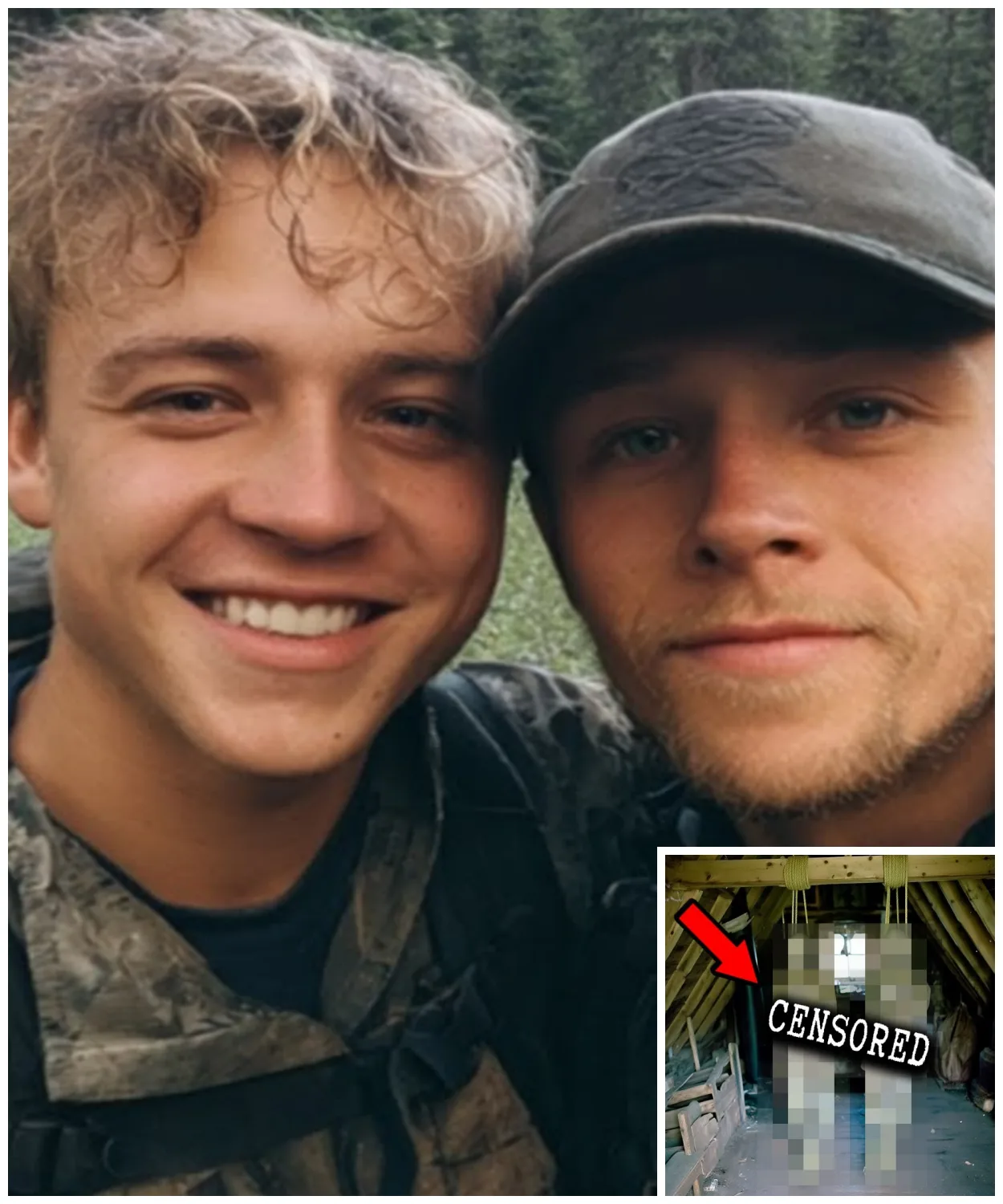

Two Tourists Vanished in Canadian woods — 10 years later found in an OLD CABIN…

In November 1990, the case of Matthew Kelly and Brendan How was officially closed.

The St.Louis County Coroner’s verdict, probable drowning.

Their bodies were never found.

But the evidence left at their campsite on Namokan Narrows Island told a very different story.

A story that had nothing to do with a sudden storm or a cap-sized canoe.

All the facts pointed to the fact that they did not leave the island of their own accord and that their disappearance was not an accident but something else.

It all began on Monday, September 3rd, 1990.

It was Labor Day.

Matt Kelly, 22, and Brendan How, 21, had just graduated from the University of Minnesota.

They were experienced hikers, not noviceses, and this was to be their last big trip before starting adult life.

They planned a week-long canoe trip through Voyagers National Park.

Voyagers National Park is not a place where you can walk along paved paths.

It is a maze.

Thousands of acres of water, rocks, and more than 500 islands scattered along the border with Canada.

In 1990, there was no cell phone service or GPS.

You registered with the rangers, picked up a map, a compass, and a walkie-talkie that only worked over short distances.

If you got into trouble, you were on your own.

That Monday, Matt and Brendan registered at the Ranger Station in Crane Lake at the southern tip of the park.

They left their car in the parking lot, provided their route, and obtained a camping permit.

Their main base was to be Namakan Narrows Island number 64.

It is a narrow strip of land 64 acres in size which essentially controls the narrow straight between Lake Namakan and Lake Kabatogama.

It was a remote, quiet place.

Their plan was simple, a week of fishing and hiking.

They were to return to the station at Crane Lake the following Saturday, September 8th, at p.m.

Saturday, September 8th.

had passed.

At , Matt and Brendan had not shown up.

This did not cause immediate panic.

Tourists are often late.

The wind could have blown them off course, or they might have simply decided to stay another night.

But by 700 p.m., as darkness began to fall, the ranger on duty at Crane Lake Station began to worry.

Their car was still in the parking lot.

At p.m., when it was almost dark, the rangers sent a patrol boat to check their campsite on Namakan Narrows Island.

The rangers arrived at the island at dusk.

The first thing they saw was a canoe.

It was an Oldtown Ponobscot 16, green in color, 16 ft long.

It was just lying on the sandy beach, untethered.

It had not been pulled out and secured as experienced tourists do, but it had not been carried away by the current either.

It was just lying at the water’s edge.

About 20 yard from the shore in a small grove stood their tent.

It was a blue Eureka Timberline, too.

The tent was fully assembled, the entrance zipper closed.

The rangers called out to Matt and Brendan.

There was no response.

They opened the tent.

Inside were two holofll sleeping bags, unrolled but looking unused.

Two backpacks lay nearby.

Inside the backpacks were their personal belongings.

Wallets, driver’s licenses, a change of clothes, and the keys to the car left in the parking lot at Crane Lake.

Everything was there.

Near the camp at a height of 4 1/2 m between two trees hung a Garcia food container.

It is a standard black barrel designed to protect food from bears.

It was untouched.

This immediately ruled out the possibility of a bear attack.

A bear would have gone for the food first.

The fire pit was cold.

When the rangers checked the ashes, they were completely wet, not just cool.

Heavy rain had fallen in the area on Thursday.

This meant that the fire in this pit had not been burning since at least last Wednesday, if not longer.

Matt and Brendan did not disappear on Saturday.

They disappeared sometime in the middle of the week.

No signs of a struggle, no traces of blood, no notes.

The camp was perfect, but empty.

The rangers found only two strange details.

There was an empty folders coffee can on a log by the fire.

And at the water’s edge, near where the canoe had been, there was a single boot.

It was a left hiking boot, size 11.

It was later identified as belonging to Matt Kelly.

And the strangest thing was that the boot was pointing toward the lake.

It was as if its owner had taken one last step and entered the water, but the other boot was nowhere to be found.

On Sunday, September 9th, a full-scale search and rescue operation began.

First, rangers combed the entire island, 64 acres.

Nothing.

On Monday, September 10th, boats from the St.

Louis County Sheriff’s Office joined the search.

They began combing the bottom around the island.

The water in Lake Namakan is dark and very cold.

Visibility is almost zero.

On Tuesday, September 11th, a Bell 206 helicopter was sent up.

It circled the island and surrounding waters for hours, looking for any bright spots, clothing, equipment, nothing.

On Wednesday, September 12th, divers arrived on the scene.

They dived in the area where the boot was found and in the area of the straight.

The bottom was littered with sunken trees.

It was slow and dangerous work and it yielded no results.

That same day on Wednesday, search dogs were brought in from Elely, Minnesota.

These were dogs trained to pick up scents.

They were given items from the sleeping bags to sniff.

The dogs picked up a scent from the tent, but it was weak.

They completely ignored the spot where the boot was found near the water.

Instead, they led the dog handlers across the entire island to its eastern tip.

It was a rocky cape that dropped down to the water, and there, at the roots of a large old birch tree, the trail ended.

The dog stopped, began to circle around in confusion, and lay down.

The dog handlers said that the trail had ended.

It did not go into the water.

It did not lead back into the forest.

It simply disappeared on that cape.

The active search continued for almost 2 weeks.

Neither Matt nor Brendan nor their equipment nor the second shoe were ever found.

In November 1990, when the lake began to freeze, the case was transferred to the archives.

The official cause was probable drowning.

This version did not satisfy anyone who had seen the scene.

If they had drowned after capsizing the canoe, why was the canoe on the shore? If they had drowned, why was their camp set up? And if they had both drowned, who had placed Matt’s shoe with the toe pointing toward the water? For 10 years, Matt and Brendan’s families lived with this version.

For 10 years, they were considered missing, presumed drowned.

Until an autumn day on September 11th, 2000 changed everything.

10 years.

For 10 years, the case of Matthew Kelly and Brendan How sat in the St.

Louis County Archives.

The official verdict of probable drowning satisfied no one, but there was nothing to challenge it with.

For 10 years, their families lived without answers.

Matt’s car remained in the parking lot at Crane Lake until his father finally took it away.

A size 11 shoe found near the water and an Oldtown Ponobscot canoe were the only clues, and they revealed nothing.

For 10 years, the forest and the water kept their secret.

Then on September 11th, 2000, that secret was revealed in the most brutal way.

That day, a crew of loggers from Wire Hooser was working a few miles north of Lake Namakan.

They weren’t tourists.

They were professionals cutting a new trail for timber transport in the dense, impenetrable forest.

Their site was about 5 1/2 miles north of Namakan Narrow’s Island.

To be clear, that’s 5 1/2 miles in a straight line through swamps and impenetrable thicket far from the water.

One of the bulldozer operators clearing debris stumbled upon a structure.

It was an old hunting cabin sunk into the ground.

Judging by its construction, it had been built back in the 1940s.

It had long since fallen into disrepair.

The shingle roof had collapsed inward.

The log walls were covered with mold.

The loggers approached to make sure there were no vagrants or possibly dead animals inside.

What they saw inside prompted them to immediately contact the sheriff’s office.

Inside the half-colapsed hut in the dim light, among the rubbish and fallen beams, were human remains.

These were not just remains.

It was a place of execution.

Two skeletons were tied to the central support beams of the roof.

They were tied not with rope, but with thick 10 mm nylon rope.

Judging by the preserved fragments, they had once been suspended so that they barely touched the floor.

Both had their hands tied behind their backs.

Their legs were also tied together and tied to the lower beams of the wall.

Forensic experts who arrived at the scene noted the knots.

These were complex nautical knots tied with great force.

It was impossible to cut them, so they had to be sawed off.

The clothing on the remains had almost completely decayed, but fragments remained.

These were the remains of Patagonia fleece jackets and Levis’s jeans.

These were models that were popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

This was the first clue.

Later, dental records would confirm that these were Matthew Kelly and Brendan How.

But they weren’t alone.

In the far corner of the cabin, behind an overturned table, lay a third skeleton.

This man was dressed in the remains of a camouflage uniform.

Unlike Matt and Brendan, he was not tied up.

He was lying on his back, and the entire front of his skull had been smashed in.

A carbine lay in the mud next to his right hand.

The weapon was so rusted that there were holes through the barrel, but the model was identifiable.

It was a Remington semi-automatic carbine, model 7400.

The crime scene investigation team arrived.

The scene was horrific.

It didn’t look like a drug deal gone wrong or a random murder.

It was methodical.

The case of the drowned students was immediately pulled from the archives.

Now, the investigators had three bodies and a cabin 5 and a half miles from the students last known location.

But how did they get there? Their canoe, the old town Ponobscot, was never found.

Not on the island, not on the mainland.

There were no signs that they had crossed 5 1/2 miles of rugged forest on foot.

It appeared that they had been brought to this cabin.

But by whom and how? The medical examiner’s report released several weeks later added even more gruesome details.

First, the time of death.

The examination determined that all three died sometime between 1990 and 1992.

They died there shortly after their disappearance.

Second, the cause of death of Matt and Brendan.

They were not shot.

They were not beaten to death.

The cause of death listed in the report was exhaustion and dehydration.

They were tied to beams and left to die slowly.

Third, the injuries sustained during their lifetime.

A 7 cm long indented fracture was found on Matthew Kelly’s skull.

The expert determined that the shape of the dent perfectly matched the shape of the butt of a Remington 7400 carbine found at the scene.

He was struck with tremendous force.

But the most chilling detail was the X-ray of Brendan How’s jaw.

His jaw was broken, and according to the expert’s conclusion, the fracture had begun to heal.

It was crooked, without medical attention, but bone callus had already begun to form.

This meant one thing.

Brendan How had been alive in that cabin long enough after the fracture.

Several weeks, perhaps a month.

The case was immediately reclassified from accidental death to double murder.

Now the investigators had a new picture.

Someone, presumably the man in camouflage, had kidnapped Matt and Brendan from their island.

He had transported them to the mainland, possibly in their own canoe, which he then sank or hid.

He had brought them to this abandoned cabin.

He beat them, breaking Brendan’s jaw and smashing Matt’s head with a rifle butt.

Then he tied them to the beams.

And here was the main question.

If he was their kidnapper, who killed him by smashing his skull? And why did he leave his captives to starve to death instead of just killing them? The discovery in that dilapidated hut in the fall of 2000 completely changed the case.

Investigators no longer had two missing tourists.

They had a triple murder scene.

Or so it seemed at first glance.

The case was immediately reopened.

Now the main question was not where are Matt and Brendan, but who is this third person and what happened here? The bodies of Matthew Kelly and Brendan How were identified by dental records.

But the third skeleton was a mystery.

He was wearing camouflage clothing, but there was no wallet or ID in his pockets.

He was a ghost.

The key to the mystery was a rusty Remington 7400 carbine lying next to him.

The weapon was in terrible condition.

10 years in a damp environment under a leaky roof had almost destroyed it.

But forensic scientists from the Minnesota State Laboratory achieved the nearly impossible.

They used X-ray techniques and acid etching to restore the serial number on the barrel.

That number led them to the sale of the weapon.

The carbine had been purchased in 1987 at a gun shop in Duth.

The buyer was identified.

He was a man whose name was well known to local rangers and some old-timers in St.

Louis County, but not to the police.

He was a Navy veteran who had served in Vietnam.

After being discharged on medical grounds, he returned to Minnesota, but was unable to reintegrate into society.

By the end of the 1980s, he had completely disappeared from the system.

He had no address and no official job.

Local residents knew him as a recluse, a mountain man.

He was known for his extremely paranoid behavior, distrust of the government, and hostility toward any outsiders whom he considered invaders on his territory.

He lived off the grid, moving through the woods and apparently using old abandoned structures such as this 1940s cabin as his bases.

And critically, he was an experienced sailor.

This perfectly explained the complex nautical knots that bound Matt and Brendan.

Knots that were impossible to untie with bare hands.

With this information, investigators were able to reconstruct the most likely and most terrifying chronology of events in September 1990.

It all starts with a campfire on Namakan Narrow’s Island.

Rangers discovered that the ashes were wet from rain that fell on Wednesday, September 5th.

Matt and Brendan were probably at camp that day.

The most plausible theory is that they either stumbled upon this man while fishing or hiking or he stumbled upon them.

Perhaps he approached their camp to steal supplies or more likely Matt and Brendan while exploring the rugged coastline accidentally discovered his illegal camp or traps on the mainland.

For a paranoid man who had been hiding from people for decades, this was tantamount to an invasion.

He couldn’t let them leave and report him to the authorities.

He captured them, probably threatening them with a rifle.

He forced them into their own Oldtown Ponobscot canoe.

That’s why the canoe wasn’t found on the island.

He fied them to the mainland.

Then he forced them to walk 5 1/2 m deep into the forest to his cabin.

This explains how they crossed such a distance without equipment.

Matt’s single shoe found by the water on the island remains a mystery.

Perhaps he lost it during the abduction.

Or perhaps the abductor forced him to remove his shoes to make escape more difficult and one shoe was simply left by the water.

Once in the cabin, the recluse was in complete control.

He beat them.

The injury to Matt’s skull from the butt of a rifle and Brendan’s broken jaw were not injuries sustained in a fight.

They were injuries inflicted to subdue them.

And then he tied them to the beams.

The most horrifying detail from the medical examiner’s report is Brendan How’s healing jaw.

A callous had begun to form.

That means Brendan was alive for weeks, maybe a month.

This refutes the theory that the kidnapper simply left them to die.

He kept them there.

He brought them water and food, enough to keep them from dying immediately.

They were his prisoners for weeks.

We will never know why.

Was it because of his mental state? Was he waiting for a ransom he couldn’t ask for? Or did he just enjoy the power? They were alive in that cabin until the end of September and perhaps until the beginning of October 1990.

And here we come to the end of this tragedy.

What happened to the kidnapper? His skull was smashed.

He was not tied up.

Investigators who examined the cabin in 2000 noted that the roof was not just rotten.

It had collapsed inward.

Several heavy support beams lay on the floor.

The official and most logical version is this.

The kidnapper was not killed.

At some point in late September or early October, he was in the hut, perhaps sleeping, perhaps bringing food to his captives.

The building was old.

The structure was rotten.

Due to rain or simply its own weight, one of the main roof beams gave way and collapsed.

It struck the hermit on the head, killing him instantly.

Matt Kelly and Brendan How, weakened, wounded, and tied to the walls, witnessed this.

Their captor, their tormentor, and their only source of water and food, was dead.

He lay on the floor just a few feet away, but as unreachable as freedom.

The nautical knots he had tied them with were too tight.

The nylon rope was impossible to break.

Forensic experts determined the cause of their deaths.

Exhaustion and dehydration.

They died a slow, agonizing death, locked in the hut with the body of their killer.

The case was closed.

It was classified as kidnapping and double murder committed by an unidentified person in official documents since his death prevented him from being charged whose death was ruled an accident.

This is a rare case in criminalistics when the perpetrator and the victims die in the same place but for completely different reasons.

The Oldtown Ponobscot canoe was never found.

The kidnapper probably sank it somewhere in the deep waters of Lake Namakan, taking the last piece of the story with him.

The forests of Minnesota kept this secret for 10 years, and only by chance did we learn the truth.

In November 1990, the case of Matthew Kelly and Brendan How was officially closed.

The St.

Louis County Coroner’s verdict, probable drowning.

Their bodies were never found.

But the evidence left at their campsite on Namokan Narrows Island told a very different story.

A story that had nothing to do with a sudden storm or a cap-sized canoe.

All the facts pointed to the fact that they did not leave the island of their own accord and that their disappearance was not an accident but something else.

It all began on Monday, September 3rd, 1990.

It was Labor Day.

Matt Kelly, 22, and Brendan How, 21, had just graduated from the University of Minnesota.

They were experienced hikers, not noviceses, and this was to be their last big trip before starting adult life.

They planned a week-long canoe trip through Voyagers National Park.

Voyagers National Park is not a place where you can walk along paved paths.

It is a maze.

Thousands of acres of water, rocks, and more than 500 islands scattered along the border with Canada.

In 1990, there was no cell phone service or GPS.

You registered with the rangers, picked up a map, a compass, and a walkie-talkie that only worked over short distances.

If you got into trouble, you were on your own.

That Monday, Matt and Brendan registered at the Ranger Station in Crane Lake at the southern tip of the park.

They left their car in the parking lot, provided their route, and obtained a camping permit.

Their main base was to be Namakan Narrows Island number 64.

It is a narrow strip of land 64 acres in size which essentially controls the narrow straight between Lake Namakan and Lake Kabatogama.

It was a remote, quiet place.

Their plan was simple, a week of fishing and hiking.

They were to return to the station at Crane Lake the following Saturday, September 8th, at p.m.

Saturday, September 8th.

had passed.

At , Matt and Brendan had not shown up.

This did not cause immediate panic.

Tourists are often late.

The wind could have blown them off course, or they might have simply decided to stay another night.

But by 700 p.m., as darkness began to fall, the ranger on duty at Crane Lake Station began to worry.

Their car was still in the parking lot.

At p.m., when it was almost dark, the rangers sent a patrol boat to check their campsite on Namakan Narrows Island.

The rangers arrived at the island at dusk.

The first thing they saw was a canoe.

It was an Oldtown Ponobscot 16, green in color, 16 ft long.

It was just lying on the sandy beach, untethered.

It had not been pulled out and secured as experienced tourists do, but it had not been carried away by the current either.

It was just lying at the water’s edge.

About 20 yard from the shore in a small grove stood their tent.

It was a blue Eureka Timberline, too.

The tent was fully assembled, the entrance zipper closed.

The rangers called out to Matt and Brendan.

There was no response.

They opened the tent.

Inside were two holofll sleeping bags, unrolled but looking unused.

Two backpacks lay nearby.

Inside the backpacks were their personal belongings.

Wallets, driver’s licenses, a change of clothes, and the keys to the car left in the parking lot at Crane Lake.

Everything was there.

Near the camp at a height of 4 1/2 m between two trees hung a Garcia food container.

It is a standard black barrel designed to protect food from bears.

It was untouched.

This immediately ruled out the possibility of a bear attack.

A bear would have gone for the food first.

The fire pit was cold.

When the rangers checked the ashes, they were completely wet, not just cool.

Heavy rain had fallen in the area on Thursday.

This meant that the fire in this pit had not been burning since at least last Wednesday, if not longer.

Matt and Brendan did not disappear on Saturday.

They disappeared sometime in the middle of the week.

No signs of a struggle, no traces of blood, no notes.

The camp was perfect, but empty.

The rangers found only two strange details.

There was an empty folders coffee can on a log by the fire.

And at the water’s edge, near where the canoe had been, there was a single boot.

It was a left hiking boot, size 11.

It was later identified as belonging to Matt Kelly.

And the strangest thing was that the boot was pointing toward the lake.

It was as if its owner had taken one last step and entered the water, but the other boot was nowhere to be found.

On Sunday, September 9th, a full-scale search and rescue operation began.

First, rangers combed the entire island, 64 acres.

Nothing.

On Monday, September 10th, boats from the St.

Louis County Sheriff’s Office joined the search.

They began combing the bottom around the island.

The water in Lake Namakan is dark and very cold.

Visibility is almost zero.

On Tuesday, September 11th, a Bell 206 helicopter was sent up.

It circled the island and surrounding waters for hours, looking for any bright spots, clothing, equipment, nothing.

On Wednesday, September 12th, divers arrived on the scene.

They dived in the area where the boot was found and in the area of the straight.

The bottom was littered with sunken trees.

It was slow and dangerous work and it yielded no results.

That same day on Wednesday, search dogs were brought in from Elely, Minnesota.

These were dogs trained to pick up scents.

They were given items from the sleeping bags to sniff.

The dogs picked up a scent from the tent, but it was weak.

They completely ignored the spot where the boot was found near the water.

Instead, they led the dog handlers across the entire island to its eastern tip.

It was a rocky cape that dropped down to the water, and there, at the roots of a large old birch tree, the trail ended.

The dog stopped, began to circle around in confusion, and lay down.

The dog handlers said that the trail had ended.

It did not go into the water.

It did not lead back into the forest.

It simply disappeared on that cape.

The active search continued for almost 2 weeks.

Neither Matt nor Brendan nor their equipment nor the second shoe were ever found.

In November 1990, when the lake began to freeze, the case was transferred to the archives.

The official cause was probable drowning.

This version did not satisfy anyone who had seen the scene.

If they had drowned after capsizing the canoe, why was the canoe on the shore? If they had drowned, why was their camp set up? And if they had both drowned, who had placed Matt’s shoe with the toe pointing toward the water? For 10 years, Matt and Brendan’s families lived with this version.

For 10 years, they were considered missing, presumed drowned.

Until an autumn day on September 11th, 2000 changed everything.

10 years.

For 10 years, the case of Matthew Kelly and Brendan How sat in the St.

Louis County Archives.

The official verdict of probable drowning satisfied no one, but there was nothing to challenge it with.

For 10 years, their families lived without answers.

Matt’s car remained in the parking lot at Crane Lake until his father finally took it away.

A size 11 shoe found near the water and an Oldtown Ponobscot canoe were the only clues, and they revealed nothing.

For 10 years, the forest and the water kept their secret.

Then on September 11th, 2000, that secret was revealed in the most brutal way.

That day, a crew of loggers from Wire Hooser was working a few miles north of Lake Namakan.

They weren’t tourists.

They were professionals cutting a new trail for timber transport in the dense, impenetrable forest.

Their site was about 5 1/2 miles north of Namakan Narrow’s Island.

To be clear, that’s 5 1/2 miles in a straight line through swamps and impenetrable thicket far from the water.

One of the bulldozer operators clearing debris stumbled upon a structure.

It was an old hunting cabin sunk into the ground.

Judging by its construction, it had been built back in the 1940s.

It had long since fallen into disrepair.

The shingle roof had collapsed inward.

The log walls were covered with mold.

The loggers approached to make sure there were no vagrants or possibly dead animals inside.

What they saw inside prompted them to immediately contact the sheriff’s office.

Inside the half-colapsed hut in the dim light, among the rubbish and fallen beams, were human remains.

These were not just remains.

It was a place of execution.

Two skeletons were tied to the central support beams of the roof.

They were tied not with rope, but with thick 10 mm nylon rope.

Judging by the preserved fragments, they had once been suspended so that they barely touched the floor.

Both had their hands tied behind their backs.

Their legs were also tied together and tied to the lower beams of the wall.

Forensic experts who arrived at the scene noted the knots.

These were complex nautical knots tied with great force.

It was impossible to cut them, so they had to be sawed off.

The clothing on the remains had almost completely decayed, but fragments remained.

These were the remains of Patagonia fleece jackets and Levis’s jeans.

These were models that were popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

This was the first clue.

Later, dental records would confirm that these were Matthew Kelly and Brendan How.

But they weren’t alone.

In the far corner of the cabin, behind an overturned table, lay a third skeleton.

This man was dressed in the remains of a camouflage uniform.

Unlike Matt and Brendan, he was not tied up.

He was lying on his back, and the entire front of his skull had been smashed in.

A carbine lay in the mud next to his right hand.

The weapon was so rusted that there were holes through the barrel, but the model was identifiable.

It was a Remington semi-automatic carbine, model 7400.

The crime scene investigation team arrived.

The scene was horrific.

It didn’t look like a drug deal gone wrong or a random murder.

It was methodical.

The case of the drowned students was immediately pulled from the archives.

Now, the investigators had three bodies and a cabin 5 and a half miles from the students last known location.

But how did they get there? Their canoe, the old town Ponobscot, was never found.

Not on the island, not on the mainland.

There were no signs that they had crossed 5 1/2 miles of rugged forest on foot.

It appeared that they had been brought to this cabin.

But by whom and how? The medical examiner’s report released several weeks later added even more gruesome details.

First, the time of death.

The examination determined that all three died sometime between 1990 and 1992.

They died there shortly after their disappearance.

Second, the cause of death of Matt and Brendan.

They were not shot.

They were not beaten to death.

The cause of death listed in the report was exhaustion and dehydration.

They were tied to beams and left to die slowly.

Third, the injuries sustained during their lifetime.

A 7 cm long indented fracture was found on Matthew Kelly’s skull.

The expert determined that the shape of the dent perfectly matched the shape of the butt of a Remington 7400 carbine found at the scene.

He was struck with tremendous force.

But the most chilling detail was the X-ray of Brendan How’s jaw.

His jaw was broken, and according to the expert’s conclusion, the fracture had begun to heal.

It was crooked, without medical attention, but bone callus had already begun to form.

This meant one thing.

Brendan How had been alive in that cabin long enough after the fracture.

Several weeks, perhaps a month.

The case was immediately reclassified from accidental death to double murder.

Now the investigators had a new picture.

Someone, presumably the man in camouflage, had kidnapped Matt and Brendan from their island.

He had transported them to the mainland, possibly in their own canoe, which he then sank or hid.

He had brought them to this abandoned cabin.

He beat them, breaking Brendan’s jaw and smashing Matt’s head with a rifle butt.

Then he tied them to the beams.

And here was the main question.

If he was their kidnapper, who killed him by smashing his skull? And why did he leave his captives to starve to death instead of just killing them? The discovery in that dilapidated hut in the fall of 2000 completely changed the case.

Investigators no longer had two missing tourists.

They had a triple murder scene.

Or so it seemed at first glance.

The case was immediately reopened.

Now the main question was not where are Matt and Brendan, but who is this third person and what happened here? The bodies of Matthew Kelly and Brendan How were identified by dental records.

But the third skeleton was a mystery.

He was wearing camouflage clothing, but there was no wallet or ID in his pockets.

He was a ghost.

The key to the mystery was a rusty Remington 7400 carbine lying next to him.

The weapon was in terrible condition.

10 years in a damp environment under a leaky roof had almost destroyed it.

But forensic scientists from the Minnesota State Laboratory achieved the nearly impossible.

They used X-ray techniques and acid etching to restore the serial number on the barrel.

That number led them to the sale of the weapon.

The carbine had been purchased in 1987 at a gun shop in Duth.

The buyer was identified.

He was a man whose name was well known to local rangers and some old-timers in St.

Louis County, but not to the police.

He was a Navy veteran who had served in Vietnam.

After being discharged on medical grounds, he returned to Minnesota, but was unable to reintegrate into society.

By the end of the 1980s, he had completely disappeared from the system.

He had no address and no official job.

Local residents knew him as a recluse, a mountain man.

He was known for his extremely paranoid behavior, distrust of the government, and hostility toward any outsiders whom he considered invaders on his territory.

He lived off the grid, moving through the woods and apparently using old abandoned structures such as this 1940s cabin as his bases.

And critically, he was an experienced sailor.

This perfectly explained the complex nautical knots that bound Matt and Brendan.

Knots that were impossible to untie with bare hands.

With this information, investigators were able to reconstruct the most likely and most terrifying chronology of events in September 1990.

It all starts with a campfire on Namakan Narrow’s Island.

Rangers discovered that the ashes were wet from rain that fell on Wednesday, September 5th.

Matt and Brendan were probably at camp that day.

The most plausible theory is that they either stumbled upon this man while fishing or hiking or he stumbled upon them.

Perhaps he approached their camp to steal supplies or more likely Matt and Brendan while exploring the rugged coastline accidentally discovered his illegal camp or traps on the mainland.

For a paranoid man who had been hiding from people for decades, this was tantamount to an invasion.

He couldn’t let them leave and report him to the authorities.

He captured them, probably threatening them with a rifle.

He forced them into their own Oldtown Ponobscot canoe.

That’s why the canoe wasn’t found on the island.

He fied them to the mainland.

Then he forced them to walk 5 1/2 m deep into the forest to his cabin.

This explains how they crossed such a distance without equipment.

Matt’s single shoe found by the water on the island remains a mystery.

Perhaps he lost it during the abduction.

Or perhaps the abductor forced him to remove his shoes to make escape more difficult and one shoe was simply left by the water.

Once in the cabin, the recluse was in complete control.

He beat them.

The injury to Matt’s skull from the butt of a rifle and Brendan’s broken jaw were not injuries sustained in a fight.

They were injuries inflicted to subdue them.

And then he tied them to the beams.

The most horrifying detail from the medical examiner’s report is Brendan How’s healing jaw.

A callous had begun to form.

That means Brendan was alive for weeks, maybe a month.

This refutes the theory that the kidnapper simply left them to die.

He kept them there.

He brought them water and food, enough to keep them from dying immediately.

They were his prisoners for weeks.

We will never know why.

Was it because of his mental state? Was he waiting for a ransom he couldn’t ask for? Or did he just enjoy the power? They were alive in that cabin until the end of September and perhaps until the beginning of October 1990.

And here we come to the end of this tragedy.

What happened to the kidnapper? His skull was smashed.

He was not tied up.

Investigators who examined the cabin in 2000 noted that the roof was not just rotten.

It had collapsed inward.

Several heavy support beams lay on the floor.

The official and most logical version is this.

The kidnapper was not killed.

At some point in late September or early October, he was in the hut, perhaps sleeping, perhaps bringing food to his captives.

The building was old.

The structure was rotten.

Due to rain or simply its own weight, one of the main roof beams gave way and collapsed.

It struck the hermit on the head, killing him instantly.

Matt Kelly and Brendan How, weakened, wounded, and tied to the walls, witnessed this.

Their captor, their tormentor, and their only source of water and food, was dead.

He lay on the floor just a few feet away, but as unreachable as freedom.

The nautical knots he had tied them with were too tight.

The nylon rope was impossible to break.

Forensic experts determined the cause of their deaths.

Exhaustion and dehydration.

They died a slow, agonizing death, locked in the hut with the body of their killer.

The case was closed.

It was classified as kidnapping and double murder committed by an unidentified person in official documents since his death prevented him from being charged whose death was ruled an accident.

This is a rare case in criminalistics when the perpetrator and the victims die in the same place but for completely different reasons.

The Oldtown Ponobscot canoe was never found.

The kidnapper probably sank it somewhere in the deep waters of Lake Namakan, taking the last piece of the story with him.

The forests of Minnesota kept this secret for 10 years, and only by chance did we learn the truth.

News

Six Cousins Vanished in a West Texas Canyon in 1996 — 29 Years Later the FBI Found the Evidence

In the summer of 1996, six cousins ventured into the vast canyons of West Texas. They were last seen at…

Sisters Vanished on Family Picnic—11 Years Later, Treasure Hunter Finds Clues Near Ancient Oak

At the height of a gentle North Carolina summer the Morrison family’s annual getaway had unfolded just like the many…

Seven Kids Vanished from Texas Campfire in 2006 — What FBI Found Shocked Everyone

In the summer of 2006, a thunderstorm tore through a rural Texas campground. And when the storm cleared, seven children…

Family Vanished from Stillwater Lake Texas in 1995 — 27 Years Later FBI Found Box with Clothes

In the summer of 1995, the Whitlock family vanished without a trace during their weekend retreat at Stillwater Lake. Their…

Family Vanished from Stillwater Lake Texas in 1995 — 27 Years Later FBI Found Box with Clothes

In the summer of 1995, the Whitlock family vanished without a trace during their weekend retreat at Stillwater Lake. Their…

SOLVED: Arizona Cold Case | Robert Williams, 9 Months Old | Missing Boy Found Alive After 54 Years

54 years ago, a 9-month-old baby boy vanished from a quiet neighborhood in Arizona, disappearing without a trace, leaving his…

End of content

No more pages to load