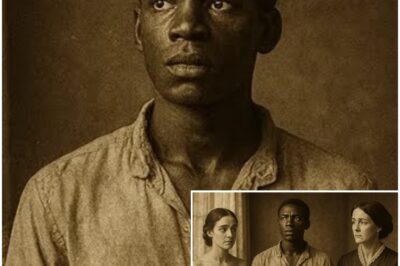

The Impossible Resistance: The Story of Jacob Terrell

It was the spring of 1856, a time when the plantation system in the American South ran with brutal efficiency.

In the rolling hills of northeastern Alabama, where the Talapusa River sliced through red clay and tall pines, Harrington Plantation stood as a monument to the old ways.

Founded by Colonel Marcus Harrington, a former veteran of the Creek War, the plantation spanned over 3,000 acres.

By 1856, it was one of the wealthiest and most productive operations in Madison County, with over 240 enslaved individuals working the land, producing 1,500 bales of cotton each year.

Colonel Harrington was known for his strict discipline and meticulous attention to detail. His plantation was one of the few in the region that ran with what could only be described as mathematical precision.

Every detail was tracked, from the amount of cotton picked to the hours worked and, of course, the punishments administered. Punishment on the plantation was as much a part of the daily routine as planting and harvesting.

The system ran smoothly because fear was its engine, and Colonel Harrington kept that engine well-oiled.

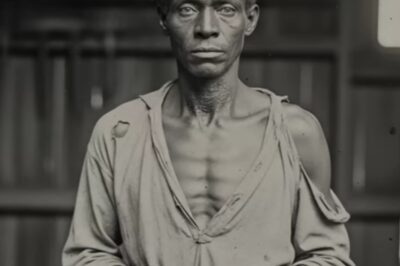

Jacob Terrell had been brought to Harrington Plantation in 1852, purchased at an auction in Richmond for an extraordinary sum—$2,000, nearly three times the average price for an enslaved person.

The records from the auction house described him as a man of remarkable physical strength: 6’7″, 260 pounds, with a background in industrial labor, particularly in iron foundries and timber operations.

He had the body of a laborer forged in the fires of a furnace, a kind of strength that was built for hard, physical work rather than the lean endurance of typical field hands.

But it wasn’t just his strength that had drawn Colonel Harrington’s eye. Jacob’s size, his calm demeanor, and his apparent willingness to follow orders had made him an ideal candidate for the most demanding tasks on the plantation.

For nearly four years, Jacob performed his duties with quiet efficiency.

He never questioned orders, never resisted the overseers. He worked without complaint, moving logs, operating the cotton press, and managing the heaviest equipment.

But something changed in the winter of 1855. A letter arrived for Jacob. Letters for enslaved people were strictly forbidden, but somehow one had reached him, its contents unknown.

Martha Clemens, the head cook at the plantation, later recalled seeing Jacob standing behind the cookhouse one cold October evening, holding the letter in his hands.

His face, she said, was “like a man who realized he was already dead.” That moment, she remembered, was the turning point.

From that night on, Martha noticed a shift in Jacob. He still worked with the same mechanical precision, but there was something different about him.

He asked questions about the boundaries of the plantation, the distances to nearby towns, and the depth of the Talapusa River. Subtle changes in his behavior made the overseers uneasy.

Thomas Gibbard, the head overseer, began taking note of Jacob’s odd behavior in his daily log.

“He’s been asking questions about distances and water sources,” Gibbard wrote. “His compliance is too perfect, and I don’t like it.”

Over the next several months, Jacob became a mystery. The other enslaved people began to notice that something was off.

Some of them avoided him, while others gravitated toward him, drawn to his stillness, his quiet confidence. He didn’t speak much, but when he did, his words seemed heavy, as though he carried a knowledge they couldn’t understand.

Old Samuel, who had worked on the plantation longer than anyone, once told Martha that Jacob reminded him of the calm before a storm, the eerie silence that descended before the tornado struck. “He ain’t right,” Samuel said. “He’s different now. It’s like he’s waiting for something, but I don’t know what.”

By the time March 1856 arrived, things had changed in a way no one could have anticipated.

Colonel Harrington, preoccupied with the upcoming wedding of his daughter Caroline to a Charleston merchant, ordered an expansion of the cotton press operation.

New equipment needed to be installed, and additional land needed to be cleared. Jacob was tasked with leading this project.

It was on the morning of March 14th, 1856, when everything would come to a head. The day started like any other—fog from the Talapusa River rolled in, thick and cold, muffling the sounds of the plantation.

The bell rang at 5:30 a.m., and Jacob reported to the cotton press area along with eight other men, ready to clear land for the new equipment.

The overseers—Gibbard, Eli Strauss, and William Pritchard—were there as well, each armed with their usual tools of control: leather straps, wooden bats, and Gibbard’s pistol.

By 7:15 a.m., Gibbard approached Jacob with a leather strap in hand.

“Move that beam, Terrell,” Gibbard ordered, his voice sharp.

Jacob didn’t respond.

“Move it,” Gibbard repeated, stepping closer to him. “Now.”

Jacob remained still. He didn’t flinch, didn’t even look at Gibbard. His eyes were fixed on the fog, his body rigid as though frozen in place.

“I said move!” Gibbard snapped, raising the strap to strike Jacob’s back.

The sound of the leather hitting Jacob’s skin echoed across the clearing. But Jacob didn’t react. His body didn’t flinch. He didn’t even breathe faster.

Gibbard struck him again. And again. But still, Jacob stood unmoving, like a statue.

Eli Strauss stepped forward, grabbing Jacob’s arm and trying to pull him into compliance. But his hand slipped off Jacob’s arm as if it were made of stone. Jacob’s body didn’t bend. His arm didn’t move.

“Get him down!” Gibbard shouted, his voice shaking. “We need more help. Now!”

Within minutes, the other overseers arrived, their faces twisted with confusion and frustration. They grabbed Jacob, attempting to force him to the ground, but he didn’t resist. He just wouldn’t fall.

William Pritchard, a large man from Georgia, joined the effort. He, too, tried to force Jacob down, but it was like trying to move a tree.

No matter how hard they pulled, no matter how many of them were involved, Jacob stayed upright.

Gibbard, his authority now questioned in front of everyone, fired his pistol into the air. The shot echoed through the fog, and within minutes, six more overseers arrived.

Twelve men, all trained, all armed, surrounding one man. And still, Jacob didn’t move.

“You need more men?” Jacob’s voice rang out, low but steady, cutting through the tension. “I ain’t here no more.”

The overseers hesitated. The entire plantation had stopped working. The enslaved people, who had been watching from the fields, stood frozen, staring in disbelief.

Jacob wasn’t fighting them. He wasn’t even struggling. He was simply refusing to be moved.

Colonel Harrington, alerted to the commotion, arrived at the scene, his face dark with fury.

He surveyed the scene—twelve of his overseers, the strongest men on the plantation, all failing to restrain one man. Jacob Terrell, standing in the middle of the clearing, his body unyielding, his eyes locked on Harrington.

“Get him down,” the colonel barked, his voice sharp and filled with authority.

But Jacob didn’t respond. He simply turned away from the colonel and began to walk toward the woods.

For a moment, no one moved. The overseers looked at each other, unsure of how to proceed. The colonel stood, frozen, his hand resting on his pistol. Jacob was walking away, unhurried, his steps slow but deliberate.

“Stop him!” the colonel yelled, but it was too late. Jacob had already disappeared into the trees, his figure swallowed by the fog.

The overseers scrambled after him, but the dogs lost his scent within a mile. The search continued for days, but Jacob was never found. He had simply vanished.

In the days that followed, the atmosphere at Harrington Plantation shifted. The enslaved people, who had witnessed Jacob’s defiance, began to walk differently.

They began to stand taller, to hold their heads a little higher. They didn’t speak of it openly, but they knew what they had seen. They had seen a man defy twelve armed overseers and walk away.

And for the first time, they believed that the system that controlled them wasn’t invincible.

“Sometimes, you just have to stop going along with it,” old Samuel whispered to Martha Clemens, who later recounted the story to her granddaughter.

“Jacob didn’t fight them. He just stopped. And when he stopped, everything changed.”

The incident at Harrington Plantation would be remembered for years, passed down in whispers among those who had witnessed it.

Jacob Terrell had shown them that resistance didn’t always come in the form of violence or flight. Sometimes, it was as simple as standing still and refusing to be moved.

What happened next is still a mystery. Some say Jacob made it to freedom, disappearing into the woods, never to be seen again. Others believe he died trying. But one thing was certain: he had changed everything.

The legend of Jacob Terrell, the man who couldn’t be moved, lived on.

News

The Mother and Daughter Who Shared The Same Slave Lover… Until One of Them Disappeared

The Rosewood Curse: A Love Written in Fire In the sweltering heat of August 1842, the Rosewood plantation lay bathed…

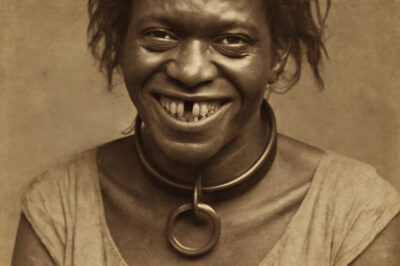

The Master Bought a Toothless Slave To Amuse His Guests…Then She Called Him by His Childhood Name

The Debt of the River: A Legacy of Ashes In the spring of 1853, on the outskirts of Natchez, Mississippi,…

Tennessee 2003 Cold Case Solved — arrest shocks community

The sun was beginning to dip beneath the horizon on the last weekend of July 2003, casting an amber glow…

13-Year-Old Sold to 51-Year-Old Plantation Owner… 8 Years Later, She Was His Worst Nightmare

The Hartwell Massacre: The Story of Rebecca’s Revenge and the Price of Justice The iron gate of the kennel yard…

A young Black girl was dragged into the kennel to be humiliated, left before 10 hunting dogs — but…

The Silent Bond: Naomi and Brutus’ Fight for Survival The iron gate of the kennel yard swung open with a…

Silas the Silent: The Slave Who Castrated 8 Masters Who Used Him

The Silent Revenge: The Story of Silas the Silent In the heart of South Carolina’s low country, the year 1836…

End of content

No more pages to load