In the summer of 1976, a story emerged that shook the quiet, isolated backwoods of eastern Kentucky to its core.

It began with a visit to a property known as the Fowler farm, a place that had been shrouded in mystery and fear for generations.

The Fowlers had lived there since before the Civil War, some say longer, and their presence was as much a part of the land as the trees and hills that surrounded it.

It was a family that had remained almost entirely apart from the world. They were known only by whispers—people who lived in the woods, who spoke in strange dialects, who never came to town for supplies.

It wasn’t that the Fowlers were feared exactly; it was more that they were avoided.

In Harland, the nearest town about 17 miles down a muddy, winding road, folks knew about the Fowlers the way you know about a wasp nest in your attic.

You don’t go looking. You don’t ask questions. You just accept that some things are better left alone.

But in 1976, Margaret Vance, a social worker with a quiet but relentless determination, couldn’t leave it alone anymore. She had heard rumors of children living on the Fowler property—children who had never seen a doctor, never attended school, and had no known birth certificates.

There were other rumors, darker and stranger, whispers about lights in the woods at night and sounds that didn’t quite match anything natural.

Margaret had heard it all before, but something in her wouldn’t let it go. She couldn’t shake the feeling that there was more to this story, something that had to be uncovered, no matter how strange it seemed. So, on a Tuesday morning in June, she made the decision to visit the property herself.

The journey up to the Fowler farm wasn’t an easy one. The road quickly turned from dirt to a path barely wide enough for a car to pass through.

Margaret had to abandon her car half a mile down and walk the rest of the way, her boots crunching in the dense underbrush. The woods grew so thick that the sunlight barely touched the ground.

The further she went, the quieter it became. No birds. No insects. Just the sound of her own breathing and the occasional snap of twigs underfoot.

It was a silence that made the hairs on the back of her neck stand up, an unnatural kind of quiet that felt like it had been there for years.

When she finally reached the clearing, Margaret saw the structure that had once been a house. It looked as though it had been built and rebuilt over generations, rooms added without any real sense of order.

The wood was rotting, the windows covered with tar paper and cloth. A smell filled the air, something organic and wrong, like meat left too long in the heat. Margaret didn’t hesitate; she called out to anyone inside, but there was no response.

She called again, louder this time, her voice breaking the heavy silence, but it was then that she heard something that made her blood run cold.

It wasn’t the creak of a floorboard or the sound of someone shifting in the shadows. No, it was the unmistakable sound of children’s voices—but not speaking any language Margaret recognized.

Not English, not any native dialect she’d ever heard. It was something older, something made up, something unnatural. The sound felt alien, like it shouldn’t exist at all.

Margaret moved to the back of the house, where she found a small, weathered door—so worn that it seemed almost part of the earth itself. She opened it and descended into the dark.

The root cellar was unlike any she had ever seen. It went down deeper than any root cellar should, the walls made of stacked stone and clay. It was dim, but enough light filtered through cracks in the floorboards above for her to see what lay at the bottom.

Three children. Two girls and a boy, all of them somewhere between the ages of 8 and 12, though their exact ages would never be determined with certainty.

They were pale in a way that went beyond a lack of sunlight. Their skin had an almost translucent quality, the blue veins beneath visible like rivers on a map.

Their eyes—those eyes—were too large, reflecting light like an animal’s eyes caught in the beam of a flashlight. They didn’t cry when they saw her.

They didn’t run. They simply stared at her, with an expression of recognition, as though they had been expecting her, as though they knew someone would come.

The children were dressed in clothes that looked hastily made—stitching rough, the fabric a mix of flower sacks or old curtains, stained with dirt and something darker.

Their hair was short, almost shaved. As Margaret moved closer, she noticed something strange—markings on their scalps. They weren’t scars exactly, but symbols, burned or carved into the skin. They were circles within circles, lines branching like tree roots or veins.

“Who are you?” Margaret asked, her voice soft but laced with fear. The oldest girl opened her mouth to speak, but what came out wasn’t a word. It was something between a hum and a whisper that made Margaret’s teeth ache.

“Where are your parents?” Margaret asked next, trying to hold back the growing sense of dread.

The boy, his large eyes never leaving her, pointed upward, toward the house.

Then, without a word, he pointed downward, to the earth beneath their feet. Margaret’s stomach churned as she realized the meaning. She didn’t want to know.

Trembling, she radioed for backup. Within hours, the property was swarming with law enforcement—county sheriffs, state police, and two men in unmarked suits who took control the moment they arrived.

The children were removed from the property that same day, wrapped in blankets, carried away to waiting vehicles, while police combed through the Fowler house, searching for answers.

What they found was worse than anyone could have anticipated. The house had been abandoned for years, but it hadn’t just been left.

The food in the cupboards had rotted to powder, and the furniture was arranged in strange configurations—chairs facing walls, tables overturned, beds torn apart with mattresses shredded and scattered.

In what could have been a kitchen, investigators found hundreds of jars lined up on shelves.

Some contained organs—deer hearts, rabbit kidneys—but there were others, organs that defied classification.

Medical examiners noted the presence of “unknown mammalian tissue” and “cellular structure inconsistent with regional fauna.” But it wasn’t just the jars that disturbed them.

In a room in the back of the house, a door had been nailed shut from the outside. When it was finally opened, investigators were met with a sight so grotesque that it made two officers request immediate transfers.

The walls of the room were covered from floor to ceiling with writing.

Not English, not any alphabet they could recognize. The symbols, too, matched the ones on the children’s scalps.

Mixed among the symbols were crude, disturbing drawings—figures that looked almost human, but with too many joints, too many fingers, eyes that were placed too far apart.

In the center of the room, there was a table. Leather straps, worn smooth from use, were stained with substances that, when tested, were found to be human blood—three different types, all matching the blood types of the children.

The two men in unmarked suits took photographs of everything and then ordered the room sealed.

By the morning, those photographs had disappeared from the evidence storage, and the two officers who had been in the room first were told they’d seen nothing worth remembering.

The children were taken to a facility in Lexington, a place that wasn’t listed on any public records, but had been used before for cases the government wanted to keep quiet.

They were separated immediately and placed in different wings, examined by doctors who had signed non-disclosure agreements before being allowed anywhere near the children.

The initial reports came back with disturbing results. The children’s bone density was wrong. Their internal temperature ran lower than the normal human baseline, and their heart rates indicated severe bradycardia.

Yet they showed no signs of distress. Blood work revealed abnormalities, and Dr. Raymond Hol, the examining physician, wrote in his notes that the case required immediate consultation with geneticists.

But before consultations could take place, the lab technician working with the samples, Patricia Gomes, flagged the results. What she saw, what she couldn’t explain, would change everything.

When the children’s blood was tested against the human genome, it didn’t match. There were markers that didn’t belong to any known human haplogroup.

The blood didn’t fit into any human lineage. The chromosomes were correct, but the banding patterns were wrong.

Patricia ran the tests again. And again. And again. Each time, the results were the same. The genetic markers didn’t match anything in the human genome database.

When Patricia called her supervisor, the situation quickly escalated. Within hours, two federal agents arrived, taking all of Patricia’s work and demanding that she never speak of what she had seen.

She was told the case was classified. And two days later, Patricia resigned from her position, never discussing what she had witnessed.

The children were removed from the facility within 72 hours of their DNA results being flagged. Their files, like everything else related to the Fowler case, were sealed.

The children’s whereabouts after they left the facility were classified.

Margaret Vance, the social worker who had discovered them, tried to follow up, but when she demanded answers, she was told the children had been placed with specialized foster families, and that any further questions would be considered an obstruction of a federal investigation.

Margaret never spoke about it again. She kept a hidden file filled with copies of documents she had managed to acquire before everything was sealed.

In 2009, after Margaret’s death, her daughter found a key to a safety deposit box in her mother’s belongings.

Inside that box was a single sheet of paper with three names written on it—and a note that read: “They weren’t human. Not completely. Someone knew before they were ever found.”

And so, the mystery of the Fowler children was buried, hidden behind layers of bureaucratic red tape and government secrecy. The Fowler property, once the site of unimaginable horrors, was burned to the ground, the land reclaimed by the forest.

But the truth remained—somewhere in the shadows, buried in forgotten archives, whispered by those who dared to speak of it.

The question was never if the truth would surface. It was whether we were ready to face it.

News

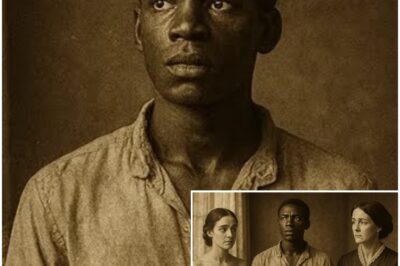

The Mother and Daughter Who Shared The Same Slave Lover… Until One of Them Disappeared

The Rosewood Curse: A Love Written in Fire In the sweltering heat of August 1842, the Rosewood plantation lay bathed…

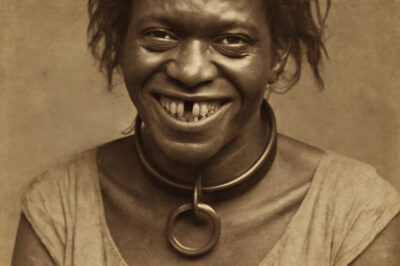

The Master Bought a Toothless Slave To Amuse His Guests…Then She Called Him by His Childhood Name

The Debt of the River: A Legacy of Ashes In the spring of 1853, on the outskirts of Natchez, Mississippi,…

Tennessee 2003 Cold Case Solved — arrest shocks community

The sun was beginning to dip beneath the horizon on the last weekend of July 2003, casting an amber glow…

13-Year-Old Sold to 51-Year-Old Plantation Owner… 8 Years Later, She Was His Worst Nightmare

The Hartwell Massacre: The Story of Rebecca’s Revenge and the Price of Justice The iron gate of the kennel yard…

A young Black girl was dragged into the kennel to be humiliated, left before 10 hunting dogs — but…

The Silent Bond: Naomi and Brutus’ Fight for Survival The iron gate of the kennel yard swung open with a…

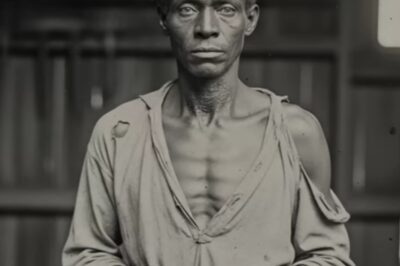

Silas the Silent: The Slave Who Castrated 8 Masters Who Used Him

The Silent Revenge: The Story of Silas the Silent In the heart of South Carolina’s low country, the year 1836…

End of content

No more pages to load