On July 12th, 2023, at 9 in the morning, five students from the University of Montana found something they were not supposed to find.

Inside a dead Douglas fur tree 8,200 ft up in the Bitterroot Mountains, 34 m from the nearest highway, they found a body, mummified, curled up in a fetal position as if sealed inside the tree forever.

She was Marlene Cade, 34 years old, a research botonist who had disappeared four years earlier.

They searched for her for three weeks using helicopters, dogs, and hundreds of volunteers.

They searched 300 yard from where she actually was inside a tree.

The forensic examination showed no injuries, no fractures, no signs of a struggle.

But there was still one question that turned all the versions upside down.

How did she get there? The trunk had no holes large enough for an adult, no external damage, no signs of violence, and one more detail that will force investigators to return to the case again and again.

Her diary was found near the body.

The last entry is dated March 16th, 2019, the day she disappeared.

There will be only one line.

The old guard has been found.

He is alive.

He is breathing.

I am going inside.

The summer of 2023 in Montana was a scorcher.

The temperature stayed above 95° F for 3 weeks straight.

Creeks dried up, lakes became 4 ft shallow, and old trees began to die on mass from the drought.

That’s why a group of environmental students found themselves in a remote lost creek meadow that morning documenting the effects of extreme heat on coniferous forests.

Ethan Hullbrook, a third-year student, was in the lead.

He was recording the coordinates of each dead tree.

And when he saw a huge Douglas fur about 12 ft in diameter with blackened bark and bare branches, he stopped to make a note.

It was then that he noticed the gap, a vertical crack at the base of the trunk about 8 in wide.

He took out a flashlight, shown it inside, and froze.

At first, he didn’t understand what he was seeing.

A shape that didn’t fit the definition of wood.

Something blue.

A cloth.

And then a face.

A dried up face with empty sockets and an open mouth.

As if frozen in a mute scream.

Ethan jerked away so hard that he fell.

“Ethan.” Kaye Gentry, a girl from his group, turned around.

She saw him on the ground and ran over.

What happened? He couldn’t say a word, just pointed at the tree with a shaking hand.

Kaye picked up the flashlight and shown it inside.

“Oh my god, there’s there’s someone in there.” Jason Rivers, the oldest of the group, took the flashlight away and looked in himself.

His face turned stone.

“Get away from the tree right now,” he ordered, pulling out his phone.

“No one else comes near.

2 hours and 43 minutes later, a Ravali County Sheriff’s helicopter landed in the clearing.

Sheriff Daniel Gross, a man of about 55 with a gray mustache and weathered face, approached the tree with a medical examiner and a search and rescue specialist.

Brandon Thornton, the specialist, had personally led the search for Marlene Cade 4 years ago.

As he peered through the crack, his fingers holding the flashlight shook.

“A blue jacket, brown hiking boots,” he said quietly.

We found the backpack by the creek, but she was wearing the jacket when she left.

“Is that her?” asked Gross.

“I’d need an official ID.” But yeah, that’s Marlene Cade.

Dr.

Elaine Sanders, the medical examiner, shown her flashlight longer than the others, studying what she could see through the narrow slit.

The dry climate and confined space slowed down the decomposition.

The pose is fetal.

The clothes are partially preserved.

We need to saw through the trunk to get the body out and conduct a full examination.

How did she get there? One of the deputies asked.

Dr.

Sanders walked around the tree, examining the trunk from all sides.

Then she turned to the sheriff.

Sheriff, there are no openings large enough for a person to get in.

This gap is the only opening, and it’s too narrow, even for a child.

Gross frowned.

So, I don’t know, she answered honestly.

I’ve never seen anything like it.

Thornton walked around the tree from the opposite side, checking every inch of the bark.

He came back and shook his head.

No signs of sawing, splitting, or tool damage.

“Maybe she was inside when the tree was younger,” the deputy suggested.

“The tree is about 300 years old,” Dr.

Sanders replied dryly.

That version doesn’t work.

There was a heavy silence.

Only the wind rustled the dry branches of the dead trees around them.

Bring the chainsaw, Gross ordered.

Saw the trunk carefully.

I need to see what’s inside and call the technical team.

Photos, video, document everything.

By the evening, 12 people were working on the lawn.

They sawed the tree slowly, centimeter by centimeter, so as not to damage what was inside.

When the trunk finally fell, splitting in two, everyone present stared in silence at the open interior.

The cavity was natural, the result of an old fire that had scorched the core about 50 years ago.

But what was inside looked unnatural.

Marlene Cad’s body lay at the bottom of the cavity, curled up in a ball facing the wall.

Her skin had dried to a parchment-like state, and her hair was partially intact.

The blue jacket, jeans, and boots were still there.

Dr.

Sanders cautiously approached, crouched down.

She examined the body without touching it.

Then she saw something near the woman’s right hand.

“Sheriff,” she called softly.

“There’s something here.

” Gross walked over, bent down.

Dr.

Sanders carefully pulled out the notebook, wearing gloves.

The cover was faded, but intact.

She opened it to the last filled page.

The handwriting was shaky but legible.

The date March 16th, 2019.

One line.

She read aloud.

The old guardian has been found.

He is alive.

He is breathing.

I am going inside.

There was a dead silence.

Even the wind stopped.

What does this mean? asked the deputy.

No one answered.

Dr.

Sanders turned the page back to the previous entry dated March 15th, the day Marleene left for the mountains.

The usual field notes about the route, weather, vegetation, observations.

Nothing out of the ordinary.

And then this line, the last line.

Take the body to the morg, Gross said, straightening up.

I want to know the cause of death, time of death, everything.

And find me someone who knows about trees.

I want answers as to how she got there.

Thornton looked at the saun tree at the cavity inside at the body at the bottom.

An expression appeared on his face that Gross could not decipher.

Brandon, the sheriff called, “Are you okay?” Thornton was silent for a few seconds, then quietly.

“We’ve been looking for her here.

Right here.

We passed this tree dozens of times.

The dogs were 50 yards from this spot.

The helicopter flew right over it.

How could we not find it? Gross did not know what to say.

That night, as Marlene Cage’s body was transported to the morg in Hamilton, and the sauna tree was left lying on the lawn under guard, Daniel Gross sat in his office and read through old case files, search operation reports, family testimonies, maps of the area.

He had seen all of this four years ago when the case was hot.

Now it was hot again.

But with each page he reread, there were more questions than answers.

On the table in a transparent bag labeled material evidence was Marlene’s diary.

It was open on the last page.

Gross looked at that single line and could not take his eyes off it.

The old guardian has been found.

He is alive.

He is breathing.

I am going in.

What did she mean? What kind of tree was she talking about? And most importantly, how did she get inside it when all the laws of physics and logic said it was impossible? Outside the window, the pines were making noise.

And somewhere in the mountains on the lawn of Lost Creek, there was a sauna tree that had been keeping a secret for 4 years.

And perhaps it still hasn’t given it up completely.

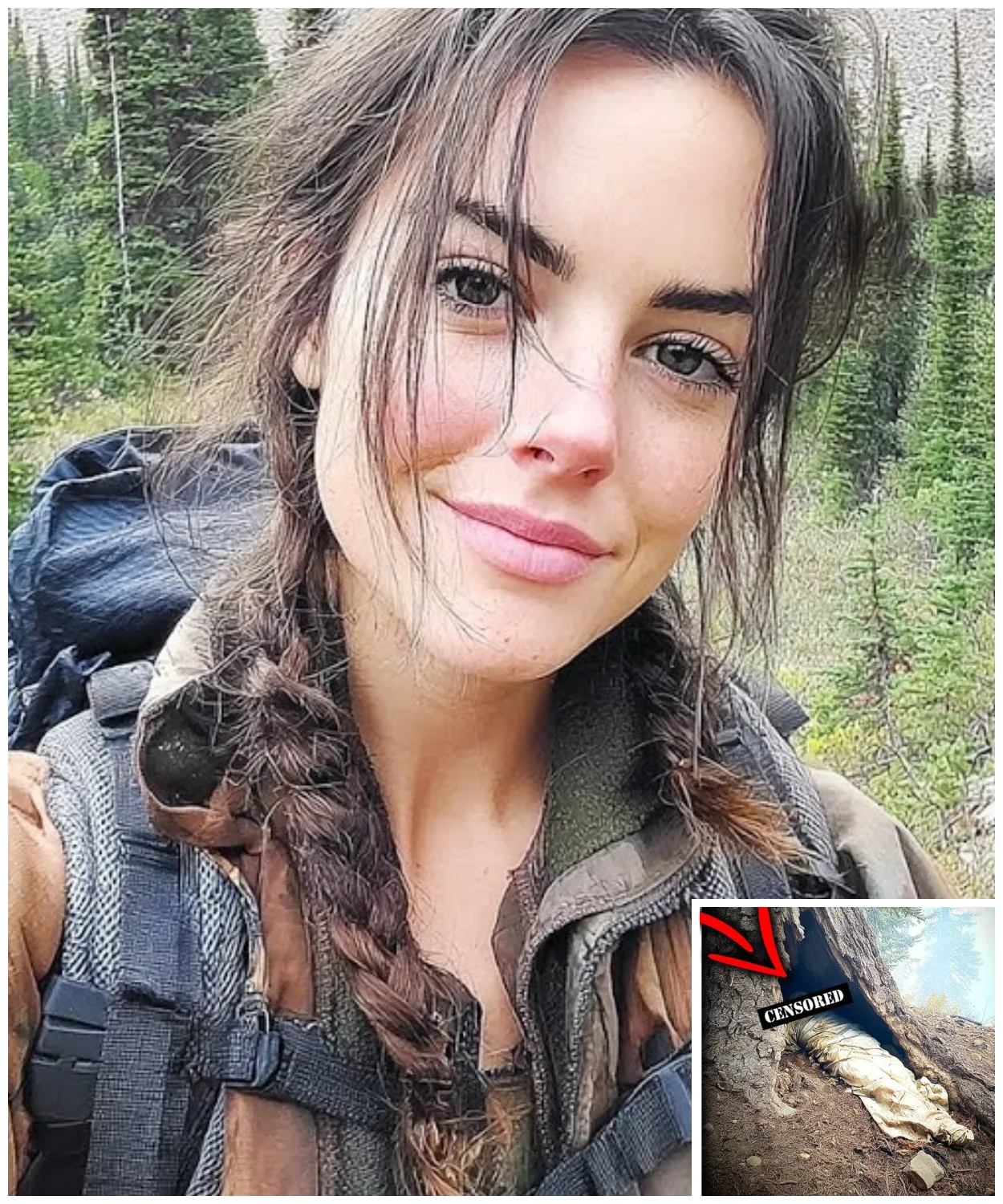

Marlene Cade was born on March 8th, 1985 in Missoula, Montana.

The only child of a ranger and a biology teacher.

Childhood among the mountains, first steps on forest trails, first her burium at the age of seven.

Her father, Robert Cade, took her with him on patrols in the Lolo National Forest, teaching her to recognize trees, read animal tracks, and understand the language of the forest.

Her mother, Elsa, showed her the structure of plant cells under a microscope and explained how trees breathe.

By the time she was 18, Marlene knew that her life would be connected to the forest.

She entered the University of Montana to study botany, specializing in dendrology, the science of trees.

Her master’s thesis was on the ancient coniferous forests of bitterroot.

247 pages of dry academic text.

But behind every sentence, there is a real obsession with the subject.

After university, he worked for the Montana Forest Service, field research, inventory, ecosystem monitoring, a small salary, but the opportunity to spend months in the mountains among the trees that remembered the world before man came.

I met WDE Cade in 2012 at a conference in Helena.

He is a civil engineer.

She is a botonist.

He is talkative and sociable.

She is silent and reserved.

They got married a year later in June of 2013.

A small wedding in Hamilton, 30 guests, most of them conservationists and environmentalists.

They settled in a house on the outskirts of the city overlooking the mountains.

No children.

Marlene said her job required too much time to travel.

Wade did not insist.

Their life was quiet.

Weekdays in the fields and on construction sites, weekends hiking together.

Although in recent years, Marlene traveled more and more alone, WDE stayed at home, tending to the farm and completing projects.

She was not an adventurer.

On the contrary, she was always careful, methodical with detailed routes and communication schedules.

In 19 years of hiking in the mountains, she never had a serious incident.

Wade trusted her experience, but there were things Marlene didn’t tell anyone, not even him.

On March 4th, 2019, 4 days before her 34th birthday, Marleene found an envelope in her mailbox, a plain white envelope with no return address.

The postmark was Missoula, March 1st.

Inside was a single sheet of paper.

The text printed in an old-fashioned typewriter font as if on a mechanical typewriter.

Marlon Cade.

If you really want to find the old guardian, the tree that remembers everything.

The coordinates are below.

Go alone.

The tree does not like prying eyes.

It is waiting.

Then there is a string of numbers.

40 par 62 33 N 114 dig 1847 W Marlene stood on the porch holding the letter and felt her heart speed up.

The coordinates pointed to the Bitterroot Mountains about 38 mi southwest of Hamilton, the Lost Creek area.

The area is inaccessible with no marked trails and bear territory.

But the most important thing is the old guard.

She heard this name in her second year of university.

It is a legend among dendrologists and historians.

A patriarch tree in the Bitterroot Mountains.

A Douglas fur over 400 years old.

Perhaps the oldest tree in the region.

It was called differently.

The old guardian, the witness tree, the greatgrandfather.

But no one knew exactly where it was.

Dozens of expeditions, hundreds of hours of searching, nothing.

Some considered it a myth and now someone sent her the coordinates.

In the evening, she showed the letter to Wade.

They were sitting in the kitchen, unfinished bowls of soup on the table.

Wade read it, frowned.

Who sent this? I don’t know.

The old guardian.

What’s that? A legend.

A tree that has been talked about for decades, but no one has seen it.

if it really exists.

And if these coordinates are true.

Marlene, it looks strange.

An anonymous letter, cryptic wording, remote coordinates.

It could be anyone.

Or someone who really knows something important.

Or someone who wants to lure you into the mountains.

She looked at him across the table.

She knew he was right.

The letter was suspicious.

But there were moments in her profession when her intuition weighed more than logic.

“I’ll check the coordinates on the map,” she said, “and assess the risks.

If it looks dangerous, I won’t go.” Wade sighed.

“Promise me you’ll be careful.” “I promise.” He didn’t look convinced, but he nodded.

He knew that once Marlene made up her mind, there was no stopping her.

March 8th, my birthday, 34 years old.

A quiet evening together, a home-cooked dinner, a bottle of wine.

Wade presented her with new field binoculars, an expensive model with German optics that she had mentioned last summer.

Marlene smiled, kissed him, and said, “Thank you.” But her thoughts were in the mountains near the coordinates from the anonymous letter.

The next week, she prepared.

She studied topographic maps of Lost Creek.

She checked her equipment, a tent, a sleeping bag, 4 days worth of food, and a first aid kit.

She updated her GPS and satellite phone.

I called the Forest Service to check on road conditions and the weather forecast.

March in Montana is unpredictable.

Snow can fall at any time.

Temperatures range from 45° F during the day to 20 at night.

On March 14th, in the evening, she was packing the last of her belongings.

Wade came home from work to find her in the dining room at the table, laying out the contents of her backpack, GPS, compass, maps, diary, food, water, pills, knife, flashlight, batteries, flares, bear spray, emergency beacon.

Marlene, don’t go, he said quietly.

She looked up, surprised by the tone of his voice.

Why? There’s something wrong with all of this.

I can’t explain it, but I have a bad feeling.

Please, Wade, we’ve talked about this.

Then we’ll go together.

I’ll take the weekend.

Marlene shook her head.

The letter says alone.

If the place is really secret, there might be a reason.

I can’t risk spooking whoever knows about the tree.

And that doesn’t make you suspicious.

It does.

But that’s my job, Wade.

To investigate, to search.

If there’s a chance of finding something unique, I can’t let it go.

He didn’t say anything.

Then he came over and hugged her tightly.

Porer, promise me.

Promise me that you will get in touch every 2 hours.

Promise me that you will activate the lighthouse at the slightest danger.

They stood there for so long.

It was getting dark outside.

The mountains blackened against the dark blue sky.

On March 15th, Marlene woke up at in the morning.

The sky was still dark with stars above the mountains.

She got dressed quietly, thermal underwear, warm pants, fleece, and a blue jacket.

She wore her 5-year-old hiking boots, which she trusted to work on any terrain.

When she left the kitchen with her backpack, Wade was standing in the bedroom doorway.

Call me when you get there, he said.

He came over and kissed me long hard.

Come back to me.

I will.

She went out to the SUV, an old green Ford Ranger.

She threw her backpack in the back seat and started the engine.

One last glance at the house.

Wade was in the window waving.

She waved back, turned on her headlights, and drove off.

The drive took 2 and 1/2 hours.

First on asphalt through Sleepy Derby, then on mountain dirt roads that narrowed with every mile.

The last 5 miles were a turtle’s pace, a narrow path, gravel, and stones.

At 9 in the morning, the GPS showed 2 miles to the coordinates.

You can’t go any further by car.

Marlene parked the SUV under a pine tree, got out, and put on her backpack.

The air is cold, crisp, and smells like snow.

The sky is gray.

The forecast promised snowfall in the late afternoon.

The temperature is about 38° F.

Breathing white steam.

I took out my satellite phone and dialed Wade.

I’m parked and on foot.

Coordinates 46 1215 North, 1141 1832 West.

Got it.

Call me at .

I will.

She put the phone down, checked the GPS, and started driving.

The direction was southwest up the hill.

The forest is dense, old Douglas fur, yellow pine, larch, trunks 3, 4, 5 ft in diameter.

The ground is covered with pine needles and fallen leaves.

Silence, only the creaking of branches and the distant cry of a crow.

I walked slowly, checking the GPS every 15 minutes.

The terrain is difficult.

Rocks, hills, juniper thickets.

After an hour, I stopped at a stream, drank, and checked the map.

Another mile to go.

At , I noticed a change.

The trees are less frequent, but larger.

The trunks are 6 or 7 ft tall, over 200 years old.

She stopped and touched the bark.

warm, rough, alive.

At , when the GPS showed 200 yards to the coordinates, Marlene came to a small clearing and she saw him.

The tree stood a little off to the side on a rise, surrounded by young pines, but it was impossible not to notice it.

The trunk was colossal, about 10, maybe 12 feet in diameter at the base.

The bark was dark gray, almost black, covered with lychans and moss.

The branches began at a height of about 20 ft, spreading out in a wide canopy.

The tree was 150 ft tall at eye level.

Marlene slowly approached, unable to take her eyes off it.

Her heart was beating so loud she could hear it.

This was it, the old guardian.

She knew it instinctively without any confirmation.

She walked around it.

The trunk was almost perfectly round with no curvature, no traces of fires, no hollows, only bark that had lived for centuries and roots that went deep into the ground.

She knelt down at the base, took out her diary, and began to make notes.

Approximate measurements, a description of the bark, the nature of the vegetation around.

She took a few photos, but most of all, she wanted to touch it, to feel this power, this time recorded in each ring inside the trunk.

She put both palms on the bark and closed her eyes.

And I felt something strange, a faint vibration, a pulsation, as if the tree was breathing.

I opened my eyes sharply and pulled my hands away.

My heart beat faster.

She looked at her palms, then at the tree.

imagination,” she said to herself.

But she knew it was something else.

At , the satellite phone rang.

“Wade, I’m fine.

I found what I was looking for.

The tree?” “Yes, it’s incredible, Wade.

It’s so big, so old.

I’ve never seen anything like it.” “Okay, go back inside.

I want to take some more measurements.

I’ll be back in the SUV by 4.” Marlene, it’s almost noon.

It’ll be dark around 6K.

I’ll make it.

I promise.

I’ll call you at one guy.

Okay, I’m waiting.

She put the phone down and turned to the tree.

She walked around the other side and froze.

There was a gap at the base of the trunk about 5 ft high.

A vertical crack in the bark about a foot wide and 2 ft high.

It was dark, like an entrance.

Marlene moved closer, took out her flashlight, and shown it inside a cavity, a natural chamber inside the trunk.

She couldn’t estimate how deep it was, but it seemed to be quite large.

She straightened up and took a step back.

I looked at the gap, then at the sky.

The clouds were thickening, the wind was getting stronger, and then she felt it again.

A vibration, a pulsation, as if the tree was breathing.

She took out her diary and quickly wrote down, “March 16th, .

The old guardian has been found.

He is alive.

He is breathing.

I’m going inside.” She put the diary in her pocket and went to the crack.

I looked inside again.

It was dark, but something was pulling her in.

Something that could not be explained.

She stretched out her hand, touched the edge of the crack, and then she took a step forward.

The forest behind her became quiet.

Even the wind stopped rustling the branches.

It was as if the world had frozen, waiting for what would happen next.

At on March 15th, Marlene was supposed to call.

She didn’t.

WDE Cade was sitting in his office at a construction site on the outskirts of Hamilton, staring at his phone.

1301 1305 1309 not a single call.

Maybe there’s no signal, he said to himself.

The Bitterroot Mountains are a dead zone for conventional cell phone service.

That’s why Marlin took a satellite phone.

But even satellite communication sometimes fails in deep gorges among high cliffs.

At , he called himself.

Marlene’s satellite number.

The signal came through, but no one answered.

After the eighth ring, he got an answering machine.

Marlin, it’s me.

Call me when you get this.

I’m worried.

I returned to the construction project drawings and tried to concentrate.

It was not working.

My eyes kept slipping to the phone on my desk.

At , he called again.

The same result.

Marlene, please call me back.

I’m really worried.

At 4 in the evening, he put the blueprints down, told the foreman he was going home.

He got into a pickup truck and drove off.

All the way, he kept the phone on the passenger seat to hear if it rang.

The phone was silent.

I arrived home at .

Marlene should have been here by now.

The SUV was supposed to be in the driveway.

The driveway was empty.

He entered the house.

The house was silent.

No sign of her return.

No jacket on the rack, no shoes by the door, no backpack in the dining room.

Wade sat down in the kitchen and dialed her number again.

The machine answered.

At in the evening, the sun began to sink behind the mountains.

The sky above Bitterroot was colored red and orange.

The temperature outside the window was dropping.

The forecast promised nighttime frost of 25° F.

If Marlene was out in the mountains somewhere with no shelter.

No, she’s experienced.

She knows what to do.

Maybe she decided to spend the night in the woods, set up a camp.

Although she didn’t take a tent, she planned to return in a day.

At 7, Wade dialed the Montana Forest Service.

He asked if there had been any reports of incidents in the Lost Creek area.

The receptionist replied that there had been no reports.

She advised me to wait until the morning.

My wife went there this morning.

She was supposed to return at .

She hasn’t been in touch.

Sir, people often lose contact in the mountains.

That’s normal.

If she’s not back by tomorrow, call the sheriff’s office tomorrow at a temperature of 25°.

Sir, I understand your concern, but it’s impossible and dangerous to organize a search operation at night.

Wait until morning.

Wade hung up the phone.

He looked at the phone, then at the clock on the wall.

.

At 8 in the evening, he sat in the darkness of the living room without turning on the light.

Night had fallen outside the window.

Black, starless clouds covered the sky.

The thermometer outside the window showed 28° and continued to fall.

Marlin is out there somewhere.

In the mountains, in the dark, in the cold.

At 9, Wade dialed the Ravali County Sheriff’s Office.

Sheriff Daniel Gross picked up after the third ring.

He sounded sleepy and irritated.

His shift ended at p.m.

Sheriff Gross here.

Sheriff, my name is Wade Cade.

My wife is missing in the Bitterroot Mountains.

She hasn’t been in touch since day one.

Please, I need your help.

Gross asked a few questions.

name of the missing person, age, description, last scene, coordinates, what equipment she had with her.

Wade answered, trying to keep his voice steady, but his hands were shaking.

She’s an experienced traveler, Gross said.

She has a satellite phone, GPS, and emergency beacon.

Did she activate the beacon? No.

I checked the online system.

The beacon is not activated.

That’s good.

It means she’s not in critical danger.

Maybe she just decided to spend the night in the woods.

She didn’t take a tent.

She planned to return in a day.

Gross side.

Mr.

Cade, I understand your concern, but it is technically impossible to organize a search operation at night.

We can’t see in the dark.

We can’t fly helicopters.

And dogs don’t work as efficiently.

I will personally organize a group at dawn.

I promise.

Dawn is at in the morning.

That’s nine more hours.

Mr.

Cade, at 25°, a person without shelter may not survive the night.

Your wife has experience.

She knows how to keep warm.

If she is somewhere under a tree in a sleeping bag with food and water, she will survive the night.

But if we send people there now, they may get lost or injured, and then we’ll have more missing people.

Wade was silent.

He knew the sheriff was right, but every cell in his body screamed, “Go now.

Look now.

Find her now.” “Dawn,” Gross repeated, “I promise we’ll do our best, and you try to get some sleep.

You need your strength.” He hung up the phone.

WDE sat in the dark for another hour.

Then he went online and looked for maps of the Lost Creek area.

He printed them out, marked the coordinates Marlene had given him in the morning.

46 1215 north 114 1832 west.

I imagined her walking through that area.

Dense forest, rocky slopes, streams.

Where was she going? What was she looking for? That tree from the anonymous letter.

He walked over to her desk in the office and began to sort through the papers.

He was looking for that letter.

He found it in a folder with field notes, a white envelope, a sheet of paper with coordinates.

The old guardian, a tree that remembers everything.

Go alone.

Wade clutched the sheet in his hand.

Who sent this? Who knew about the legendary tree? And why had Marlene believed in anonymous letters so easily? The clock on the wall struck midnight.

The temperature outside the window dropped to 23°.

Wade had been up all night.

March 16th.

Dawn came at .

Gray, overcast sky, temperature 21° F.

At 7 in the morning, Sheriff Gross assembled the first search team outside the sheriff’s office in Hamilton.

Three deputies, four Forest Service rangers, and two volunteers from a local search and rescue organization.

Two German shepherds trained to find people.

Wade arrived at .

At first, Gross subjected to his participation.

Relatives of the missing often interfere with operations, act emotionally, and create additional problems.

But Wade insisted, “I know the mountains.

I know how it thinks.

I know her habits.

I can help.

” Gross looked at him, his face gray from a sleepless night, his eyes red, his hands clenched into fists, and nodded.

“Very well, but you listen to me and Thornton.

No amateurishness.” Brandon Thornton, a man in his 40s with a military bearing and a face weathered by years of working in the mountains, led the county search and rescue team.

32 years of experience, hundreds of operations, dozens of lives saved.

He walked up to Wade, put his hand on his shoulder.

“We’ll find her,” he said quietly.

Wde nodded, not trusting his voice.

At , the convoy of four SUVs left for the mountains.

“March, in the morning.

The search team reached the coordinates of Marlene’s last call.

The SUV was parked under a pine tree, exactly where she had left it.

The doors were locked and the windows were intact.

WDE walked over and looked inside.

Nothing in the back seat.

Everything was clean.

Marlene was always neat.

The dogs picked up the scent right away.

They sniffed the driver’s seat, barked, and pulled the dog handlers to the southwest.

The group moved after them, 10 people in a chain, two by two, keeping sight of each other.

The forest here was dense, old.

Douglas fur trees rose 150 ft up, their trunks thicker than the girth of two people.

The ground was covered with a thick layer of pine needles that muffled footsteps.

The temperature was about 30° with no sun breaking through the clouds.

“Marlin!” WDE shouted every 50 yards.

Marlin, can you hear me? Silence in response.

Only the wind in the branches and the creaking of the old trees.

After half a mile, one of the dogs stopped by a stream.

The handler bent down and picked something up off the ground.

“A print!” he shouted.

The group gathered around.

In the soft soil near the water, there was a clear bootprint, a woman’s, size seven.

The tread matched the brand Marleene wore.

Thornton crouched down and examined the print with his fingers.

It was fresh, yesterday’s.

She walked steadily without haste.

She didn’t run, didn’t stumble.

She knew where she was going.

One of the rangers said.

Wade looked at the trail, feeling a strange mixture of relief and anxiety.

She was here, alive, moving.

But where was she going? The group moved on.

The dogs led them stubbornly, not losing the trail.

Half a mile later, another sign.

A broken juniper branch 4 feet high.

“She came through here,” Thornton confirmed.

A tall woman.

The branch caught on her backpack or shoulder.

But a 100 yards further on, the dog suddenly stopped at a large rock.

They barked, sat down, and looked at something at the base.

Wade ran up first.

I saw it and my heart sank.

A backpack, a blue marlin hiking backpack, neatly placed next to the rock, zipper zipped up.

Thornton carefully picked up the backpack, unzipped it, and looked inside.

The food supplies were in place.

Water, two bottles, first aid kit, flares, bear spray, spare batteries.

He paused, checking further.

No GPS, no satellite phone, no field diary.

Why would she leave her backpack? One of the sheriff’s deputies asked.

Wade stood silently looking at the backpack.

It didn’t make sense.

Marlene would never ever leave a backpack behind.

A backpack is survival in the mountains.

Maybe it got too heavy, the ranger suggested, and she decided to lighten the load on the steep climb.

Thornton shook his head.

The backpack weighs 20 lb, 25 at most.

For an experienced hiker, that’s nothing.

And look at the way it’s standing.

Neatly, not abandoned.

Why? Wade asked horarsely.

No one answered.

The dogs picked up the trail again and led the group on, but after a hundred yards, they stopped at a small stream.

They started circling, sniffing the ground, whining.

The trail broke off.

The dog handler said, “If she crossed the stream, we need to look for a way out on the other side.” The group split up.

Five went up the creek.

Five went down.

Wade went upstream with Thornton’s group.

They searched for 2 hours.

They checked every meter of the shore, looking for traces of exit from the water.

There was nothing.

The stream ran between the rocks, cold, clear, ruthlessly washing away any traces.

At in the afternoon, a sheriff’s helicopter appeared over the forest.

It circled low, the operator with a thermal imager scanning the area through the treetops.

Wade looked up, listening to the roar of the blades, and prayed.

Find her.

Please find her.

An hour later, the helicopter took off.

Thornton received a message on the radio.

The thermal imager hadn’t detected anything.

The temperature during the day was about 32°, too warm to clearly distinguish a human body among the sunheated rocks and trees.

By evening, the search area had expanded to two square miles.

54 people combed the forest.

Six dogs checked every ravine and crevice.

Two helicopters flew over the mountains when the clouds allowed.

They shouted Marlene’s name in every direction.

There was no response.

As the sun began to set, Gross ordered them to return to base camp.

It was dangerous to search in the dark.

People could get hurt, get lost themselves.

WDE didn’t want to go.

She’s out there somewhere.

She might be injured, unable to move.

If we leave her here another night, “Mr.

Cade,” Gross said firmly, “you’re not helping anyone if you break your leg in the dark.

We’ll continue tomorrow at dawn.

Volunteers will join us.

will expand the area.

That night, Wade spent the night in a tent on the lawn near Marlin’s SUV.

He didn’t sleep.

He lay in his sleeping bag, listening to the sounds of the forest, the rustling of the wind, the creaking of the trees, the distant hoot of an owl.

I thought about her.

Where is she now? Is she alive or not? Why did she leave her backpack behind? What was she looking for in these mountains? Outside the tent, the temperature dropped to 20°.

July of 2023, 4 years after the disappearance of Marlene Cade.

The case has long been closed.

The files are in the Ravali County Sheriff’s Office in a box labeled Cade Marlene.

Disappeared on 0315209.

Status unsolved.

Official probable death as a result of an accident in the mountains.

The body has not been found.

The search lasted 3 weeks.

160 volunteers, 12 dogs, four helicopters.

They searched eight square miles around the last known location.

We checked every cave, every ravine, every cluster of boulders.

They found a backpack, bootprints, a piece of blue cloth on a juniper branch.

Marlene Cade was not found.

On April 5th, 2019, Sheriff Gross announced that the active phase of the search was over.

The case is now an open investigation.

Any new information will be verified, but large-scale operations are suspended.

Marlene’s parents, Robert and Elsa Cade, held a memorial service without a body in June 2019.

A small church in Missoula, 30 people, most of them colleagues from the forest service.

an empty coffin, a photo of Marlene on the table, smiling in a field jacket with a backdrop of mountains.

WDE sat in the front row looking at the photo, not crying.

He couldn’t.

He felt an emptiness that nothing could fill.

A year later, he sold the house in Hamilton.

There were too many memories.

Her desk in the study, her shoes by the door, her cup in the kitchen.

He moved to Missoula, found a job with another construction company.

I tried to start over.

It didn’t work out.

Every mountain, every forest reminded me of her.

The Lost Creek area became a local legend.

Local hunters and tourists avoided the area.

There were rumors of a cursed place where people disappeared.

In reality, however, not a single incident had been recorded there in 4 years.

Forest Service rangers sometimes patrolled the area, checked the trails, and recorded the condition of the trees.

None of them liked to go there.

Something about that forest made them uncomfortable.

Too quiet, too dense, too many old trees standing like guardians of some secret.

Wade came there twice a year.

On March 8th, her birthday, and in September, when they got married, he parked his SUV in the same spot where her Ford Ranger had been parked four years earlier.

He walked the same path to the place where the backpack was found.

I sat by the stone for hours.

I did not pray.

I did not believe in God after what happened.

I just sat there looking at the mountains trying to understand.

What was she looking for? That tree? the old guard from the anonymous letter.

Why did she go there alone? Why didn’t she listen to him when he asked her not to go? There were no answers, only the mountains, indifferent and ruthless.

The summer of 2023 was hellish.

Temperature records were broken every week.

In June, Montana recorded 105° F, the highest temperature ever recorded.

The drought was killing forests.

Creeks dried up.

Lakes became 5 ft shallow.

Trees, even those that had survived centuries, began to die on mass from lack of moisture.

Forest fires broke out every day.

By mid July, the fire had destroyed more than 40,000 acres in southern Montana.

Smoke clouds blocked the sun and the air rire of harum.

Chapter 6.

a casual find.

It was July 12th, 2023, in the morning.

Five University of Montana students stood in a clearing in the Lost Creek area, 34 mi from the nearest highway.

The temperature had already risen to 82° F.

Although the day had just begun, the air is dry and smells like smoke from distant wildfires.

Ethan Hullbrook, Kaylee Gentry, Jason Rivers, Marissa Chen, and Colin Drake.

All students in the Department of Environmental Studies, ages 19 to 22.

On the fifth day of fieldwork, the task is to document the effects of extreme drought on ancient coniferous forests.

Up to this point, they have recorded 73 dead trees over an area of 14 square miles.

Douglas furs, yellow pines, and lodgepole pines were all dying from lack of water.

The tree in the clearing was to be the 74th on the list.

Ethan was the first to approach it, taking out his notebook.

A huge Douglas fur about 12 ft in diameter at the base.

The bark was blackened, peeling off in large layers.

The branches are bare without needles.

The height is about 140 ft.

This has got to be the biggest dead tree we’ve ever seen.

Kaye said as she came closer.

Look at the girth.

300 years old at least.

Ethan walked around the tree on the left side looking for a better angle for the photo.

And he saw a gap, a vertical break in the bark about 5 ft off the ground, about 8 in wide.

I got closer.

The gap went deep into the trunk, dark inside.

I took out a flashlight from my backpack.

The same small tactical flashlight I used for night hikes.

I shown it inside.

At first, I did not understand what I was seeing.

Forms, something blue, fabric, then contours that should not have been inside the tree.

An angle that resembled a bent knee.

Something round like a face.

Ethan jerked away so hard he fell on his ass.

The flashlight flew out of his hand and rolled across the gravel.

His heart was pounding somewhere in his throat.

His breath was ragged.

Ethan.

Kaye turned around.

What happened? He gestured to the tree, unable to speak.

Kaye ran over, picked up her flashlight, and walked over to the gap.

She shown it inside.

3 seconds of silence.

Then she stepped back, pressing her hand to her mouth.

Oh my god, she whispered.

There’s There’s someone in there.

Jason Rivers, the oldest of the group, ran over and picked up a flashlight.

He peered through the crack.

Everybody get away from the tree, he ordered quietly but firmly.

Right now.

What is it? Marissa, the smallest of the group, asked.

A body, Jason, answered, pulling out his phone.

A dead body.

The next two hours were spent in tense anticipation.

Jason called the emergency services, gave the coordinates, described the find.

The dispatcher said, “Stay put.

Don’t touch anything.

Help is on the way.” The students sat in the shade 30 yard from the tree, drinking water from thermoses, trying not to look in that direction.

Ethan was shivering even though the temperature had risen to 90°.

How long has it been there? Colin asked quietly.

I don’t know, Jason answered.

It looked dried out, mummified.

Who could it be? No one answered.

At , a helicopter appeared over the clearing.

It landed a/4 mile away, kicking up a cloud of dust.

Four people got out.

Ravali County Sheriff Daniel Gross, two deputies, and a medical examiner.

Gross approached the students, introduced himself, and asked a few questions.

Who found it? When? Who else looked inside? Did they touch anything? Then he went to the tree.

He took a powerful flashlight from the deputy, leaned into the gap, and shown it.

I stood there for a long time, silently.

Then he straightened up, took off his hat, ran his hand through his hair.

“Thorn,” he called.

Look.

Brandon Thornton, the same search and rescue specialist who had led the search for Marlene Cade four years earlier, walked over.

He peered through the crack.

His face remained impassive, but the fingers holding the flashlight trembled.

“Blue jacket,” he said quietly.

“Brown hiking boots.” He was silent.

“Oh god, it’s her.” “Are you sure?” “I’d need an official ID, but yeah, that’s Marlene Cade.

Gross looked at the tree, then at the clearing around it, then back at the tree.

Four years, he said quietly.

Four [__] years she’s been here.

300 yd from where we found the backpack.

Dr.

Ela Sanders, the medical examiner, walked over to the crevice.

She shined her flashlight for a long time, changing angles, studying what she could see.

“The body is mummified,” she said.

The dry climate, the confined space slowed down the decomposition.

The pose is fetal.

Clothes are partially intact.

She walked around the tree, examining the trunk.

Sheriff, there are no openings here large enough for a person to fit through.

So, how did she get in? I don’t know.

We need to cut the trunk to get the body out and conduct a full examination.

By evening, 12 people were working on the lawn.

They carefully sawed the tree centimeter by centimeter.

When the trunk fell, splitting in two, everyone saw the inside.

The cavity was natural, the result of an old fire.

At the bottom, curled up in a ball, was the body of Marlene Cade.

Dr.

Sanders crouched down and examined her without touching her.

She saw something near her right hand, a small leatherbound notebook.

She took it out carefully.

She opened it to the last page.

The handwriting was shaky.

The date, March 16th, 2019.

One line.

She read it aloud.

The old guardian has been found.

He is alive.

He is breathing.

I am going inside.

There was dead silence.

What does this mean? The deputy asked.

No one answered.

Marlene Cade’s body was taken to the Morgan Hamilton on July 13th at 8 in the evening.

Dr.

Elaine Sanders began a full examination the next morning.

WDE Cade was sitting in the waiting room of the sheriff’s office when he got the news.

Gross walked in, sat down across from him, and was silent for a long time before speaking.

We found her, Wade.

Wade stared at him, not understanding.

Where? in the Bitterroot Mountains, Lost Creek area.

The student stumbled upon it by accident.

She’s alive.

Gross shook his head.

I’m so sorry.

Wade didn’t cry.

He sat still, staring at one point.

For 4 years, he had been preparing for this news.

He had known for 4 years that she was dead.

“How?” he finally asked.

“We don’t know for sure yet.

The medical examiner is conducting an examination.

But Wade, there’s something strange.

What? We found her inside a tree.

Inside the trunk.

Wade looked at the sheriff, not understanding.

What do you mean inside? The tree had a natural cavity.

She was inside that cavity.

We don’t know how she got there.

The examination lasted 3 days.

Dr.

Sanders worked methodically documenting every detail.

The conclusions were as follows.

The body was naturally mummified.

The dry climate inside the cavity, the absence of moisture and insects slowed down the decomposition.

The skin dried to a parchment-like state and the internal organs were partially preserved.

No injuries, no fractures, no signs of violence, no wounds, cuts, bruises.

Cause of death, most likely hypothermia or dehydration, possibly both factors at the same time.

It is impossible to determine for sure due to the condition of the body.

Time of death approximately 24 to 48 hours after the disappearance, that is on March 17th or 18th, 2019.

Clothing on the body, blue tourist jacket, black thermal underwear, gray pants, brown shoes.

Everything matches the description provided by the man during the disappearance.

Findings on the body.

A field diary with a leather cover.

A GPS navigator battery discharged.

A satellite phone battery discharged.

But the biggest mystery remained unsolved.

How did she get inside? A dendrological examination of the tree showed the Douglas fur is about 320 years old.

It died of drought in the summer of 2023 as evidenced by the last annual rings.

The internal cavity was formed as a result of a fire about 50 years ago.

The fire scorched the heartwood, but the tree survived, continuing to grow its outer shell.

The size of the cavity at the base is approximately 4 ft wide, 5 ft long, and 12 ft high.

The only opening to the outside, a slit 5 ft high, measuring about 12 in wide and 24 in high.

An expert dendrologist, Professor Marcus Granger of the University of Montana, examined the saun trunk in person.

His conclusion was unequivocal.

The opening is too narrow for an adult to fit through.

Even a child would have difficulty.

A woman 5′ 6 in tall and weighing 130 lb like Marlene Cade according to medical records could not physically squeeze through a hole that size.

“So, how did she get in?” Gross asked.

“I don’t know,” Granger replied honestly.

“It defies logical explanation from a physics standpoint.

On July 23rd, Gross called a press conference.

He announced the official results of the investigation.

Marlene Kade died in the Bitterroot Mountains on March 15th or 18th, 2019.

The cause of death was the influence of natural factors, probably hypothermia.

The circumstances under which he ended up inside the tree remain unclear.

The case is being closed as an accident.

The journalists were bombarded with questions.

How did she get inside? Why didn’t search dogs find her four years ago? What does the entry in her diary mean? Gross answered with restraint, avoiding speculation.

Facts are just facts.

The rest is speculation.

WDE took the body for burial.

This time, the coffin was not empty.

The ceremony was quiet with no press, just family and close friends.

Marlene’s parents, Robert and Elsa, had aged 10 years in those four years.

They sat in the front row holding hands.

WDE stood by the coffin looking at a photo of his wife, the same one that stood at the memorial service four years ago, smiling in a field jacket against the backdrop of mountains.

The old guard has been found.

He is alive.

He is breathing.

I am going inside.

What did she mean? What tree was she talking about? Why did she write it is alive? Why breathing? There were no answers, only questions that multiplied every day.

On August 8th, the Montana Forest Service placed an official plaque in the clearing where the tree had stood.

The saun trunk was still there, too heavy to transport.

The sign was laconic.

Dangerous area.

No entry allowed by order of the Montana Forest Service.

No mention of the Marlins, no explanation of why the area is dangerous.

Local rangers quietly avoided the area.

The students who found the body never returned.

And Wade Cade came there once a month.

He parked his SUV, walked to the clearing, and sat down by the sa trunk.

He would look at the dark cavity inside where his wife had been lying for 4 years and tried to understand.

The tree was silent.

The mountains were silent.

There were no answers.

Only silence.

Absolute.

Irreversible.

News

3 Years After a Tourist Girl Vanished, THIS TERRIBLE SECRET Was Found in a Texas Water Tower…

In July of 2020, a 22-year-old tourist from Chicago, Emily Ross, disappeared without a trace in the small Texas town…

Brothers Vanished on a Hiking Trip – 2 Years Later Their Bodies Found Beneath a GAS STATION FLOOR…

In June of 2010, two brothers, Mark and Alex Okonnell, from Cincinnati, Ohio, went on a short hike in Great…

Backpackers vanished in Grand Canyon—8 years later a park mule kicks up a rattling tin box…

The mule’s name was Chester, and he’d been carrying tourists and supplies down into the Grand Canyon for 9 years…

Woman Vanished in Alaska – 6 Years Later Found in WOODEN CHEST Buried Beneath CABIN FLOOR…

In September of 2012, 30-year-old naturalist photographer Elean Herowell went on a solo hike in Denali National Park. She left…

Two Friends Vanished In The Grand Canyon — 7 Years Later One Returned With A Dark Secret

On June 27th, 2018, in the northern part of the Grand Canyon on a sandy section of the Tanto Trail,…

3 Students Vanished In The Cambodian Jungle — 5 Years Later One Returned

There is nothing more strange than human disappearance, not death, disappearance itself. When the body is not found, the soul…

End of content

No more pages to load