In June of 2000, 19-year-old Drew Ryder and his 18-year-old friend Frank Puit drove deep into the Wyoming wilderness for a weekend fishing trip.

They vanished within hours of reaching a remote river access point.

Three months passed and when a surveyor named Dale Jensen cleared a stack of firewood outside an old hunting cabin to check a property line, little did he know that within minutes he would pry open a hidden trap door and find two boys chained to chairs with white cloth gags tied over their mouths.

It was the beginning of a case that would forever change the way the locals viewed the danger of the Wyoming back country.

Drew Ryder had known Frank Puit since middle school.

the kind of friendship forged through shared detentions, late night drives, and an unspoken understanding that neither of them quite fit the mold of their small Wyoming town.

By the summer of 2000, Drew was 19, working part-time at his uncle’s hardware store, while Frank, 18, and fresh out of high school, was killing time before fall semester at community college.

They both needed to get out to breathe air that didn’t smell like obligation and routine.

The fishing trip was Frank’s idea.

He’d heard about a stretch of the Graze River accessible only by a rough dirt road that wounded deep into the Bridgetger Teton National Forest, far from the marked campgrounds and weekend warriors.

Drew didn’t need much convincing.

On Thursday afternoon, June 15th, they loaded Drew’s faded blue Ford Ranger with gear, rods, a cooler, sleeping bags, and a disposable camera Frank had bought at the gas station.

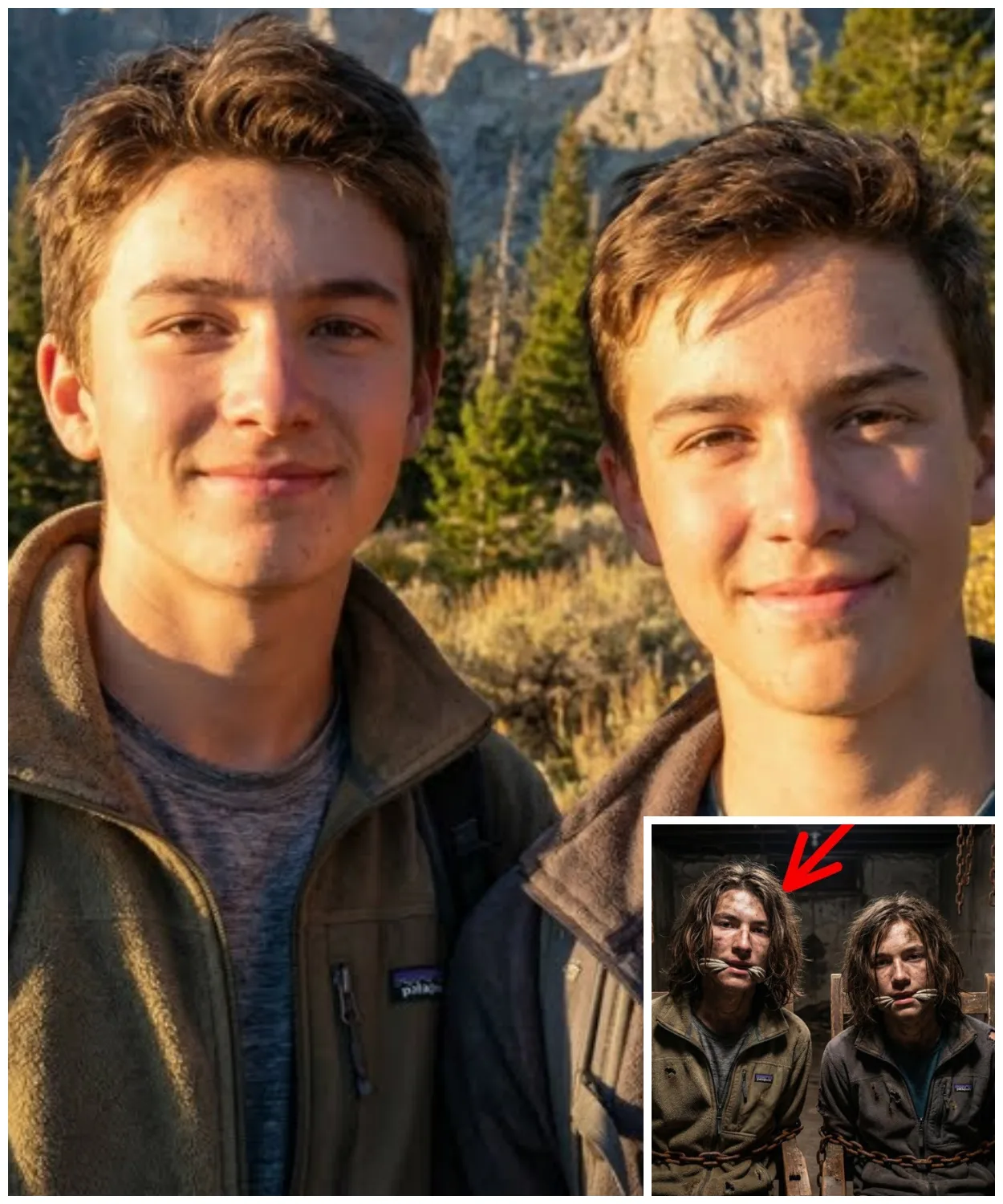

Before they left the parking lot, Frank held the camera at arms length and snapped a photo of them both grinning in the cab, Drew’s hand on the wheel, the mountains visible through the windshield behind them.

It was the last image anyone would have of them looking like themselves.

They drove north through Afton, then turned onto Forest Road 138, a name that existed only on outdated maps.

The pavement gave way to gravel, then to ruted dirt that jarred their spines with every pothole.

Drew’s truck handled it fine.

They passed a handful of dispersed campsites, all empty until even those disappeared.

By late afternoon, they reached the access point Frank had marked on his map.

A pull out near a bend in the river where the water ran cold and clear over smooth stones.

They parked beneath a stand of lodgepole pines, the truck’s engine ticking as it cooled in the mountain silence.

A Forest Service employee later reported seeing a blue pickup truck in that area on Friday morning, though he hadn’t approached it.

On Sunday evening, when Drew failed to call his mother as promised, she waited an hour before calling Frank’s parents.

By Monday morning, both families had driven to the ranger station in Alpine.

The search began that afternoon.

Searchers found the truck exactly where Drew had parked it, doors locked, keys missing.

The gear was gone, which suggested the boys had made it to their campsite.

But there was no campsite, no fire ring, no trampled grass, no sign of two teenagers anywhere along that stretch of river.

The search expanded to a 3m radius.

Then five helicopters swept the ridges.

Dive teams checked the deeper pools.

For two weeks, over 60 volunteers combed the forest, calling names that were swallowed whole by the wind and the pines.

By early July, the search was scaled back to periodic checks.

Drew Ryder and Frank Puit had simply vanished into the vast indifference of the Wyoming wilderness.

The locked truck sat in the forest like a puzzle with missing pieces.

Sheriff’s Deputy Carl Montrose was the first law enforcement officer to reach it on Monday afternoon, June 19th, 4 days after Drew and Frank had driven into the wilderness.

He circled the blue Ford Ranger twice, noting the undisturbed dust on the hood, the windows rolled up tight, the doors secured.

He kept his hands against the glass and peered inside.

Empty soda cans on the dashboard.

A watted gas station receipt.

A faded air freshener hanging from the rear view mirror.

Nothing that suggested panic or struggle.

Just the ordinary debris of two teenagers on a fishing trip.

The keys were gone.

Drew’s mother confirmed he always kept them on a carabiner clipped to his belt loop.

The fact that the truck was locked suggested the boys had taken their gear and walked away with purpose, with intention, but walked where.

The river was 30 yards downhill through the trees, accessible and calm.

Search and rescue coordinator Linda Voss arrived by Tuesday morning with 12 volunteers and two German shepherds trained in wilderness tracking.

The dogs circled the truck, noses low, and then moved toward the river.

They lost the scent at the W’s edge.

By Wednesday, the operation had grown to over 40 people.

They divided the area into grid sections, each team responsible for a/4 mile square of forest.

They searched the obvious dangers first.

The steep embankments where a hiker might lose footing.

The deeper channels where a swimmer could be pulled under, the talis slopes where a twisted ankle could turn fatal.

They found nothing.

No clothing snagged on branches.

No footprints preserved in the mud near the riverbank.

No trampled vegetation indicating a campsite.

It was as if Drew and Frank had evaporated the moment they stepped out of the truck.

The terrain itself seemed to resist the search.

The forest was dense with lodgepole pine and Douglas fur.

The understory choked with deadfall and low brush.

Visibility extended only 20 or 30 feet in any direction before the trees swallowed everything.

The volunteers called out the boy’s names every few minutes, their voices strange and flat in the open air, absorbed by the mountains before an echo could return.

More than one searcher later described the silence as wrong, not peaceful, but oppressive, as though the wilderness itself was deliberately withholding answers.

On Thursday, a helicopter from the Wyoming National Guard joined the effort.

Equipped with thermal imaging cameras, the crew flew systematic passes over a 15 square mile area, scanning for heat signatures that might indicate a person injured or lost lying beneath the canopy.

They found elk.

They found a black bear saw with two cubs.

They found nothing human.

Sheriff Tom Hackett stood near the command tent that evening, arms folded, staring at the topographic map spread across a folding table.

He’d worked search and rescue in Lincoln County for 19 years.

He’d found lost hikers, recovered drowning victims, located the wreckage of a small plane that had gone down in a snowstorm.

He knew how to read the wilderness, but this felt different.

This felt like the mountains had taken the boys on purpose.

By the second week, the K9 teams had expanded their search to cover over 20 m of forest and river corridor.

They checked abandoned hunting cabins, old mines, rocklide debris fields.

Divers in dry suits swept the deeper pools downstream, working in zero visibility through the silt.

A botonist volunteer noted that the vegetation around the truck showed no signs of recent disturbance, no broken stems or crushed wild flowers that would indicate two people hauling fishing gear toward the water.

The official search was scaled back on July 3rd.

The case remained open, but the daily operations ceased.

Drew Ryder and Frank Puit were reclassified as missing persons, their names added to a database that stretched across the state.

The wilderness had swallowed them completely, and in the vast unsettling silence of the Wyoming back country, it offered no explanation, no mercy, and no clues.

September arrived cold and early in the Wyoming high country.

The Aspens had already begun their turn to gold, and morning frost lingered in the shadows until nearly noon.

Dale Jensen had been working the remote property lines northeast of the Grace River since early August, contracted by a land management company to verify boundaries before a potential sale.

The work was solitary and methodical, exactly the way he preferred it.

He spent his days moving through unmarked forest with a GPS unit, a transit, and a notebook, comparing coordinates to century old survey markers that were often nothing more than rusted iron pins driven into stones.

On the morning of September 12th, he was working a section he’d marked as low priority federal land adjacent to a handful of old mining claims that had been abandoned since the 1950s.

The terrain was rough, a series of low ridges covered in second growth pine and scattered with granite outcroppings.

He wasn’t expecting to find anything of note.

Certainly not a cabin.

He spotted it just after , set back in a natural depression about 40 yards off the line he was walking.

At first glance, it looked like a dozen other forgotten structures scattered throughout the back country.

Weathered logs, a steeply pitched roof designed to shed snow, a single window facing south.

But as Dale approached, his professional eye caught the inconsistencies.

The logs had been recently treated with a dark stain that still held a faint sheen.

The window glass was intact, not cracked or missing like most abandoned buildings.

And the door, a heavy slab of plankked wood, was secured with a modern padlock, the steel bright and free of rust.

Dale stopped 20 ft away, his instinct prickling.

Hunters sometimes restored old cabins for seasonal use, but this was miles from any legal access road, and the hunting season hadn’t opened yet.

He circled the structure slowly.

The roof was sound, the chinking between the logs recently repaired.

On the east side of the cabin, someone had stacked firewood with almost obsessive precision.

A wall of split pine and fur 4 ft high and 12 ft long.

Each piece cut to identical length.

The rows so tight and uniform they looked machine-made.

It was too much wood for a weekend camp.

Too much care for a place this remote.

Dale pulled out his notebook and jotted down the coordinates, making a note to check the claim records when he got back to town.

As he wrote, a gust of wind moved through the trees, and he heard something.

A faint metallic sound like a chain shifting.

He looked up, listening, but it didn’t repeat.

Probably just a loose piece of roofing tin, he thought.

But the sound had come from the ground, not the roof.

He moved toward the wood pile, studying the dirt around its base.

The earth looked slightly compressed, unnaturally level for forest ground.

He crouched and noticed that the soil beneath the bottom row of wood was darker, damper, as if something beneath was preventing proper drainage.

He pulled a piece of wood from the bottom of the stack.

Then another.

On the third piece, he saw it.

A slight depression in the dirt, maybe 2 in deep and perfectly rectangular, too uniform to be natural.

Dale cleared more wood, working faster now.

his pulse starting to climb.

After a few minutes, he’d exposed a section of ground about 4 ft square.

The depression was clearer now, and at the far edge, partially buried in loose soil, he saw a small iron ring, no bigger than a drawer pull, the metal dark with age, but free of the oxidation that should have covered something buried in the earth.

He brushed the dirt away from the ring with his fingers.

It was attached to something solid beneath the surface.

Dale gripped it and pulled.

The ring didn’t budge, but the ground around it shifted slightly, and a hairline crack appeared in the soil, forming the outline of a trapdo.

Dale Jensen had spent 30 years working in remote places where cell phone coverage was a fantasy and the nearest human being might be 10 mi away.

He’d learned to trust his gut, and right now his gut was telling him to stop, to walk back to his truck, to call the county sheriff from the ranger station in Alpine.

But his hands were already pulling at the iron ring.

his boots bracing against the earth as he hauled upward.

The trapoor resisted, sealed by three months of settled dirt and its own weight, then gave way with a sudden crack that sent Dale stumbling backward.

The door fell open, revealing a square of darkness, and a smell that hit him like a fist, damp concrete, human waste, and something else, something sweet and wrong that he couldn’t identify.

A set of rough wooden steps descended into the black.

Dale’s breath came short and fast.

He pulled the mag light from his belt and clicked it on, the beam cutting down into the hole.

The stairs ended after 8 ft.

The basement was small, maybe 10 ft by 12.

The walls poured concrete that wept moisture and dark streaks.

The floor was concrete, too, stained and uneven.

Dale’s lights swept left, then right, and then stopped.

Two figures sat motionless in the center of the room, each secured to a wooden chair.

They were so still that for a horrible moment Dale thought they were dead that he’d opened a tomb instead of a prison.

Then one of them moved just barely, a slight turn of the head toward the sudden intrusion of light.

The movement was slow, uncertain, as if the body had forgotten how.

Dale descended three steps, his hand gripping the frame of the trapoor.

The beam of his flashlight shook.

The young men were skeletal, their clothes hanging off frames that had been starved down to bone and tendon.

Their jeans were torn and filthy, their t-shirts stained beyond recognition.

Their wrists were secured to the chair arms with heavy chains, the kind used for towing vehicles, the links fastened with padlocks.

Their ankles were chained as well, fixed to the front legs of the chairs so tightly there was no possibility of standing.

But it was their faces that made Dale’s stomach twist.

Each boy had a strip of white cloth tied across his mouth, knotted tightly at the back of his head.

The fabric had once been clean, but was now gray with dirt and sweat, stretched taut across their lips, and cutting into the corners of their mouths.

Their eyes were open, wide, and glassy in the flashlight beam, reflecting the light like the eyes of animals caught on a roadside at night.

Dale’s voice came out as a rasp.

Jesus Christ, can you hear me? The boy on the left blinked.

It was the only acknowledgement.

Dale came down the remaining steps, his boots loud on the concrete.

He could see them more clearly now.

The one on the left had dark hair matted to his skull, his face covered in patchy stubble.

The one on the right was younger looking, his hair lighter, his cheeks hollow.

Both had pressure sores visible on their forearms where the chains had rested for weeks.

Their breathing was shallow, barely visible.

I’m going to get you out, Dale said, though he had no idea how.

The chains were thick, the padlocks solid.

He didn’t have bolt cutters.

He didn’t have anything.

He moved closer to the boy on the right and reached toward the gag.

The boy flinched, a full body recoil that rattled the chains.

Dale froze.

“It’s okay,” he said quietly.

“I’m not going to hurt you.

I’m getting help.” The boy stared at him, unblinking, his breath hissing faintly through his nose.

Dale’s hand hovered near the white cloth, then pulled back.

He turned and climbed the stairs as fast as his shaking legs would carry him, emerging into the cold September air.

He ran.

Dale Jensen’s hands shook so violently that he dropped his radio twice before managing to key the transmit button.

He was 50 yards from the cabin, leaning against a pine tree, forcing air into his lungs.

The dispatcher at the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Office answered with her usual practiced calm, but that calm fractured the moment Dale stammered out what he’d found.

She told him to stay on the line.

She told him help was coming.

She told him not to go back into the basement.

He went back anyway.

He couldn’t leave them in the dark.

He descended the stairs again, slower this time, and wedged the trap door open with a chunk of firewood so daylight could spill into the hole.

The two young men hadn’t moved.

Dale stood at the bottom of the steps, 3 ft away, and spoke to them in a low, steady voice.

He told them his name.

He told them the police were coming.

He told them they were going to be okay, even though he wasn’t sure that was true.

Neither boy responded.

Their eyes tracked him when he moved, but that was all.

The first sheriff’s deputy arrived 28 minutes later, his patrol vehicle screaming up the access road as far as the terrain allowed before he continued on foot.

Deputy Carl Montro had been one of the primary responders when Drew and Frank first disappeared.

He took one look into the basement and immediately radioed for additional units for medical evacuation for Detective Patricia Hayes.

His voice, usually measured and professional, carried an edge that made the dispatcher ask him to repeat himself.

Within an hour, the remote clearing around the cabin had become a controlled crime scene.

Yellow tape cordoned off a perimeter.

Two paramedics from the Alpine Ambulance Service descended into the basement with medical kits and a portable stretcher, moving carefully to avoid disturbing potential evidence.

Detective Hayes arrived in a county SUV, her face set in the hard, unreadable mask she wore at every major scene.

She photographed the basement from the top of the stairs before allowing anyone to touch the boys.

The paramedics assessed the victims without removing the chains.

Both young men were severely dehydrated, their pulses weak and rapid.

Their skin was pale and clammy, their body temperatures dangerously low.

One paramedic, a woman named Laura Pittz, tried to remove the gag from the boy on the right.

He made a sound, a muffled guttural noise of pure panic, and thrashed against the chains hard enough that the chair legs scraped across the concrete.

Laura pulled her hand back immediately.

“It’s okay,” she said softly.

“We’re not going to hurt you.

We’re going to get these off, but we need to cut the chains first.

Do you understand?” The boy stared at her.

After a long moment, he gave the smallest nod.

A maintenance crew from the county road department brought heavyduty bolt cutters and an angle grinder.

The noise of the grinder in the enclosed concrete space was deafening, a high metallic scream that made both boys flinch violently.

The crew worked as quickly as possible, cutting through the chain links at the wrists first, then the ankles.

When the first chain fell away from the boy on the left, his arm dropped limply to his side.

He didn’t have the strength to hold it up.

The muscles had atrophied after 3 months of immobility.

It took 40 minutes to free them both.

The moment the last chain was cut, the paramedics moved in with warming blankets and four kits.

They worked gently, explaining every movement before they made it.

When Laura finally reached for the gag on the boy on the right, she paused and made eye contact.

I’m going to take this off now.

Okay.

He didn’t nod this time.

He just closed his eyes.

She untied the knot at the back of his head, her fingers working carefully through the matted hair.

The cloth had been tied so tightly for so long that it had left deep indentations in his cheeks.

When she pulled it away, his jaw didn’t move.

His mouth stayed closed, his lips pressed together as if the gag were still in place.

Laura checked his airway, then offered him water from a bottle with a straw.

He didn’t drink.

The boy on the left allowed his gag to be removed without resistance, but his reaction was the same.

His mouth remained shut, his expression blank.

One of the paramedics noted in his report that both victims appeared to have forgotten how to open their mouths voluntarily.

They were carried out of the basement on stretchers, blinking against the September sunlight like men emerging from a cave.

A medical helicopter had landed in a clearing a/4 mile away.

The rotors still spinning.

The plan was to airlift them directly to the regional hospital in Idaho Falls where a trauma team was already standing by.

But before they were loaded, Detective Hayes approached the stretcher carrying the boy on the right.

She crouched beside him, her voice low.

Can you tell me your name? He stared at the sky.

His lips moved, but no sound came out.

Ace tried again.

Do you know where you are? Nothing.

She looked at the paramedic.

Can he speak? I don’t know, Laura said quietly.

Physically, there’s no reason he shouldn’t be able to, but he’s not trying.

The same was true for the other boy.

Both were conscious, both responsive to physical stimuli, but neither made any attempt to communicate.

When a deputy leaned over the first stretcher and said, “You’re safe now.

It’s over.” The boy didn’t react at all.

His eyes were open, but he was looking at something far beyond the trees and the uniforms and the people trying to help him.

The helicopter lifted off at p.m.

, carrying both victims toward medical care and the long, uncertain process of recovery.

Back at the cabin, Detective Hayes stood at the edge of the open trap door, staring down into the basement.

The two wooden chairs sat empty in the center of the concrete floor.

The cut chains coiled at their feet like dead snakes.

On the floor between them, she noticed something she hadn’t seen before.

Two long grooves in the concrete worn smooth as if the legs of the chairs had been dragged back and forth, back and forth in the same place for months.

Detective Patricia Hayes had worked homicides, domestic violence cases, and methamphetamine busts across Lincoln County for 14 years, but she had never worked a case that felt like this.

The cabin sat in its clearing like a carefully prepared stage, every element deliberate, every detail planned.

By the evening of September 12th, the crime scene had been secured with portable lights and a generator, casting harsh white illumination across the structure and the forest around it.

Hayes directed a team of five investigators, two evidence technicians from the state crime lab, and a forensic analyst from Cheyenne who specialized in construction and materials.

The cabin itself was registered to no one.

A title search revealed that the land had been part of a failed mining claim in 1952, reverting to federal control when the claim lapsed.

There was no record of the structure in any county database, no building permits, no tax records.

It existed in a legal and bureaucratic void, which Haye suspected was exactly the point.

Whoever had renovated it had done so invisibly, using the wilderness and the absence of oversight as camouflage.

The forensic team began with the basement.

The concrete walls and floor were not original to the structure.

A core sample revealed that the concrete had been poured within the last 5 years.

The aggregate and chemical composition consistent with commercial-grade mix available at any hardware store in the region.

The walls had been reinforced with rebar visible in places where the concrete had cracked slightly from ground settling.

This wasn’t a root seller dug by homesteaders.

This was a deliberate construction built to contain.

The chairs were analyzed next.

Both were handmade, constructed from rough cut pine with joinery that suggested basic carpentry skills, but no professional training.

What stood out was their weight.

Each chair was far heavier than necessary, reinforced with internal bracing that made them nearly impossible to tip or break.

The evidence technician, a thin man named Gordon Ree, pointed out the wear patterns on the legs.

These chairs have been here for months, maybe longer.

See the way the concrete is worn smooth right here.

That’s from repetitive movement, probably the victim shifting their weight.

But look at this.

He directed Hayes’s flashlight to four faint marks on the floor, each about the size of a tennis ball, positioned exactly where the chair legs would rest.

The marks were white, the remnant of some kind of paint or chalk.

Whoever set this up marked the position of the chairs before the victims were ever brought here, Ree said.

He knew exactly where he wanted them.

This wasn’t improvised.

Hayes crouched and studied the marks.

They were partially worn away, but still visible.

Ghosts of a plan executed with precision.

She had the entire floor photographed under different lighting conditions, including UV.

The ultraviolet light revealed additional markings, faint lines that formed a grid pattern, suggesting the perpetrator had measured and planned the layout of the space before pouring the concrete.

The chains themselves were standard hardware store stock galvanized steel with a 3,000lb tensil strength overkill for restraining two teenage boys.

The padlocks were identical, all from the same manufacturer, likely purchased in a multiack.

Hayes had a deputy canvas every hardware and farm supply store within a 100m radius, asking about bulk purchases of chain and locks.

The canvas yielded nothing useful.

The items were too common, sold to ranchers and contractors every day.

Upstairs, the cabin revealed more about the perpetrators mindset.

The main room contained a cot with a thin mattress, a propane camp stove, and a plastic cooler.

Inside the cooler, investigators found empty jugs that had once contained a nutritional supplement drink, the kind used in hospitals for patients unable to eat solid food.

The labels had been peeled off, but the residue was enough for analysis.

Hayes theorized this was what the victims had been fed, poured directly into their mouths while gagged, just enough to keep them alive.

A notebook was found on a wooden shelf, its pages filled with handwritten entries.

The writing was block print, methodical and legible, but the content was chilling in its benality.

The entries were schedules, times and dates recorded in military format 0600 check subjects 1,800 feeding 2,100 secure site.

The entries spanned from mid June to early September, ending abruptly on September 9th, 3 days before Dale Jensen discovered the trapoor.

There were no names, no personal reflections, nothing that revealed emotion or motive, just logistics.

The FBI’s behavioral analysis unit sent two agents to the site on September 15th.

Special agent Carla Dennison had worked abduction cases across the mountain west for a decade, and her assessment was delivered with clinical precision.

This offender is highly organized and patient, she told Hayes during a briefing in the makeshift command tent.

The construction of the basement alone would have required multiple trips over weeks or months, carrying materials into a remote area without attracting attention.

He understands the terrain.

He knows how to move through it without being seen.

Dennis reviewed the photographs of the basement and the notebook.

The use of the gags is significant.

He didn’t just want them restrained.

He wanted them silent.

Complete control over their ability to communicate even with each other.

That’s psychological domination.

The remoteness of the location served a dual purpose.

It concealed the crime, but it also reinforced the victim’s helplessness.

Even if they had escaped the basement, they were miles from anything.

The wilderness was part of the prison.

Hayes asked the question that had been gnawing at her since the discovery.

Why did he stop? Why leave them alive? Dennison considered this.

He may have been spooked by something.

a hunter or hiker getting too close.

Or he may have simply completed whatever psychological need this fulfilled.

Some offenders operate on cycles.

They satisfy an urge then withdraw.

She paused.

Or he’s planning to come back.

The investigation expanded to include a review of everyone who had purchased property, filed mining claims, or held hunting permits in the area over the past decade.

The list contained over 300 names.

Cross-referencing against individuals with construction skills, carpentry experience, or forestry backgrounds narrowed it to 74.

None had prior records.

None raised immediate red flags.

The perpetrator had left behind a meticulously constructed prison, a detailed schedule, and two barely living victims.

But he had left no fingerprints, no DNA, no mistakes.

Drew Ryder and Frank Puit spent 11 days in the trauma unit at Eastern Idaho Regional Medical Center before they could speak in more than whispers.

The physical recovery was documented in charts filled with clinical terms.

Severe malnutrition, muscle atrophy, dehydration, infected pressure ulcers, but the psychological damage resisted diagnosis.

Both boys were plagued by night terrors.

Both refused to be alone in enclosed spaces.

Drew would wake screaming if a nurse closed his room door completely.

Frank hadn’t made eye contact with anyone, including his own parents.

For the first week, Detective Patricia Hayes waited.

She coordinated with the hospital’s trauma psychologist, a woman named Dr.

Ellen Marsh, who specialized in abduction cases, and together they determined that September 23rd would be the first attempt at a formal interview.

Hayes arrived at the hospital just after breakfast.

Drew had been moved to a private room with a window overlooking the parking lot.

He sat in a chair beside the bed, dressed in sweatpants and a hospitalissue shirt that hung loose on his frame.

His mother sat nearby, her hand resting on his shoulder.

Hayes introduced herself, though Drew had seen her twice before during brief welfare checks.

She pulled a chair close but not too close, maintaining space.

“I know this is hard,” she said quietly.

But I need to understand what happened to you.

Can you tell me about the day you disappeared? Drews hands were folded in his lap.

He stared at them for a long time before speaking.

His voice was horse barely above a whisper.

We were setting up camp near the truck.

Frank was getting the rods out of the bed.

What time was this? Maybe in the afternoon.

We just gotten there.

And then Drew’s jaw tightened.

He came out of the trees.

I didn’t hear him.

I didn’t hear anything until Frank made this sound like he’d been hit.

I turned around and there was a man standing behind him.

He had Frank’s arm twisted behind his back.

He had a gun.

Ace made a note.

Can you describe him? He was wearing a ski mask.

What? The kind that covers everything except the eyes.

He was tall, maybe 6 feet, wearing jeans and a dark jacket.

Gloves.

Drew’s voice wavered.

He didn’t say anything, not a word.

He just pointed the gun at me and motioned for me to come over.

I thought he stopped his breath catching.

I thought he was going to rob us and leave, but he didn’t.

Drew shook his head.

He made us walk through the trees away from the truck.

He stayed behind us.

Frank tried to talk to him, tried to ask what he wanted, but the man just jabbed him in the back with the gun.

We walked for maybe 20 minutes.

I tried to remember the direction, tried to keep track, but I couldn’t.

Everything looked the same.

Hayes leaned forward slightly.

Where did he take you? The cabin.

We didn’t see it until we were right on top of it.

He made us go inside.

There was nothing in there except the chairs.

Two chairs in the middle of the room.

He pointed at them.

We sat down.

Drews hands began to tremble.

He chained us, wrists first, then ankles.

He was fast, like he’d practiced.

Then he pulled out the gags.

His mother’s grip on his shoulder tightened, but she said nothing.

He tied them so tight, I thought my jaw was going to break.

Drew continued, his voice barely audible now.

Then he left.

He went upstairs, and we heard him moving around.

After a while, he came back and opened the trap door.

He didn’t come all the way down.

He just stood at the top of the stairs and looked at us.

Then he closed it.

We were in the dark.

Hayes gave him a moment before asking the next question.

How often did he come back? I don’t know.

We couldn’t see.

We couldn’t tell if it was day or night, but I think it was twice a day, maybe.

He’d open the trap door and come down with a flashlight.

He’d take the gag off, but only for a few seconds.

Just long enough to pour something into our mouths.

Some kind of drink.

tasted like chalk.

If we didn’t swallow, he’d pinch our noses shut until we did.

Then he’d put the gag back on and leave.

Did he ever speak to you? No, not once.

3 months, and I never heard his voice.

Hayes interviewed Frank the following day.

His account matched Drews in every significant detail, though his delivery was even more fragmented.

He spoke in short, clipped sentences, his eyes fixed on the wall.

When Hayes asked him what the hardest part of the captivity had been, Frank was silent for nearly a minute.

The silence, he finally said, not being able to talk, not being able to make any sound.

The gag was only off for maybe 10 seconds at a time.

The rest of the time, it was just nothing.

I couldn’t call for help.

I couldn’t talk to Drew.

I couldn’t even cry out loud.

Could you see Drew in the basement? No, it was too dark.

But I could hear the chains when he moved.

Just a little sound, metal on metal.

That’s how I knew he was still there.

That’s how I knew I wasn’t alone.

Frank’s voice cracked.

Sometimes I would move on purpose just to make the chains rattle.

And then I’d wait and Drew would do the same.

It was the only way we could talk.

Hayes asked both boys if they had seen anything that might identify the man.

A tattoo, a scar, a distinctive feature.

Neither had the mask had never come off.

She asked if they’d heard anything from outside the basement, any sounds that might indicate where the cabin was or who else might be nearby.

Drew remembered hearing wind in the trees.

Frank remembered a bird, maybe a raven, calling from somewhere above them.

That was all.

The final question Hayes asked was whether either of them believed the man intended to kill them.

Drew answered first.

I don’t think he wanted us dead, he said slowly.

I think he wanted us exactly the way we were.

Quiet, still under his control.

I think that’s all he wanted.

The FBI’s behavioral analysis unit delivered their full profile to Detective Patricia Hayes on October 2nd, 2000 in a conference room at the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Office.

Special Agent Carla Dennis presented the findings with the clinical detachment of a surgeon describing a tumor.

Beside her sat agent Michael Torres, a criminal psychologist who had spent 15 years studying abduction cases and sexual satists.

The profile they constructed was 23 pages long, but its conclusion could be distilled into a single chilling observation.

The perpetrator had not taken Drew Ryder and Frank Puit to rape them, to ransom them, or to kill them.

He had taken them to possess them.

This offender is what we classify as a power assertive personality.

Dennison began her laptop open to a slideshow of crime scene photographs.

His primary motivation is control, absolute unchallengeable control over another human being.

The abduction itself was a demonstration of competence.

He subdued two healthy young men without a struggle, transported them to a pre-prepared location, and maintained dominance over them for 3 months with minimal risk of detection.

She clicked to an image of the basement, the two empty chairs sitting in the wash of fluorescent light.

The choice of restraints is significant.

Chains are not practical.

Rope would have been lighter, easier to transport, and just as effective, but chains are permanent.

They’re industrial.

They communicate weight, inevitability, inescapability.

The victims described the sound of the chains as the only form of communication they had with each other.

The offender would have known that.

He would have heard it every time he entered the basement.

That sound was part of the design.

Hayes glanced at Sheriff Tom Hackit, who sat at the head of the table with his arms folded.

His expression was unreadable, but his jaw was tight.

Dennis continued, “The gags are even more telling.

” The victims were kept gagged for approximately 23 hours and 40 minutes per day based on their estimates.

The gag was removed only for feeding and even then only partially and briefly.

This wasn’t about preventing them from calling for help.

They were in a soundproofed basement miles from anyone who could hear them.

The gag was about silencing their humanity.

Speech is one of the most fundamental expressions of personhood.

By removing it, the offender reduced them to objects, non- entities, things he could arrange and control.

Agent Torres leaned forward, his hands clasped on the table.

What we’re looking at is someone who derives satisfaction not from physical violence, but from the act of domination itself.

He didn’t beat these boys.

He didn’t sexually assault them.

He didn’t torture them in the conventional sense.

But what he did was in many ways worse.

He erased their agency.

For 3 months they couldn’t move, couldn’t speak, couldn’t make a single decision about their own existence.

They were completely utterly powerless.

And he was the architect of that powerlessness.

Hayes asked the question that had been circling in her mind since the rescue.

Why did he keep them alive? Because dead victims can’t experience subjugation, Taurus said simply.

A corpse has no awareness.

It can’t feel fear or helplessness.

These boys were kept alive because their suffering, psychological, not physical, was the point.

Every time he came down those stairs, every time he forced them to swallow that nutritional drink, every time he retied the gags and walked away, he was reaffirming his control.

They were his to keep, his to manage, his to reduce.

Dennis advanced the slideshow to a map of the region, the cabin marked with a red pin.

Geographically, this offender is local.

The cabin’s location required intimate knowledge of the terrain, the property history, and the patterns of forest service activity.

He would have needed to scout the area extensively, confirm that it was rarely visited, and transport construction materials without being noticed.

That takes time, familiarity, and confidence.

He’s not a transient.

He lives here or nearby.

He knows these mountains the way you know your own home.

She clicked again, bringing up a list of probable characteristics.

Our profile suggests a white male, age 30 to 50, unmarried or divorced, socially isolated.

He likely works in a field that gives him autonomy and involves physical labor, construction, carpentry, forestry, surveying, or equipment operation.

He’s detail oriented, patient, and risk averse.

He plans meticulously and doesn’t deviate from the plan.

The notebook recovered from the cabin supports this.

The entries are sterile, procedural, devoid of emotion.

This is a man who views the crime as a project to be managed, not a passion to be indulged.

Sheriff Hackett spoke for the first time.

You’re saying he’s not impulsive? Not at all.

Dennis confirmed this abduction was premeditated for months, possibly years.

He may have identified Drew and Frank specifically.

Or he may have simply waited for the right victims to appear in the right place.

Either way, he was ready.

The basement was ready.

The chains were ready.

The feeding schedule was ready.

He executed the plan with precision.

Torres added a darker note.

What concerns us most is the absence of an endgame.

Most abductors operate with a specific goal.

Ransom, sexual gratification, revenge.

This offender had none of those.

He kept the victims alive and in the same condition for 3 months, then abandoned the site without explanation.

That suggests external pressure.

Something spooked him or an internal cycle that had completed.

If it’s the latter, the cycle could repeat.

Hayes felt a chill run through her.

“You think he’ll do it again?” “We think he’s capable of it,” Dennis said carefully.

“Men like this don’t stop because they’ve lost interest.

They stop because they’re caught, because they die, or because circumstances prevent them from continuing.

If those circumstances change, if he regains confidence, or identifies new victims, yes, we believe he could do this again.

” The room fell silent.

Hayes looked at the photograph of the basement on the screen, the faded white marks on the concrete floor where the chairs had been positioned with such meticulous care.

Somewhere out there, the man who had measured those marks, who had poured that concrete, who had tied those gags, was living his life.

He was passing people on the street, shopping at the hardware store, maybe even attending church, and no one knew.

Dennis closed her laptop.

The good news, if there is any, is that this level of organization leaves traces.

He had to buy materials, transport them, spend time at the cabin.

Someone may have seen something without realizing it was significant.

We recommend a public appeal for information, focusing on anyone who noticed unusual activity in that area over the past 5 years.

Hayes nodded, though she suspected the appeal would yield nothing but dead ends.

The wilderness had already proven itself an excellent keeper of secrets.

Drew Ryder never went back to Wyoming.

After his release from the hospital in late October, he moved with his parents to his aunt’s house in Boulder, Colorado, a place where the mountains were visible but distant, softened by the sprawl of suburbs and strip malls.

He enrolled in community college in the spring of 2001, but dropped out after a single semester.

Sitting in windowless classrooms triggered panic attacks so severe he once had to be helped outside by campus security.

He found work at a garden center, a job that kept him outdoors and moving.

His mother told Detective Hayes during a follow-up call that Drew couldn’t sleep without a nightlight and refused to close his bedroom door.

He’d stopped fishing.

He’d stopped camping.

The wilderness that had once represented freedom now represented something else entirely.

Frank Puit stayed closer to home.

Though home had become a kind of prison of its own, he moved back in with his parents in Afton and took a job stocking shelves at the grocery store on graveyard shift.

He preferred the empty aisles, the fluorescent hum, the predictable rows of products that never changed.

His father mentioned to a county victim’s advocate that Frank had developed a stutter, something he’d never had before the abduction.

Words would catch in his throat, especially when he was tired or stressed, as if some part of him still remembered what it was like to have speech taken away.

He saw a therapist twice a week for 6 months, then stopped going.

The therapist noted in her final report that Frank displayed symptoms consistent with complex PTSD, but that he was resistant to processing the trauma.

He doesn’t want to talk about it, she wrote.

He wants to forget it ever happened, but forgetting was impossible.

Detective Patricia Hayes kept the case file on her desk long after the active investigation had been scaled back.

The three- ring binder was 2 in thick, filled with witness statements, forensic reports, photographs, and timelines that led nowhere.

She had pinned a single photo to the corkboard beside her desk.

Not the image of Drew and Frank after their rescue, cleaned and bandaged in hospital beds, but the crime scene photo taken in the basement on September 12th.

Two skeletal figures chained to chairs, their faces obscured by white cloth gags, their eyes wide and empty in the flashlight beam.

She kept it there as a reminder.

The case was still open.

The man who had done this was still out there.

The public appeal for information launched in mid-occtober with press coverage across Wyoming and eastern Idaho generated over 200 tips.

Most were well-meaning but useless reports of suspicious individuals who turned out to be seasonal hunters.

Sightings of unfamiliar vehicles that belong to Forest Service contractors.

Vague recollections of someone acting strange at a gas station 6 months prior.

Each tip was logged, cross-referenced, and investigated.

None led anywhere, but three tips stood out.

In November, a retired school teacher named Maryanne Kfax called the tip line to report that in the summer of 1998, she and her husband had been hiking near the Graze River when they encountered a man carrying lumber on a pack frame.

The man had been polite but evasive, offering no explanation for why he was hauling construction materials into the back country.

Maryanne remembered him because he’d been wearing gloves despite the heat and because he’d seemed irritated by their presence, as if they’d interrupted something private.

In December, a surveyor, not Dale Jensen, but a colleague, recalled seeing an old pickup truck parked near a disused logging road in 1997.

The truck had been there on multiple occasions over a span of several months, always in the same spot, always empty.

The surveyor had assumed it belonged to someone maintaining a hunting cabin, but he’d never seen anyone around.

In January of 2001, a clerk at a hardware store in Afton reviewed purchase records at the request of law enforcement and found a series of transactions from 1999 that matched the profile.

Chains, padlocks, bags of concrete mix, rebar, and lumber, all purchased in cash over the course of 4 months.

The clerk vaguely remembered the customer, a quiet man, maybe in his 40s, who drove an older model truck and never made small talk.

The transactions had been unremarkable at the time.

Contractors and ranchers bought the same supplies every week, but in hindsight, the pattern was unsettling.

None of the witnesses could provide a name.

None had thought to write down a license plate number.

The man they described was a ghost present only in fragments and half memories.

A figure who had moved through the community without leaving a mark.

FBI special agent Carla Dennison returned to Lincoln County in March of 2001 to review the stalled investigation.

She met with Hayes in the conference room, the same space where the profile had been delivered 5 months earlier.

Dennis spread the three credible tips across the table and studied them in silence.

He’s local, she said finally.

Or he was.

He knew the area well enough to operate invisibly.

But after the rescue, he would have known the risk was too high to stay.

If he’s smart and everything suggests he is, he’s gone.

Hayes leaned back in her chair.

Where? Somewhere rural.

Somewhere with access to wilderness.

somewhere he can disappear again.

Dennison tapped the photo of the basement.

Men like this don’t stop being what they are.

They adapt.

If he’s still alive, he’s out there.

And if the circumstances are right, he’ll do it again.

The case remained open, but the active investigation effectively ended in the spring of 2001.

Hayes continued to follow up on occasional tips, but the trail had gone cold.

The cabin was dismantled by federal authorities and the basement filled in with concrete, erasing the physical evidence of what had happened there.

The forest reclaimed the clearing.

Within 2 years, there was nothing left to indicate that two boys had been held in chains beneath the earth.

Drew and Frank were invited to speak at a victim’s advocacy conference in 2003.

Drew declined.

Frank attended but left halfway through his scheduled panel.

Overwhelmed by the attention and the questions, a journalist from a true crime podcast reached out in 2012, hoping to revisit the case on its 12th anniversary.

Both young men refused to participate.

Detective Patricia Hayes retired in 2015.

On her last day, she transferred the case file to the county’s cold case archive, but she kept the photograph.

It sits now in a drawer in her home office, a reminder of the invisible man who built a prison in the wilderness and walked away without a trace.

Somewhere in the vast silence of the American West, he may still be out there, waiting in the pines, patient and meticulous, the architect of a horror that left no name and no face.

Only the memory of chains and the terrible unbroken silence of white cloth gags tied too tight to scream.

News

Six Cousins Vanished in a West Texas Canyon in 1996 — 29 Years Later the FBI Found the Evidence

In the summer of 1996, six cousins ventured into the vast canyons of West Texas. They were last seen at…

Sisters Vanished on Family Picnic—11 Years Later, Treasure Hunter Finds Clues Near Ancient Oak

At the height of a gentle North Carolina summer the Morrison family’s annual getaway had unfolded just like the many…

Seven Kids Vanished from Texas Campfire in 2006 — What FBI Found Shocked Everyone

In the summer of 2006, a thunderstorm tore through a rural Texas campground. And when the storm cleared, seven children…

Family Vanished from Stillwater Lake Texas in 1995 — 27 Years Later FBI Found Box with Clothes

In the summer of 1995, the Whitlock family vanished without a trace during their weekend retreat at Stillwater Lake. Their…

Family Vanished from Stillwater Lake Texas in 1995 — 27 Years Later FBI Found Box with Clothes

In the summer of 1995, the Whitlock family vanished without a trace during their weekend retreat at Stillwater Lake. Their…

SOLVED: Arizona Cold Case | Robert Williams, 9 Months Old | Missing Boy Found Alive After 54 Years

54 years ago, a 9-month-old baby boy vanished from a quiet neighborhood in Arizona, disappearing without a trace, leaving his…

End of content

No more pages to load