In the suffocating autumn of 1859, in the isolated village of Meow Creek, Louisiana, the world was about to bear witness to a mystery that would shatter the boundaries of human understanding.

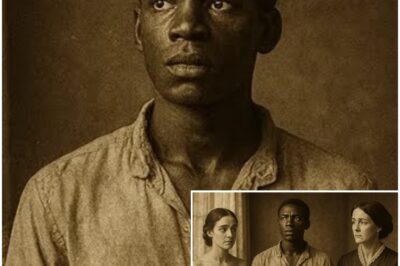

It was the story of a 7-year-old black boy named Samuel Carter, whose abilities defied every known law of nature, and whose mere existence unsettled the world around him.

Dr. Elizabeth Monroe, the only formally trained physician in the region, began documenting Samuel’s case, filling two leather-bound journals with her observations.

At first glance, Samuel appeared to be nothing more than an ordinary child—small, frail, with dark eyes that rarely blinked and skin the color of rich Mississippi soil.

But there was something in his eyes, something that hinted at a knowledge beyond his years. Something that terrified those who came into contact with him.

“I hear them,” Samuel would whisper, his voice calm yet unnerving. “The voices from the swamp… they tell me things… things about people… things about their deaths.”

The boy’s words seemed like the ramblings of a child’s imagination. Yet, over the course of seven long and terrifying months, nine people died after interacting with Samuel.

All were found with their eyes wide open, their faces frozen in expressions of pure terror—as though they had seen something beyond human comprehension.

The local authorities dismissed these deaths as natural occurrences, but Dr. Monroe’s journals, which would survive the ravages of time, painted a very different picture. Samuel Carter was no ordinary child.

Samuel was born in the spring of 1852 on the Witmore plantation, one of the largest cotton operations in Ascension Parish.

His mother, Esther Carter, was a house servant who had learned to read despite the laws forbidding literacy among enslaved people.

She would trace letters in the dirt behind the kitchen house, teaching her son in stolen moments.

“Look, Samuel,” she would say softly, glancing over her shoulder to make sure no one was watching, “these are letters. They’re how we speak without saying words.”

Samuel would repeat the letters in the dirt, his small fingers tracing them with the kind of concentration that belied his age. “I can read, Mama,” he’d say, a quiet pride in his voice. “I know what they mean.”

Esther’s love for her son was profound, but it was also overshadowed by the harsh realities of plantation life.

Samuel’s father, whose name was never recorded in any official document, had been sold away before Samuel’s second birthday.

Esther rarely spoke of him, though sometimes, Samuel would wake in the middle of the night to find his mother sitting by the window, tears streaking her face as she stared into the darkness.

When Samuel was four years old, Esther developed a persistent cough that refused to go away. Despite her deteriorating condition, Robert Whitmore, the plantation owner, refused to call a doctor for a slave.

He insisted that Esther continue with her duties, no matter how ill she became. Samuel, unable to comprehend the cruelty of his circumstances, sat beside his mother at night, holding her hand, and whispered things that frightened her.

“Mama,” Samuel said one night, his voice unusually heavy for a child, “the sickness is like a flower growing inside you. It has roots that spread. The voices from the swamp say it will take you before the cotton blooms again.”

Three months later, in February of 1856, Esther died, coughing blood into rags that Samuel tried desperately to keep clean. At just four years old, Samuel did not cry at her funeral.

He stood silent as the other enslaved people sang spirituals over her grave, located in a corner of the plantation where black bodies were buried without markers.

When asked why he didn’t weep, Samuel simply said, “She’s still here. She talks to me now, like the others in the swamp. She says she’s finally free.”

The other enslaved people on the Witmore plantation began to fear Samuel. “There’s something in his eyes,” they whispered. “Something old, something that knows too much for a child his age.”

Old Jeremiah, who had worked the plantation longer than anyone could remember, spoke to the others with a quiet seriousness. “That boy got the sight. He knows things he ain’t supposed to know. Things about the dead.”

Even Robert Whitmore, who was accustomed to the strange and often unsettling world of his enslaved workforce, could not ignore Samuel.

The boy was too smart, too articulate, too perceptive for a child who had never been formally educated.

When Samuel was five, Whitmore found him drawing in the dirt—not childish scribbles, but detailed anatomical sketches of the human heart, with labels written in careful script.

“Where did you learn to write, boy?” Whitmore demanded, his voice sharp with suspicion.

Samuel looked up at him with those unblinking eyes. “The voices teach me. They show me things in my mind. They say the body is just a house, and when the house breaks, the person inside has to leave.”

Whitmore, deeply unsettled, didn’t know what to make of the child.

The idea that a black child—especially one born into slavery—could possess knowledge and intelligence beyond his own understanding was terrifying.

Samuel, in that moment, represented a direct threat to everything Whitmore and others like him had built their world on. If a child like Samuel could possess such brilliance, what did that say about the system of slavery, built on the idea that black people were inferior?

In the summer of 1856, when Samuel was only four and a half years old, Robert Whitmore made a decision that would change the boy’s life forever.

He sold Samuel to a passing slave trader, getting rid of the child who made him uncomfortable, the child who challenged everything he believed about race and intelligence.

Samuel was taken from the only home he had ever known, separated from the community that had raised him after his mother’s death, and transported along the Mississippi River.

But Samuel never made it to auction. During a stop in Maro Creek, the slave trader, Cyrus Blackwood, suddenly fell ill with violent convulsions.

He died within hours, blood pouring from his nose and ears, his body wracked with seizures that the local doctor couldn’t explain.

Samuel, who had been standing in the corner of the room watching quietly, said only, “He hurt children. The voices told me what he did. They said his time was finished.”

An investigation into Blackwood’s background revealed a disturbing pattern. Over the past five years, several enslaved children in his custody had died under mysterious circumstances.

Samuel had somehow known things about Blackwood that no one had ever investigated. Secrets that died with the trader in that boarding house room.

With no one to claim Samuel, no legal guardian willing to take responsibility for a slave child, the boy found himself in an unprecedented situation—technically free, though freedom meant little for a black child in Louisiana in 1856.

Dr. Elizabeth Monroe, intrigued by the strange black child who had been present when Blackwood died, took Samuel into her home.

Dr. Monroe, a rarity in antebellum Louisiana, was one of the few women to study medicine in Philadelphia and return to practice in the South despite the social stigma she faced.

She had inherited property from her father and used her independence to live according to her own principles, including a quiet but firm opposition to slavery.

When Samuel first met Dr. Monroe, she asked him his name. “Samuel Carter,” the boy said, looking up at her with those intense, knowing eyes.

“My mama named me Samuel because it means God has heard. She said I was born to hear things that others couldn’t hear, to know things that others didn’t know.

The voices started talking to me before I could talk back to them.”

Dr. Monroe, though trained in the rational methods of scientific medicine, could not dismiss the strange boy before her.

He spoke with clarity and precision that should have been impossible for an illiterate child. He described the inner workings of the human body with perfect accuracy, even though he had never seen an anatomy book.

And when he talked about the voices, he spoke with a calmness that suggested he had lived with them for a long time.

“I want to understand how your mind works,” Dr. Monroe said, “but I will not treat you as a specimen or a curiosity.

You will be treated with dignity and respect. If at any time you wish to leave, I will help you find another situation.”

Samuel looked at her thoughtfully and then replied, “The voices say you see people as people, not property or problems.

They say you’re trying to understand things that scare most folks.

I’ll stay with you, Dr. Monroe. But you need to know something. The people who come near me, who mean harm, or who carry darkness in their hearts… they don’t live very long.

I don’t kill them. I just know when death is coming for them, and sometimes the voices make sure it happens faster than it would have otherwise.”

Despite her discomfort with the boy’s words, Dr. Monroe was captivated by him.

He wasn’t just extraordinary in his intelligence—he was something else, something beyond her understanding.

She agreed to take him in as a medical subject, offering him food, shelter, and education in exchange for his cooperation in helping her understand his extraordinary abilities.

Over the following months, Dr. Monroe documented Samuel’s abilities.

He predicted deaths with chilling accuracy, exposed hidden truths about people’s lives, and revealed secrets that no one had known.

Samuel’s knowledge seemed to come from somewhere beyond this world—somewhere deep and dark, like the voices from the swamp he spoke of. He wasn’t just a child with exceptional intelligence; he was something more.

But as the months passed, Samuel began to question the nature of his gifts. What if he was wrong about everything? What if the voices weren’t divine, or ancestral, or even real?

What if they were just the product of his grief, his anger, his desire for justice in a world that had done so much harm to him and his people?

These were the questions that haunted him, even as the voices continued to guide him, telling him things he could never have learned through ordinary means.

As time went on, Samuel’s role in Maro Creek became more ominous. People began to fear him. The white community whispered that he was cursed, that he brought death wherever he went.

But among the enslaved people, he became something of a legend. Some believed Samuel was a prophet. Others thought he was the embodiment of a powerful spirit from the past. But all agreed that he was no ordinary child.

In the end, Samuel Carter’s story became one of mystery, legend, and tragedy. A boy with gifts that terrified the very people who had created the system of oppression.

A boy whose existence forced society to confront uncomfortable truths about intelligence, power, and humanity.

And though his story faded into the shadows of history, the memory of Samuel Carter lived on—his voice still echoing through the swamp, still carrying the weight of all the suffering, injustice, and hope that had been buried by time.

News

The Mother and Daughter Who Shared The Same Slave Lover… Until One of Them Disappeared

The Rosewood Curse: A Love Written in Fire In the sweltering heat of August 1842, the Rosewood plantation lay bathed…

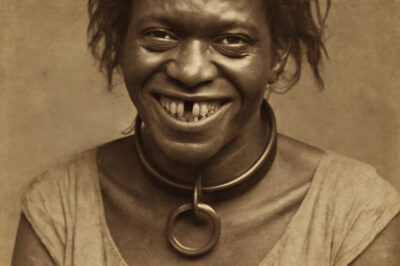

The Master Bought a Toothless Slave To Amuse His Guests…Then She Called Him by His Childhood Name

The Debt of the River: A Legacy of Ashes In the spring of 1853, on the outskirts of Natchez, Mississippi,…

Tennessee 2003 Cold Case Solved — arrest shocks community

The sun was beginning to dip beneath the horizon on the last weekend of July 2003, casting an amber glow…

13-Year-Old Sold to 51-Year-Old Plantation Owner… 8 Years Later, She Was His Worst Nightmare

The Hartwell Massacre: The Story of Rebecca’s Revenge and the Price of Justice The iron gate of the kennel yard…

A young Black girl was dragged into the kennel to be humiliated, left before 10 hunting dogs — but…

The Silent Bond: Naomi and Brutus’ Fight for Survival The iron gate of the kennel yard swung open with a…

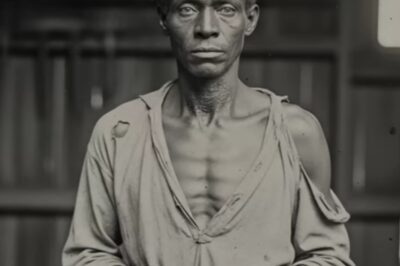

Silas the Silent: The Slave Who Castrated 8 Masters Who Used Him

The Silent Revenge: The Story of Silas the Silent In the heart of South Carolina’s low country, the year 1836…

End of content

No more pages to load