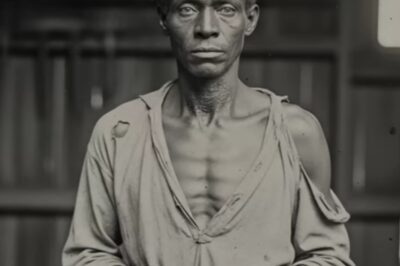

Silas the Silent: The Slave Who Castrated 8 Masters Who Used Him

The Silent Revenge: The Story of Silas the Silent In the heart of South Carolina’s low country, the year 1836…

End of content

No more pages to load