Hiking couple vanished in New Mexico.

10 years later, their dog was found by a campfire site.

The desert wind swept across the red messes of northern New Mexico, carrying with it the scent of juniper and sage.

It was a landscape that had drawn adventurers, artists, and dreamers for generations.

A place where the earth seemed to breathe in colors.

Burnt orange at dawn, deep crimson at dusk, and an endless cobalt sky stretched overhead.

For Emma Rias and Connor Walsh, this wild corner of the American Southwest wasn’t just a destination.

It was a sanctuary.

Emma and Connor had met 5 years earlier at a climbing gym in Denver.

She was a wildlife biologist with the US Forest Service.

Compact and strong with sun streaked brown hair, usually tied back in a practical braid.

Connor was a freelance photographer whose work appeared in outdoor magazines.

Tall, lean, with a quiet intensity and a camera always slung around his neck.

Their first conversation had been about peragrin falcons.

Their first date had been a sunrise hike in Rocky Mountain National Park.

By their third anniversary, they had summited peaks in three states, camped under meteor showers, and adopted a scruffy Australian cattle dog mix they named Scout.

Scout was more than a pet.

He was their constant companion, bounding ahead on trails, sleeping between their sleeping bags at night, his amber eyes always watching.

Emma joked that Scout had more trail miles than most seasoned hikers.

Connor had photographed him against a 100 backdrops, alpine lakes, desert arches, autumn aspens.

The dog was as much a part of their life as the mountains themselves.

In early October 2015, Emma and Connor drove south from Denver in their well-worn Subaru Outback, heading toward the Ojito Wilderness, a remote and rugged stretch of high desert about an hour northwest of Albuquerque.

It wasn’t a famous park.

No crowds, no paved paths, no visitor centers, just raw ancient terrain carved by wind and time, studded with hoodoo and fossils millions of years old.

Emma had been there once for fieldwork and had promised Connor it was worth the trip.

They planned a 4-day loop hike off trail for much of it with Scout trottting happily beside them.

Before we go further into their story, I want to take a moment to thank you for being here.

If you’re drawn to mysteries that make you think, stories that stay with you long after they end, please consider subscribing to the channel.

Your support means the world, and it helps us bring more stories like this one to light.

Now, let’s continue.

They checked in with Emma’s sister, Laura, the night before they left, sending her a photo of their packed gear spread across their living room floor.

Heading into the Ojito tomorrow, Emma had texted back by Sunday evening.

Signal’s probably going to be non-existent out there, so don’t worry if you don’t hear from us.

Laura had replied with a thumbs up emoji and a reminder to stay hydrated.

It was routine.

Emma and Connor were experienced, responsible, prepared.

On Thursday morning, October 8th, they parked at a dusty trail head near the wilderness boundary.

A park service ranger doing a routine check later that day noted their vehicle in his log.

A blue 2009 Subaru Outback with Colorado plates parked legally.

No signs of distress.

The rangered seeing camping gear visible through the back window, a national park sticker on the bumper, and a dog bowl on the dashboard.

Everything looked normal.

Emma, Connor, and Scout set out under a wide turquoise sky.

The terrain was both beautiful and unforgiving.

Open expanses of sage brush and rabbit brush gave way to sandstone formations that rose like ancient sentinels.

There were no marked trails where they were headed, only washes and ridge lines to follow, the kind of navigation that required a map, a compass, and a respect for the land.

Emma had plotted a route that would take them through a series of canyons, past fossil beds she wanted to document, and up onto a mesa with sweeping views of the surrounding desert.

They carried everything they needed.

A tent, sleeping bags, a water filtration system, dehydrated meals, first aid supplies, and layers of clothing for the desert’s temperature swings.

Connor had his camera equipment carefully packed.

Emma had her field notebook, binoculars, and a GPS unit.

Scout wore a small pack with his own food and collapsible water bowl.

By all accounts, they were ready.

The weather forecast had been clear.

Highs in the mid70s, lows in the 40s.

No precipitation expected.

October was prime hiking season in New Mexico.

The summer heat had broken, but winter snows hadn’t yet arrived.

Conditions were ideal.

Friends later described Emma and Connor as a couple who lived for moments like these.

They weren’t reckless thrillsekers.

They were thoughtful, methodical outdoor enthusiasts who understood risk management.

Emma had wilderness first aid certification.

Connor had grown up camping with his father in Montana.

They had navigated challenging terrain before, from the slot canyons of Utah to the back country of the Wind River Range.

They knew how to read the land, how to conserve resources, how to stay calm when things didn’t go according to plan.

Their apartment in Denver reflected their lifestyle.

Climbing gear hung neatly in the entryway.

Maps covered one wall.

Shelves overflowed with field guides and adventure memoirs.

A photo collage above their couch chronicled their journeys.

Emma laughing on a summit.

Connor silhouetted against a desert sunset.

scout with his tongue out, eyes bright with joy.

It was a life built on exploration, partnership, and a shared reverence for wild places.

On that Thursday morning, as they shouldered their packs and locked their car, they had no reason to believe this trip would be any different.

No reason to think that within days their names would be broadcast across the state, that search helicopters would crisscross the skies above the Ojito, that their families would be gripping each other in a living room, staring at maps they didn’t fully understand, waiting for news that didn’t come.

No reason to imagine that a decade later, long after the searches had ended, long after hope had been buried alongside grief, a campfire in those same red hills would flicker to life again.

And beside it, against all logic and reason, Scout would be found, older, thinner, but unmistakably alive.

But on that bright October morning, all of that was unimaginable.

Emma clipped Scout’s leash to her pack.

Connor adjusted his hat against the climbing sun, and together they walked into the wilderness, their footsteps disappearing into the dust and stone of the high desert.

Sunday evening came and went, without word from Emma and Connor.

Laura Reyes wasn’t immediately concerned.

Cell service in the O’Hito was notoriously patchy.

Really, it was non-existent once you got more than a few miles from the highway.

Emma had warned her about that.

Still, by Monday morning, when her sister’s phone went straight to voicemail for the 10th time, a small knot began forming in Laura’s stomach.

She tried Connor’s number.

Same result.

She told herself they’d probably extended their trip, found a spot they loved, and decided to linger.

Emma had done that before, lost track of time when she was immersed in fieldwork or captivated by a landscape.

Laura sent a text anyway, knowing it wouldn’t deliver until they were back in range.

Hey, just checking in.

Let me know you’re safe when you get this.

By Monday afternoon, the knot had tightened into genuine worry.

Laura called Connors father, Richard Walsh, in Missoula.

He hadn’t heard from them either, but his response was measured calm.

“They’re smart kids,” he said, his voice grally and reassuring.

“Probably just running late.

You know how Emma gets when she’s studying something.

Connor could spend 3 hours photographing one rock formation.

He promised to call if he heard anything, but when Tuesday morning arrived with still no contact, no social media updates, no response to messages, Laura made the call she’d been dreading.

She contacted the Sandaval County Sheriff’s Office and reported Emma and Connor overdue from a backcountry hike in the Ojito Wilderness.

Deputy Miguel Cordova took the report.

He was a veteran officer, a man who’d grown up in nearby Cuba, New Mexico, and knew the high desert the way a sailor knows the sea, with respect bordering on reverence.

He asked Laura the essential questions.

When were they expected back? What was their planned route? What kind of experience did they have? What supplies were they carrying? Laura answered as best she could, pulling up the text messages describing the photo Emma had sent of their gear.

They’re experienced, she kept saying as if repetition could make it more meaningful.

They’ve done this kind of thing dozens of times.

Emma works for the Forest Service.

She knows what she’s doing.

Cordova listened, taking notes in careful handwriting.

When Laura mentioned Scout, the dog, he paused.

A cattle dog mix, you said.

How old? Three years old, blue merl coat, answers to scout.

He goes everywhere with them.

Cordova made a note.

In his experience, dogs were both an asset and a complication in wilderness searches.

They could help their owners navigate, provide warmth, even alert to danger.

But they could also lead people off course chasing wildlife or become injured, creating additional emergencies.

By Tuesday afternoon, a deputy drove out to the Ojito trail head.

The blue Subaru was still there, exactly where the Ranger had logged it on Thursday.

4 days of sun had baked dust onto the windshield.

A parking citation fluttered under the wiper.

Wilderness areas had a 72-hour parking limit.

The deputy peered through the windows.

Camping gear was gone as expected, but a few items remained.

a road atlas folded on the passenger seat, spare sandals, a half empty bag of dog treats.

The doors were locked.

Nothing appeared disturbed.

He called it in.

Within an hour, the Sanderville County Search and Rescue Coordinator, a woman named Terresa Mononttoya, was activating the volunteer team.

Teresa had been running SR operations in northern New Mexico for 15 years.

She’d seen her share of missing hikers, most found within 24 hours, dehydrated and embarrassed.

Some found injured, a few never found at all.

The Ojito wasn’t the most dangerous wilderness in the state, but it was vast, remote, and in October the temperature swings could be brutal.

That evening, as the sun set over the red mazes, painting them in shades of copper and shadow, a command post was established at the trail head.

Volunteers arrived in pickups and SUVs, ranchers, firefighters, offduty EMTs, people who knew the desert and understood what it could do to the unprepared.

Teresa spread a topographic map across the hood of her truck, the paper held down by rocks against the evening wind.

Last seen Thursday morning.

She briefed the assembled team, her voice clear and authoritative.

Two adults, one dog, experienced hikers, well equipped.

We’re now at day five.

We start with their most likely route based on the information from the sister, then expand from there.

We’ve got maybe 90 minutes of daylight left.

I want teams on the primary washes and ridge lines.

Stay in radio contact.

Watch for footprints, gear, anything disturbed.

And listen, if that dog’s out there, he might bark if he hears us.

Laura and Richard arrived that night, driving through darkness to reach the command post.

Laura’s hands shook as she handed Teresa printed photos of Emma, Connor, and Scout.

“Please,” she said, her voice cracking.

“Please find them.” Teresa took the photos, studied them under the harsh light of a camping lantern.

Emma’s bright smile, Connor’s thoughtful gaze, Scouts alert, intelligent eyes.

“We’re doing everything we can,” she promised.

The first night of searching yielded nothing.

Volunteers swept the main approaches, calling Emma’s and Connors names into the darkness.

The words swallowed by wind and distance.

They returned to the trail head, cold, tired, and empty-handed.

Wednesday brought reinforcements.

The New Mexico State Police deployed a search helicopter equipped with thermal imaging.

As it clattered overhead, its rotors beating the thin desert air.

Volunteers on the ground fanned out in organized grids.

They were looking for any sign.

Footprints in the sand, fabric caught on juniper branches, reflections from gear, cans that hikers might have built as markers.

They were also looking for the things nobody wanted to find, but the SAR teams were trained to recognize, signs of injury, distress, or worse.

Connor’s father joined the ground search despite being in his 60s, his face set with grim determination.

He knew these landscapes from his years in Montana.

He knew how quickly things could go wrong.

A twisted ankle could become a death sentence if you were far enough from help.

A wrong turn could lead you miles off course.

Dehydration could cloud your judgment until you made decisions that sealed your fate.

By Wednesday evening, the helicopter crew reported possible sightings.

Color anomalies that might be a tent or clothing in two separate locations.

Ground teams hiked through the night to reach them.

The first was a sunfaded tarp left by previous visitors, half buried in sand.

The second was a patch of orange lykan on a boulder reflecting strangely in the infrared.

Laura sat by the command post fire wrapped in a borrowed jacket staring at her phone as if force of will could make it ring with good news.

Other family members had arrived.

Connor’s younger brother, Emma’s parents, flying in from Arizona.

They huddled together, drinking bitter coffee, asking questions that had no answers.

Where could they be? Why haven’t they activated an emergency beacon? Did something happen quickly, or have they been moving, trying to find their way out? Terresa Mononttoya had seen this before.

The agony of families suspended between hope and grief, clinging to possibilities that grew thinner with each passing hour.

She knew the statistics.

In wilderness disappearances, the first 24 hours were critical.

After 3 days, survival odds dropped sharply.

They were now at day six.

On Thursday morning, a week after Emma and Connor had walked into the wilderness, a volunteer found something.

It was about 8 miles from the trail head near a dry wash bordered by twisted juniper trees.

He radioed it in immediately.

I’ve got a water bottle.

Blue null gene.

Looks relatively new.

Teresa and two other team leaders hiked to the location.

The bottle was lying on its side near a flat rock, the cap missing.

It was indeed relatively new.

No sun damage, no heavy weathering.

It could have been dropped yesterday or a month ago in the desert’s dry air.

Deterioration was slow.

There were no footprints nearby that they could definitively link to Emma or Connor.

The sand was too windswept, too disturbed.

But it was something.

the first real something they’d found.

Teresa marked the location with GPS coordinates and flagged it with bright orange tape.

“This is our new search center,” she announced over the radio.

“All teams, orient from this position.

Expand in concentric circles.” They came through here.

“We just need to figure out which direction they went.” But as the sun climbed higher and the temperature rose into the 80s, the desert kept its secrets.

No more bottles were found, no footprints, no torn fabric, no bark from a loyal dog waiting for rescue.

It was as if Emma, Connor, and Scout had simply dissolved into the red earth, becoming part of the ancient landscape that had witnessed countless other disappearances over millennia.

People who had walked into the vast emptiness and never walked out.

The discovery of the water bottle changed everything and nothing.

It gave searchers a focal point, a piece of evidence that suggested Emma and Connor had made it at least 8 miles into the wilderness.

But it also raised more questions than it answered.

Why was the bottle abandoned? Had they dropped it accidentally or discarded it deliberately to lighten their load? And if they’d passed through this area, when? Which direction had they gone afterward? Terresa Mononttoya ordered a fullscale expansion of the search grid centered on the water bottle location.

By Friday morning, 9 days after the couple had vanished, more than 60 volunteers were combing the Ojito wilderness.

They came from across New Mexico and beyond.

SAR teams from Santa Fe, Albuquerque, even a specialized group from Taos with experience in high desert recovery.

The New Mexico State Police helicopter made multiple passes each day, the distinctive thump of its rotors becoming a constant presence in the vast silence.

The FBI’s regional office sent two agents trained in missing person’s cases.

They interviewed Laura again, going through Emma’s and Connor’s lives with methodical precision.

Were there any signs of relationship problems, financial troubles? Had either of them seemed depressed or mentioned wanting to disappear.

Laura answered each question with growing frustration.

“No,” she kept saying.

“You don’t understand.

They were happy.

They loved their life.

Emma was excited about a promotion at work.

Connor had a gallery show scheduled for November.

They weren’t running away from anything.” The agents also examined the couple’s digital footprint.

emails, bank accounts, social media, everything painted the same picture.

Two people deeply engaged with life, making plans, looking forward.

Their last credit card transaction had been at a gas station in Bernalo on Wednesday evening, October 7th.

Fuel and snacks for the road.

Their last social media posts were from Tuesday.

Connor had shared a photo of sunset over the Sangre de Cristo Mountains with the caption, “Heading south for a few days of desert therapy.” Emma had commented with a heart emoji.

On the ground, volunteers found more traces, a bootprint in hardened mud near an aoyo, preserved from before the couple’s arrival, but potentially matching the tread pattern of the hiking boots Emma’s parents confirmed she owned.

a granola bar wrapper caught in a creassote bush, the same brand visible in the photo Emma had sent Laura of their supplies.

These discoveries fueled brief surges of hope, but they never led anywhere conclusive.

The desert was littered with the debris of previous visitors and definitively linking any item to Emma, and Connor proved maddeningly difficult.

Deputy Cordova led a ground team that pushed deep into a canyon system west of the water bottle location.

The terrain here was technical.

Loose rock, steep drops, places where a fall could be catastrophic.

They moved slowly, carefully, eyes scanning every shadow, every crevice.

Emma, Connor, they called, their voices echoing off sandstone walls.

Scout, here, boy.

But only silence answered.

broken occasionally by the cry of a raven or the rustle of wind through rabbit brush.

Richard Walsh insisted on joining every ground search, despite his age and the punishing conditions.

His face grew more haggarded with each passing day, skin burned by sun and wind, eyes hollow with exhaustion and fear.

Connor’s younger brother, Jake, tried to convince him to rest, but Richard refused.

My son is out there, he said simply, retying his bootlaces for another 12-hour push into the wilderness.

Emma’s mother, Patricia, couldn’t handle the ground searches.

She stayed at a motel in Sanicedro, a tiny town 20 minutes from the trail head where the families had set up a makeshift base.

She spent her days making phone calls to journalists, to Congress people, to anyone who might bring more resources or attention to the search.

Local news stations ran stories.

Emma and Connors photos appeared on broadcasts across New Mexico and Colorado.

Tips began trickling in to the sheriff’s office hotline, but most led nowhere.

Someone thought they’d seen a couple matching their description at a rest stop in Grants.

They hadn’t.

Another caller reported abandoned camping gear near Cho Canyon.

It belonged to a group from Texas who’d already returned home safely.

10 days in, Terresa Mononttoya held a press conference at the trail head.

Television cameras captured her standing before the Red Masons, her face serious and composed.

“We have more than 70 trained personnel conducting coordinated ground and air searches,” she told the assembled reporters.

We are using every resource available.

Dogs, thermal imaging, drones, and experience trackers.

We remain hopeful, but I want to be honest with the families and the public.

This is an extremely challenging environment.

The Ojito Wilderness covers roughly 27 square miles of rugged, remote terrain with numerous canyons, washes, and hidden areas.

We are doing everything humanly possible.

A reporter asked the question everyone was thinking.

What do you believe happened to them? Teresa chose her words carefully.

At this point, we’re investigating multiple scenarios.

They could have become disoriented and traveled farther than intended.

Someone could have been injured, limiting their mobility.

They might be in an area where they can’t see or hear our search efforts.

We’re also considering the possibility of environmental factors, a sudden weather event, wildlife encounter, or other unforeseen circumstance.

Until we have concrete evidence, we’re keeping all options open.

What she didn’t say, couldn’t say publicly, was that with each passing day, the likelihood of finding Emma and Connor alive diminished.

Two experienced hikers with proper gear could potentially survive two weeks in October desert conditions if they found water sources and shelter.

But they were now approaching day 11.

Dehydration, hypothermia from cold nights, injuries that became infected.

Any of these could have already proven fatal.

The dog Scout added another layer to the mystery.

Search dogs brought into track had picked up scent trails, but lost them in areas of heavy rock where scent didn’t cling.

If Scout was still with Emma and Connor, why hadn’t he barked when searchers came near? Dogs could hear approaching humans from remarkable distances.

Unless Scout was injured, trapped, or worse, his silence was difficult to explain.

By the end of the second week, a grim shift occurred in the search.

Teams began focusing on areas where bodies might be concealed, cliff bases where someone might have fallen, deep washes that could hide remains, crevices between boulders.

It was the transition from rescue to recovery.

A change nobody wanted to acknowledge, but everyone understood.

Doctor Marcus Chen, a forensic anthropologist from the University of New Mexico, volunteered his expertise.

He’d worked on wilderness recovery cases before and knew how effectively the desert could conceal human remains.

Scavengers scattered bones, flash floods moved evidence.

The vastness simply swallowed people whole.

He walked the search grids with a different eye, looking for the small things, disturbed earth, circling vultures, the peculiar way vegetation grew differently, where decomposition enriched the soil.

But he found nothing.

Neither did anyone else.

On day 14, a specialized cadaavver dog team from Colorado worked the primary search area for 6 hours.

The dog showed no interest, no alerts.

If Emma and Connor had died in the areas being searched, the dogs should have detected the scent of human decomposition.

The fact that they didn’t meant either the couple wasn’t there or they were so deeply hidden or so far from the search zones that scent hadn’t spread.

The media attention began to fade.

New stories demanded coverage.

Resources were finite.

The state police helicopter was needed elsewhere.

Volunteer SAR teams had jobs and families to return to.

By the 3-week mark, the organized search had shrunk to a core group of a dozen people.

continuing systematic sweeps of the most promising areas.

Laura refused to leave.

She’d taken an indefinite leave from her job as a middle school teacher in Colorado Springs and rented a small apartment in Albuquerque.

Every weekend, she drove to the Ojito with printed maps, water, and a GPS unit, walking alone through the wilderness, calling her sister’s name.

Other family members tried to convince her to accept reality, to begin grieving, but she couldn’t.

Not without proof, she said.

Not without knowing.

Patricia and Emma’s father, David, returned to Arizona, but existed in a state of suspended anguish.

Their daughter’s apartment in Denver remained untouched, rent paid by automatic withdrawal, as if Emma might walk through the door at any moment.

Richard Walsh continued making trips from Montana, hiking the Ojito’s back country with the obsessive thoroughess of a man who couldn’t accept that his son had simply vanished.

Theories proliferated in online forums dedicated to missing person’s cases.

Some were plausible.

Emma and Connor had gotten lost, run out of water, and succumbed to exposure in an area searchers hadn’t yet reached.

Others stretched credibility.

They’d faked their disappearance to start a new life.

But why leave Scout? They’d been abducted by human traffickers in the middle of isolated wilderness.

They’d stumbled upon illegal activity and been killed to protect secrets, possible, but unsubstantiated.

Deputy Cordova investigated every lead, no matter how unlikely.

He checked reports of suspicious vehicles near the trail head around the time of the disappearance.

He interviewed the ranger who’d logged the Subaru, asking if he’d noticed anyone else in the area.

He coordinated with federal authorities to determine if any illegal marijuana grows or meth operations existed in the Ojito that the couple might have accidentally encountered.

Everything came up empty.

The most haunting theory came from an experienced wilderness guide named Tom Beckett, who’d volunteered with the search.

Sometimes, he told Theresa Mononttoya over coffee at the command post, “People just disappear out here.

The desert’s been swallowing folks for thousands of years.

You can fall into a hidden sinkhole.

You can get wedged in a slot canyon that fills with sand.

You can wander into terrain that’s impossible to navigate out of and impossible to search from above.

We like to think we’ve got the wilderness figured out, that with enough technology and effort, we can find anyone.

But the truth is, there are still places that keep their dead.

By mid- November, 6 weeks after Emma and Connor had walked into the Ojito, the official search was suspended.

The families received the news in a conference room at the sheriff’s office.

Teresa Mononttoya delivering it with compassionate professionalism.

We’ve searched more than 75% of the wilderness area, she explained.

Maps spread before them showing the colored zones that had been covered.

We’ve logged over 3,000 volunteer hours.

We’ve used every technological resource available.

If there were obvious signs of Emma, Connor, or Scout in the areas we’ve covered, we would have found them.

I’m so deeply sorry.

Laura stared at the maps, at the vast spaces marked in yellow and orange and red, at the tiny human figures in the search photos dwarfed by endless desert.

“So that’s it,” she asked, her voice brittle.

“You just give up?” “We’re not giving up,” Teresa said gently.

“The case remains open.

If new information comes in, if hikers find something, if evidence emerges, we’ll respond immediately.

and families are always welcome to continue private searches, but we can’t sustain this level of active operation indefinitely.

I wish I had better news.

The families returned to their separate cities, their separate griefs bound together by absence.

In December, a small memorial service was held in Denver, though there were no bodies to bury, no ashes to scatter.

friends shared stories of Emma and Connor, their laughter, their passion for wild places, their love for each other and for Scout.

But without closure, without answers, the grief felt incomplete, a wound that couldn’t heal because it had no defined edges.

The blue Subaru was eventually towed from the Ojito trail head and released to Richard Walsh.

He drove it back to Montana and parked it in his garage, unable to sell it, unable to look at it.

Inside the dog bowl still sat on the dashboard, a half empty bag of treats in the center console, waiting for a dog that would never return.

The Oshito wilderness absorbed the story and moved on.

Seasons changed.

Winter snows dusted the red meases.

Spring brought wild flowers to the washes.

Hikers continued to explore the back country, most never knowing that three souls had disappeared there without a trace.

But the desert remembered it always did.

Years have a way of softening even the sharpest edges of grief.

Not erasing the pain, but making it something you learn to carry.

For the families of Emoryas and Connor Walsh, time moved in a strange, disjointed rhythm, simultaneously crawling and racing, marked not by holidays or birthdays, but by anniversaries of loss, by moments when memory ambushed them without warning.

The first year was the hardest.

Laura couldn’t enter a grocery store without seeing the brand of trail mix Emma loved.

Richard flinched every time he heard a camera shutter.

The sound too much like Connor’s Nikon firing in rapid succession.

Patricia kept Emma’s cell phone charged.

The voicemail greeting preserved like a relic.

Hey, it’s Emma.

Probably chasing lizards or staring at a rock.

Leave a message.

She called it sometimes late at night just to hear her daughter’s voice.

The families maintained a fragile hope that first year.

Every time the phone rang, hearts jumped.

Maybe this was the call, the one that explained everything that brought Emma and Connor home.

When a hiker’s remains were discovered in the Carson National Forest in April 2016, Laura drove 4 hours in a state of nosious dread, only to learn they belonged to a man who’d gone missing in 2012.

Relief and guilt flooded her in equal measure.

Deputy Cordova kept the case file active.

Every few months, he’d pull it out, review the evidence, look at the maps with fresh eyes.

He’d make calls to the state police, to neighboring counties, to medical examiners across the Southwest asking if any unidentified remains matched Emma’s or Connor’s descriptions.

The answers were always no.

In his 23 years of law enforcement, the case haunted him unlike any other.

They were prepared, he told his wife over dinner one night, frustration breaking through his usually calm demeanor.

They did everything right.

Where the hell did they go? Online, the case developed a persistent following.

True crime forums dissected every detail.

Amateur sleuths created elaborate timelines and theories.

A podcast called Vanished: The Ojito Mystery dedicated three episodes to Emma and Connor’s disappearance, interviewing family members, search volunteers, and wilderness experts.

It brought renewed attention.

Tips flooded in for a few weeks, but nothing substantive emerged.

The podcast host concluded with words that would echo for years.

Sometimes the wilderness takes people and it doesn’t give them back.

Sometimes there are no answers.

Manikesh.

By the second anniversary in October 2017, the memorial hikes had become tradition.

Laura organized a group trekk to the Ohio trail head where friends and family gathered to walk a few miles into the desert, leaving flowers and photographs at the spot where the water bottle had been found.

Richard came every year, his face more weathered, his steps slower, but his determination unwavering.

They’d stand in a circle as the desert wind whipped around them.

each person sharing a memory, a story, a moment that kept Emma and Connor alive in their hearts.

Connor’s younger brother, Jake, had taken over managing their social media accounts, which he’d transformed into memorial pages.

He posted their photos regularly, Emma laughing on a summit, Connor focused behind his camera, scout mid leap over a fallen log.

3 years without you, he wrote in October 2018.

still doesn’t feel real.

Still waiting for you to walk through the door and tell us this was all some crazy misunderstanding.

The post received hundreds of comments from strangers offering condolences from other families of missing persons offering understanding that only they could provide.

Life, as it inevitably does, moved forward around the absence.

Laura eventually returned to teaching, though she kept a photo of Emma on her desk and wore a small silver pendant shaped like a compass, a gift Emma had given her years earlier.

Patricia and David moved to a smaller house, unable to maintain the family home filled with Emma’s childhood memories.

Richard retired from his job as a civil engineer, but couldn’t bring himself to clean out Connor’s childhood bedroom, still decorated with his teenage wilderness photography.

The case appeared in missing person’s databases on Namos, the national missing and unidentified person system on the FBI’s missing person’s list.

Emma’s and Connors faces became two among thousands.

Young, smiling, frozen in time, waiting to be found.

Forensic genealogologists working on cold cases occasionally reviewed their file, hoping advances in DNA technology might somehow help.

Though without remains, there was nothing to test.

In 2019, a documentary filmmaker from Santa Fe approached the families about featuring the case in a series on unsolved disappearances in the Southwest.

After much deliberation, they agreed, hoping visibility might shake loose a new lead.

The 20inut segment aired on a regional PBS affiliate in March 2020.

It was well produced, sensitive, thorough, and ultimately changed nothing.

A few tips came in, were investigated, led nowhere.

Then the pandemic arrived, and the world contracted.

The Ojito wilderness closed temporarily.

Search efforts that had dwindled to occasional private excursions stopped entirely.

The families retreated to their homes, grief now compounded by isolation, by the inability to gather and remember together.

Laura held a virtual memorial on the fifth anniversary in October 2020.

Faces of loved ones appearing in video chat windows.

Everyone older, everyone tired, everyone still wondering.

Deputy Cordova retired in 2021.

Before leaving the sheriff’s office, he met with the detective taking over his case load and spent 3 hours reviewing the Emma Reyes and Connor Walsh file.

“I know it’s cold,” he said, tapping the thick folder.

“I know it’s been 6 years, but someone might find something someday.

Don’t let it get buried completely.” The new detective, a woman named Angela Herrera, promised she wouldn’t.

Occasionally, hikers would report finding items in the Ojito that might be related.

A rusted camping stake, a sunbleleached piece of fabric, a broken trekking pole.

Each discovery prompted brief investigations, but none ever definitively connected to Emma and Connor.

The desert was full of abandoned gear, discarded equipment, traces of a thousand previous visitors who’d all made it home safely.

By the seventh and 8th anniversaries, the memorial gatherings had grown smaller.

Some friends had moved away, started families, found it increasingly difficult to hold space for a tragedy that had no resolution.

Richard Walsh’s health began failing, a heart condition exacerbated by years of stress.

His doctor warned him about the annual pilgrimages to New Mexico, but he ignored the advice.

I go until I can’t go anymore, he told Jake simply.

Laura had gone to therapy, processing her complicated grief, the guilt of surviving, the anger at having no closure, the exhausting mental gymnastics of simultaneously mourning and hoping.

Her therapist helped her understand that she could honor Emma’s memory while still living her own life.

That waiting in suspended animation wasn’t what her sister would have wanted.

But knowing something intellectually and feeling it emotionally were different things.

In 2023, as the 8th anniversary approached, Patricia made a decision.

She and David would visit the Ojito one final time.

She announced to the family not to search.

She’d accepted they’d never find answers, but to say goodbye properly, to make peace with the desert that had taken their daughter.

They drove to New Mexico in September, staying in the same motel in Sanicedro, where they’d spent those agonizing weeks in 2015.

They hiked to the water bottle location now unmarked, the orange tape long since blown away by wind.

Patricia carried a small stone she’d brought from their Arizona garden where Emma had played as a child.

She placed it carefully on the ground, anchoring it with larger rocks.

“We love you,” she whispered to the vast emptiness.

“Wherever you are, we love you.” David stood beside her, tears streaming down his weathered face, one hand resting on his wife’s shoulder as the desert wind sang its ancient, indifferent song.

The 9th anniversary in October 2024 was observed quietly.

A few posts on social media, a small gathering in Denver.

The absence was still there, still sharp when poked, but the families had learned to build lives around the hole rather than falling into it constantly.

They joined support groups for families of missing persons, found community with others who understood the unique torture of not knowing.

Laura had even adopted a dog.

Not a cattle dog, she couldn’t bear that, but a gentle golden retriever she named Sage.

Walking her through Denver parks, Laura would sometimes imagine Emma and Scout on trails somewhere, still exploring, still happy in some alternate reality where October 2015 had turned out differently.

As 2025 arrived and spring turned to summer, a full decade approached since Emma, Connor, and Scout had vanished.

A decade of waiting, a decade of wondering, a decade of learning to live with questions that had no answers.

The families had almost resigned themselves to permanent uncertainty, to a mystery that would never be solved, to an ending that would never come.

They had no way of knowing that in the very wilderness that had swallowed three lives in the red canyons and ancient meases of the Ojito, something impossible was about to be discovered.

Something that would shatter their fragile acceptance and replace it with a whole new kind of anguish, a whole new set of unbearable questions.

10 years and the desert was finally ready to give back one of its secrets.

September 2025 arrived with the kind of clear crystalline weather that makes New Mexico’s high desert irresistible to outdoor enthusiasts.

The summer monsoons had passed, leaving the landscape temporarily green, wild flowers blooming in washes that had been bone dry for months.

It was perfect hiking season, and the Oshito wilderness once again drew its modest stream of visitors, photographers chasing golden hour light, geology students studying ancient formations, solitude seekers escaping the noise of civilization.

Among them were Marcus and Jen Okcoy, a married couple from Albuquerque in their early 40s.

Both professors at the University of New Mexico.

Marcus taught geology.

Jen specialized in environmental science.

They’d been exploring New Mexico’s back country for 15 years.

The Ojito was one of their favorite spots precisely because it remained relatively unknown, untouched by the Instagram crowds that had overrun more famous locations.

On Saturday, September 13th, they parked at the familiar trail head and set out for a two-day backpacking loop.

They planned to cover about 12 mi, camping overnight in a canyon system Marcus wanted to photograph for a research paper on erosion patterns.

The weather forecast was ideal.

Highs in the mid70s, clear skies, a waxing moon that would provide natural light for night photography.

They hiked through the morning following a wash that wound between sandstone formations.

By early afternoon, they’d reached their planned camping area, a sheltered spot where the canyon widened, offering flat ground and protection from wind.

But as they approached, Marcus noticed something that made him stop abruptly.

“There’s already someone here,” he said, pointing ahead.

“A campfire site was visible about 50 yards away.

a ring of stones with what looked like recent ash.

And near it, a shape that didn’t belong to the natural landscape.

As they got closer, both of them froze.

It was a dog.

The animal lay beside the cold firing, head resting on its paws, watching them approach with amber eyes that seemed too intelligent, too aware.

It was painfully thin, ribs visible beneath a coat that was matted and sun-faded, but showed the distinctive mottled pattern of a blue merl Australian cattle dog.

The dog didn’t bark, didn’t run, just watched with an expression that Jen would later describe as exhausted recognition, like he’d been waiting for someone to find him.

“Hey there, buddy?” Marcus called softly, crouching down and extending a hand.

“You okay?” The dog lifted its head but didn’t approach.

Marcus noticed immediately that something was profoundly wrong with this picture.

There was no tent, no backpack, no human anywhere in sight.

Just this emaciated dog beside a campfire that appeared to have been used recently.

The stones were arranged deliberately.

There were partially burned sticks in the center and the ash was light gray, not yet fully weathered.

Jen pulled out their emergency supply of jerky and offered it to the dog.

After a moment’s hesitation, the animal stood slowly, stiffly, and walked over.

He took the jerky gently, almost politely, and ate it with careful deliberation.

Jen ran her hands over his coat, checking for injuries.

“He’s old,” she said quietly.

“And he’s been out here a long time.

Look at his pads.

They’re thick as leather.

His teeth are worn.

But Marcus, someone’s been taking care of him.

What do you mean? He’s not starving enough to have been alone for more than a few days.

He’s thin, yes, but not skeletal.

And look, she pointed to a small pile of what appeared to be rabbit bones near the fire ring.

Someone or something has been hunting, providing food.

Marcus examined the campfire more closely.

The stone ring was expertly constructed, the kind of setup an experienced camper would build, but there were no footprints in the sandy soil around it, at least none that were clear enough to identify.

The area had been disturbed by wind, possibly by the dog itself moving around, making it impossible to determine how recently a human had been present.

“We need to check for a collar,” Jen said, gently feeling around the dog’s neck.

Her fingers found it, a worn nylon collar, sunfaded and frayed.

She rotated it carefully until she found the metal tag, tarnished, but still legible.

She read the inscription aloud, her voice catching, “Scout if found.

Contact!” She squinted at the worn engraving.

“There’s a phone number.” Marcus pulled out his satellite phone.

They always carried one in remote areas.

No cell service out here, but we can try this.

He carefully dialed the number engraved on the tag, not knowing it belonged to Emma Reyes, not knowing that number had been disconnected years ago, transferred when Laura had finally closed her sister’s phone account.

The call didn’t connect.

He tried again.

Same result.

We need to get him out of here, Jen said, her professional composure cracking slightly.

Something about this is really wrong, Marcus.

A dog this old, alone in the wilderness beside a recent campfire with no owner in sight.

We need to report this.

They spent the next hour searching the immediate area, calling out for anyone who might be nearby, looking for signs of a camp or an injured hiker.

They found nothing.

No tent, no gear, no footprints that told a coherent story.

It was as if the dog had materialized beside the fire ring spontaneously, which of course was impossible.

Scout, if that’s who he was, followed them dossilely as they packed up to leave.

He moved with a pronounced limp in his rear left leg and seemed to have difficulty with his vision in one eye, clouded with age.

But despite his obvious physical deterioration, there was something almost serene about him, a calmness that didn’t fit the situation.

The hike back to the trail head took twice as long with Scout moving slowly beside them.

Jen kept offering him water from their bottles, which he drank gratefully, but not desperately.

Marcus photographed the campfire site extensively before they left, some instinct, telling him it was important to document everything exactly as they’d found it.

When they reached the trail head, as the sun began its descent toward the Mesa, Jen immediately called the Sandaval County Sheriff’s Office on her cell phone, which finally had service.

She explained the situation to the dispatcher.

They’d found an elderly dog alone in the wilderness beside a recent campfire.

The dog had a tag with a name and disconnected phone number, and they were concerned about a potentially injured or missing hiker.

Deputy Angela Herrera responded to the call personally.

She’d been with the sheriff’s office for four years now, having taken over Cordova’s case load, including a thick file on two missing hikers and a dog from 2015 that she’d reviewed, but never expected to actively investigate.

When she arrived at the trail head 30 minutes later and saw the blue merl cattle dog, something clicked in her memory.

Wait,” she said slowly, staring at Scout.

“What did you say the name on the tag was?” “Scout,” Jen repeated.

Herrera felt a chill run through her despite the warm evening air.

“Stay here,” she said, walking quickly to her patrol vehicle.

She pulled out a tablet, accessed the digital case files, and opened the Emma Reyes and Connor Walsh folder.

Her hands were actually shaking as she scrolled to the photograph section.

There a picture of a young vibrant blue merl Australian cattle dog.

Tongue out, eyes bright.

Caption: Scout, age three, male Australian cattle dog mix, last seen with Emma Reyes and Connor Walsh.

October 2015.

She looked from the photograph to the elderly dog sitting patiently beside the Aoya’s vehicle.

The coloring matched, the build matched, but it was impossible.

Utterly impossible.

I need to make a call, she said, her voice tight.

She contacted the veterinary clinic in Bernalo that serviced the area and explained the situation.

Dr.

Sarah Chen agreed to come immediately.

Within 45 minutes, as dusk settled over the desert, Dr.

Chen was scanning the dog with a microchip reader in the parking area.

Harsh LED lights from the vehicles illuminating the scene.

The reader beeped.

Numbers appeared on the small screen.

Dr.

Chen’s face went pale.

She scanned again to be certain.

Same numbers.

She pulled out her phone and accessed the microchip registry database, entering the ID number with careful precision.

The result appeared.

Scout, Australian cattle dog mix.

Male, date of birth, April 2012.

Owner Emma Reyes.

There was a Colorado address, a phone number, and vaccination records that ended in September 2015.

“This is him,” Dr.

Chen said, her voice barely above a whisper.

“This is the dog that disappeared with Emma Reyes and Connor Walsh 10 years ago.

The words hung in the desert air like something physical, something impossible to fully comprehend.” Herrera immediately contacted her sergeant, who contacted the sheriff, who contacted the state police.

Within 2 hours, the trail head had transformed into a scene reminiscent of October 2015.

Vehicles, personnel, lights cutting through the darkness.

But this time, they had something they’d never had before, a living witness.

Dr.

Chen conducted a thorough examination of Scout in the back of her mobile veterinary van.

He’s approximately 13 years old, she reported to the assembled officers.

Consistent with being three in 2015, he has arthritis, cataracts in his left eye, worn teeth, and he’s underweight, but not critically so.

I’d estimate he’s been without consistent care for, I don’t know, maybe a week or two based on his current condition.

But here’s what doesn’t make sense.

This dog has survived for 10 years in one of the harshest environments imaginable.

Could he have been living wild this whole time? Someone asked.

Dr.

Chen shook her head slowly.

Theoretically possible, but highly improbable.

Australian cattle dogs are intelligent and resourceful.

Yes, some wild dogs do survive in desert environments.

But Scout would have been 3 years old when he vanished.

a domestic dog with no wilderness survival training.

The odds of him learning to hunt, find water, avoid predators, survive temperature extremes, and make it to age 13 alone are, she paused, searching for the right word.

Astronomically low.

So, someone’s been taking care of him, Herrera said.

That would be my professional assessment.

Yes.

Until very recently, the implications crashed over everyone present like a wave.

If someone had been caring for Scout for 10 years in the Ohito wilderness, where were they? Where was Emma? Where was Connor? And why, after a decade, was Scout suddenly alone? Herrera made the call she’d been dreading.

It was nearly 10 p.m.

when Laura Reyes’s phone rang in Colorado Springs.

She’d been grading papers, had almost let it go to voicemail when she saw it was a New Mexico number.

Miss Reyes, this is Deputy Angela Herrera with the Sandaval County Sheriff’s Office.

I’m calling about your sister Emma’s case.

Laura’s world stopped spinning.

In 10 years, she’d imagined this call a thousand times, had rehearsed her reactions to every possible news, but nothing had prepared her for the words that came next.

We’ve found Scout, your sister’s dog.

He’s alive.

The papers slipped from Laura’s hands, scattering across the floor.

What? The word came out strangled, disbelieving.

That’s That’s impossible, ma’am.

He’s been positively identified through his microchip.

We found him today in the Ojito Wilderness.

He’s elderly and in rough condition, but he’s alive.

Herrera paused, letting that sink in before continuing.

We need to ask you some questions and we need to resume search operations immediately because if Scout survived, we need to understand how and we need to find out what happened to Emma and Connor.

Laura sank to the floor, phone pressed to her ear, a sound escaping her throat that was half laugh, half sobb.

After 10 years of silence, the desert had finally spoken.

But what it was trying to say was more terrifying than the silence had ever been.

The discovery of Scout Alive after 10 years detonated like a bomb through the missing person’s community.

Within 24 hours, the story had gone national.

Major news networks dispatched crews to New Mexico.

The families who’d spent a decade in obscurity punctuated by occasional local coverage suddenly found themselves at the center of an international media circus.

“Miracle dog found alive after decade,” read one headline.

“Desert mystery deepens.

Missing couple’s dog discovered at campfire site,” declared another.

But for Laura, Richard, and the other family members who converged on New Mexico within days of the discovery, this wasn’t a miracle.

It was a reopened wound.

Salt poured directly into the exposed tissue of their incomplete grief.

Laura arrived first.

Driving through the night from Colorado, Deputy Herrera met her at the veterary clinic in Bernalo on Sunday morning, September 14th.

Doctor Chen led her to the recovery kennel where Scout was resting on a soft bed, an IV line in his foreg providing hydration and nutrients.

The moment Laura saw him, she broke.

This dog had been part of Emma’s life, had slept in her apartment, had gone on countless adventures with her sister.

She’d seen photos of him as a puppy, as a vibrant young dog.

Now he was ancient, gray around the muzzle, moving stiffly as he lifted his head at her approach.

“Scout,” she whispered, kneeling beside the kennel.

The dog’s tail moved slightly, not the enthusiastic wag of recognition, but something more subdued.

Acknowledgement, perhaps, or simply polite response to a gentle voice.

Laura reached through the kennel gate and Scout sniffed her hand carefully before allowing her to stroke his head.

“Where is she?” Laura asked him, tears streaming down her face.

“Where’s Emma? What happened to her, buddy?” Scout had no answers.

He simply lay there, accepting her touch, his clouded eyes holding a decade of secrets that no one could translate.

The renewed search operation launched immediately.

Terresa Mononttoya came out of retirement to consult Miguel Cordova, despite his retirement and doctor’s warnings about his blood pressure, returned to the Ojito.

Richard Walsh flew in from Montana.

The state police once again deployed helicopters.

S teams from across the southwest volunteered, and this time they had something they’d never had before, a specific location to focus on.

Marcus Okcoy led a team back to the exact spot where he and Jen had found Scout.

The campfire site was photographed extensively, measured, documented like an archaeological dig.

Forensic specialists carefully collected the ash for analysis, bagged the rabbit bones, took soil samples, documented every stone in the fire ring.

The search pattern radiated from this location.

If Scout had been there recently, and if someone had been caring for him, there had to be more evidence nearby.

Ground teams moved in careful grids, eyes scanning for anything that might tell the story of what had happened in this remote canyon over the past 10 years.

On the second day of searching, a team found something about a/4 mile from the campfire site.

It was a small cave, really more of an overhang where the canyon wall had eroded, creating a shallow shelter perhaps 8 ft deep and 12 ft wide.

Inside, protected from the elements, were signs of long-term habitation.

There were remnants of old fires, multiple stone rings indicating the location had been used repeatedly.

There were bones, rabbit, small rodents, what appeared to be snake, suggesting someone had been hunting and eating whatever the desert provided.

Most significantly, there were personal items, weathered but recognizable.

A tattered piece of blue nylon fabric that might have once been part of a tent.

Metal tent stakes corroded by time.

The twisted remains of what had been a water filtration system.

A boot.

A single hiking boot, women’s size seven, the tread worn completely smooth, the leather cracked and sun damage beyond repair, and partially buried in the sandy floor of the overhang, a small metal object that made the lead investigator’s hands shake as he carefully excavated it.

A compass engraved on the back, barely legible beneath corrosion and grime.

To Emma, never lose your way.

Love, Mom and Dad.

Patricia Reyes had given Emma that compass for her 16th birthday.

Emma had carried it on every hike, every camping trip, a talisman more sentimental than practical in the age of GPS.

The fact that it was here in this cave meant one thing beyond any doubt.

Emma had survived the initial disappearance.

She’d made it to this location.

She’d lived here at least for some time.

But where was she now? The cave was processed as a potential crime scene, though there were no obvious signs of violence.

Every item was cataloged, photographed, carefully bagged for analysis.

Forensic anthropologists sifted through the soil looking for human remains.

None were found in, or immediately around the cave.

Cadaavver dogs were brought in to sweep the surrounding area.

They showed no interest.

Dr.

Marcus Chen, the forensic anthropologist who’d volunteered during the original search, returned to examine the site.

He spent hours in the cave studying the fire patterns, the bone deposits, the way the space had been used.

His preliminary assessment was both fascinating and heartbreaking.

Someone lived here for an extended period, he told the assembled investigators and family members at a briefing 3 days after Scout’s discovery.

Based on the depth of ash deposits, the number of distinct fire rings, and the accumulation of debris, I’d estimate habitation spanning months at minimum, possibly years.

The person or persons were surviving on hunted game and whatever water they could find or collect.

its subsistence living, but its survival.

They knew what they were doing.

Both of them? Richard asked, his voice.

Were both my son and Emma here? Dr.

Chen chose his words carefully.

We found one boot definitively linked to Emma through the size and match to the brand her family confirmed she wore.

We found the compass belonging to Emma.

We haven’t yet found items we can definitively link to Connor, but the absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence.

The search is ongoing.

The question that haunted everyone, if Emma and possibly Connor had survived, had managed to establish this shelter, had lived for some indeterminate time with Scout, why hadn’t they been found during the original search? Why hadn’t they tried to signal for help? Terrain analysis provided a partial answer.

The cave was located in a narrow canyon with high walls and a twisted approach that made it nearly invisible from the air.

During the original search, helicopters had flown over this general area, but the overhang would have been impossible to spot unless you knew exactly where to look.

Ground searches had come within half a mile, but hadn’t penetrated this specific canyon system, which appeared on maps as a deadend tributary not worth investigating.

Dr.

Alicia Vance, a psychologist specializing in survival situations, was brought in to consult.

She offered a theory that was difficult for the families to hear, but made tragic sense.

If someone becomes disoriented in wilderness, particularly in complex terrain like this, they can get turned around in ways that seem impossible from outside, she explained.

Emma and Connor might have believed they were traveling toward the trail head when they were actually moving deeper into the wilderness.

Once they realized their error, they may have been too far off course, too depleted of resources to make it back.

The decision to shelter in place, to find a defensible location with water access and wait for rescue, is actually textbook survival protocol.

But we searched for weeks, Laura said, her voice breaking.

We had helicopters.

We had dozens of people calling their names.

How did they not hear us? Sound behaves strangely in canyon systems, Terresa Mononttoya answered gently.

It echoes, gets absorbed by rock, travels in unexpected directions.

They might have heard something and thought it was coming from one direction when the source was actually the opposite way.

Or the searchers might never have gotten close enough to this specific location for sound to carry.

I know that’s hard to accept, but the ojito is more complex than people realize.

The forensic analysis of the items found in the cave proceeded slowly.

The ash from the campfire where Scout was found was tested and dated using radiocarbon analysis.

The results showed multiple burning events, the most recent occurring within the past 2 to 3 weeks.

Someone had built that fire very recently.

The rabbit bones found near the fire showed clear marks of being butchered with a knife.

Clean cuts that indicated human processing, not animal scavenging.

But no knife was found at the scene.

Scout himself was the most bewildering piece of evidence.

Veterinary specialists from the University of New Mexico examined him extensively.

Dr.

Chen’s initial assessment was confirmed.

Scout was approximately 13 years old, consistent with being three in 2015.

But his survival raised questions that had no good answers.

His teeth show wear consistent with a diet heavy in raw meat.

Dr.

Chen reported his paw pads are extremely thick and calloused, indicating years of rough terrain travel.

He has healed fractures in his ribs and his tail that occurred at different times, injuries that mended without veterinary intervention.

His overall muscle structure and bone density suggest a life of continuous physical activity.

This dog has been living in wilderness conditions for an extended period.

But his current weight loss and the specific conditions we found him in beside a recently used fire alone without evident food sources immediately nearby suggest his situation changed very recently.

The implication was inescapable.

Someone had been caring for Scout up until approximately 2 to 3 weeks ago.

Then something had changed.

That person had either left Scout deliberately or had become unable to care for him.

Search teams expanded their radius from the cave and campfire site, now looking not just for decade old evidence, but for recent signs of human presence.

They found more traces.

A faded piece of fabric caught on a juniper branch about a mile from the cave.

Color and material consistent with the clothing Emma had been wearing.

According to photos, a can, a stack of stones that appeared deliberately placed on a high ridge overlooking the canyon, the kind of marker people sometimes build as way points or signals.

On September 20th, 7 days after Scout’s discovery, a team searching a steep area about 2 mi from the cave found something that shifted the entire investigation.

A grave.

It was a shallow depression covered with carefully placed stones located beneath an overhang that offered some protection from the elements.

The rocks had been arranged deliberately, methodically in a way that couldn’t be natural.

Next to it, wedged between two larger boulders to protect it from wind, was a crude cross made from two pieces of juniper wood bound together with what appeared to be strips of fabric.

The forensic team excavated with painstaking care beneath the stones wrapped in the deteriorated remains of what had once been a sleeping bag.

They found skeletal remains, human skeletal remains.

The anthropological analysis was conducted on site initially.

Then the remains were carefully transported to the office of the medical investigator in Albuquerque.

Dr.

Chen led the examination personally.

Two days later, on September 22nd, the families received the news that reconfigured their understanding of everything.

The remains were male, approximately 30 to 35 years old at time of death, height consistent with Connor Walsh’s known measurements.

The skeleton showed evidence of a catastrophic injury, multiple fractures to the left leg, including a compound fracture of the feur that had attempted to heal, but showed signs of severe infection.

There were also fractures to several ribs and the left arm.

Dental records confirmed identity beyond any doubt.

The remains were Connor Walsh.

the estimated time since death based on decomposition patterns and environmental factors approximately 8 to 10 years.

Connor had died around 2015 2017 likely within the first year or two after the disappearance which meant Emma had survived, had buried her partner, had continued living in that cave with Scout for years afterward, alone in the wilderness, griefstricken, somehow surviving against impossible odds.

And if the timeline was correct based on the recent campfire, she might have been alive until just weeks ago.

The question that now consumed everyone, where was Emma Reyes now? The discovery of Connor Walsh’s remains answered one agonizing question while opening dozens more.

Richard Walsh received the news in a conference room at the sheriff’s office, Laura beside him, both of them holding hands across the table as Deputy Herrera delivered the findings with compassionate professionalism.

Richard had spent 10 years not knowing if his son was alive or dead.

Now he knew, but the knowing brought no peace.

He tried to survive, Dr.

Chen explained gently, showing them sanitized photos of the burial site.

The compound fracture he suffered, likely from a fall based on the injury pattern, would have been catastrophic in the wilderness.

Without medical intervention, infection was almost inevitable.

But someone cared for him.

Someone tried to save him.

And when he died, someone buried him with dignity, marked his grave, honored him.

“Emma,” Laura whispered.

“Emma buried him.” The reconstruction of events based on physical evidence and expert analysis painted a heartbreaking picture of survival and loss.

Sometime shortly after Emma, Connor, and Scout entered the Ojito in October 2015, likely within the first 2 or 3 days, Connor had suffered a severe fall.

Perhaps he’d been scrambling across loose rock or navigating a steep section of canyon wall.

The terrain was unforgiving and even experienced hikers made fatal mistakes.

His injuries, the shattered femur, broken ribs, fractured arm, would have rendered him immobile.

Emma, drawing on her wilderness training, and sheer determination, had somehow managed to move or help Connor reach the cave shelter.

She’d attempted to set the bone, to care for him, using whatever resources the desert provided, the presence of certain plant materials found in the cave suggested she tried medicinal remedies.

Willowbark for pain, yrow for infection.

But a compound fracture in primitive conditions with no antibiotics, no sterile equipment, no way to properly immobilize the injury, Connor’s fate had likely been sealed the moment he fell.

Medical examiners estimated he’d survived perhaps 2 to four weeks after the injury.

Then sepsis or complications from infection had claimed him.

Emma had been left alone with his body with Scout miles from help in terrain she no longer knew how to navigate back through.

She’d buried him.

She’d marked the grave.

And then she’d made a choice that still baffled everyone trying to understand.

She’d stayed.

Why didn’t she try to walk out after Connor died? Patricia asked during one of the many briefings, her voice roar with confusion and grief.

She was alone, but she was capable.

She knew wilderness survival.

Why did she stay in that canyon? Dr.

Vance, the survival psychologist, offered possible explanations.

Trauma can profoundly affect decision-making.

Emma had just lost her partner after weeks of trying desperately to save him.

She may have been physically depleted, psychologically shattered, disoriented about which direction would lead to safety.

The cave had become familiar, relatively secure.

Leaving it might have felt more dangerous than staying, and psychologically leaving might have meant abandoning Connor, something she couldn’t bring herself to do.

There was another possibility.

darker and more tragic.

Emma might have tried to leave.

She might have attempted to find help and gotten lost again, returning to the only landmark she knew.

The desert was a maze of identical looking canyons.

Ridges that promised views but revealed only more wilderness.

Without Connor, without her full strength, attempting to navigate out might have resulted in her wandering until exhaustion forced her back to the shelter.

So she’d stayed, and somehow, impossibly, she’d survived.

The evidence suggested Emma had lived in that cave for years.

She’d become proficient at hunting small game.

The bone deposits showed increasing sophistication in her butchering techniques.

Over time, she’d managed water collection, likely using rock depressions that filled during rainstorms and finding seasonal seeps.

She’d kept Scout alive, sharing whatever food she caught.

The dog her only companion in an isolation most people couldn’t fathom.

But then, sometime in late August or early September 2025, approximately 2 to 3 weeks before Scout was found, something had changed.

Emma had left the cave.

She’d built a campfire at a location visible from higher elevations, almost as if she wanted it to be seen, and she’d left Scout there.

The question that haunted the investigation.

Was this intentional? Had Emma finally decided to try to leave the wilderness, leaving Scout behind because he was too old and frail to make the journey? Or had something happened to her, injury, illness, accident that separated her from the dog? An intensive search operation larger than the original effort in 2015 mobilized across the Ojito wilderness.

This time they knew where to focus.

They had a center point, the cave, and a clear timeline.

They were looking for a woman in her late 30s who’d been living in extreme conditions for a decade, who would be profoundly weathered, possibly injured, possibly disoriented.

Thermal imaging helicopters flew grids day and night.

Ground teams with search dogs covered every canyon, every wash, every ridge within a 10-mi radius.

They looked in slot canyons where someone might have fallen.

They checked every overhang and cave system for signs of recent habitation.

They followed game trails that Emma might have used, examined water sources where she might have gone to drink.

Days became weeks.

September turned to October.

The 10th anniversary of the original disappearance arrived.

October 8th, 2025.

Marked now not with a memorial hike, but with active searching, with desperate hope that Emma Reyes might still be alive somewhere in the vast red desert.

Scout remained under Dr.

Chen’s care, slowly gaining weight, his condition stabilizing.

Laura visited him daily, sitting beside his kennel, sometimes talking to him about Emma, sometimes just being present with this living connection to her sister.

Scout had become a celebrity.

His photo appeared in international media.

His story shared millions of times on social media.

But he remained what he’d always been, a loyal dog who’d survived the impossible, carrying secrets that would never be translated into human language.

By late October 2025, despite the exhaustive efforts, Emma had not been found.

No body, no additional evidence of her recent presence beyond the campfire where Scout was discovered.

It was as if the desert had given back what it was willing to share.

Connor’s remains, Scout’s survival, the cave shelter that told a story of incredible endurance, but had decided to keep Emma for itself.

The families faced a new kind of limbo.

They had answers now.

Yes, Connors fate was known.

The mystery of the survival partially solved, but Emma remained missing.

And the possibility that she might still be alive, that she might be injured and unable to signal, that she might be walking through the desert, even now trying to find her way home, made closure impossible.

Laura established a permanent search fund.

Volunteers committed to monthly expeditions into the Ojito, systematically covering areas that hadn’t yet been searched.

Trail cameras were installed throughout the wilderness, monitoring for any human presence.

A substantial reward was offered for information leading to Emma’s location.

Richard Walsh, his health failing but his spirit unbroken, commissioned a memorial for Connor at the grave site, working with the park service to create something permanent and dignified.

But he also insisted on a second marker, a plaque at the trail head that read, “Emma Reyes, still missing.

If you hike in the Ojito, please keep watch.

Please help bring her home.” As winter approached and snow began dusting the high meases of northern New Mexico.

The active search scaled back, but it didn’t stop.

It would never stop until Emma was found, or until the desert finally revealed its last secret.

The questions remain, haunting and unanswerable.

Where is Emma Reyes? Did she leave Scout at that campfire as a signal, a message that she was still alive? Did she attempt to walk out of the wilderness after 10 years of survival, only to become lost again in terrain that had held her captive for a decade? Is she still out there somewhere in the red canyons and endless sky, surviving against odds that defy imagination? Or did the desert, after giving her 10 more years than anyone thought possible, finally claim her as it had claimed Connor? How did she survive for so long? What kind of mental and physical strength does it require to bury your partner, to live alone for years in one of Earth’s harshest environments, to keep yourself and your dog alive with nothing but instinct and will? And perhaps the most painful question for those who love her.

If Emma is still alive, does she want to be found? Has a decade of solitude changed her so fundamentally that the world she left behind no longer feels like home? The Ojito Wilderness keeps its secrets well.

It always has.

The ancient stones and endless sky have witnessed countless stories of survival and loss over millennia.

Emma and Connor’s story is just one more mystery added to the desert’s long memory.

But unlike those ancient forgotten disappearances, this story is still being written.

Scout survived.

Connor’s remains were recovered and laid to rest with honor.

And somewhere in the red dust and sage scented wind, there might still be footprints leading toward an answer.

The desert gave back Scout after 10 years.

Perhaps in time it will give back Emma, too.

Until then, the search continues.

The families wait, and the wilderness holds its silence, beautiful and terrible and eternal.

If this story has moved you, if you find yourself thinking about Emma and wondering where she might be, please leave your thoughts in the comments below.

These unsolved mysteries stay with us because they remind us how vast and unknowable the world still is even in our modern age.

Subscribe to the channel to hear more stories that make you question, reflect, and remember.

Thank you for being here, for bearing witness to Emma and Connor’s story, and for keeping their memory alive.

News

YOUNG BROTHERS VANISHED WHILE HIKING IN MONTANA — 9 YEARS LATER, THEIR BACKPACKS SURFACED IN ICE

Young brothers vanished while hiking in Montana. Nine years later, their backpacks surfaced in ice. In the small town of…

YOUNG AMERICAN COUPLE VANISHED VISITING THE EIFFEL TOWER — 7 YEARS LATER, THEIR CAMERA POSTED AGAIN

Young American couple vanished visiting the Eiffel Tower. Seven years later, their camera posted again. In the bustling suburbs of…

THREE COUSINS VANISHED ON A HUNTING TRIP — 8 YEARS LATER, ONE RETURNED AND CONFESSED A DARK SECRET

Three cousins vanished on a hunting trip. Eight years later, one returned and confessed a dark secret. In the rolling…

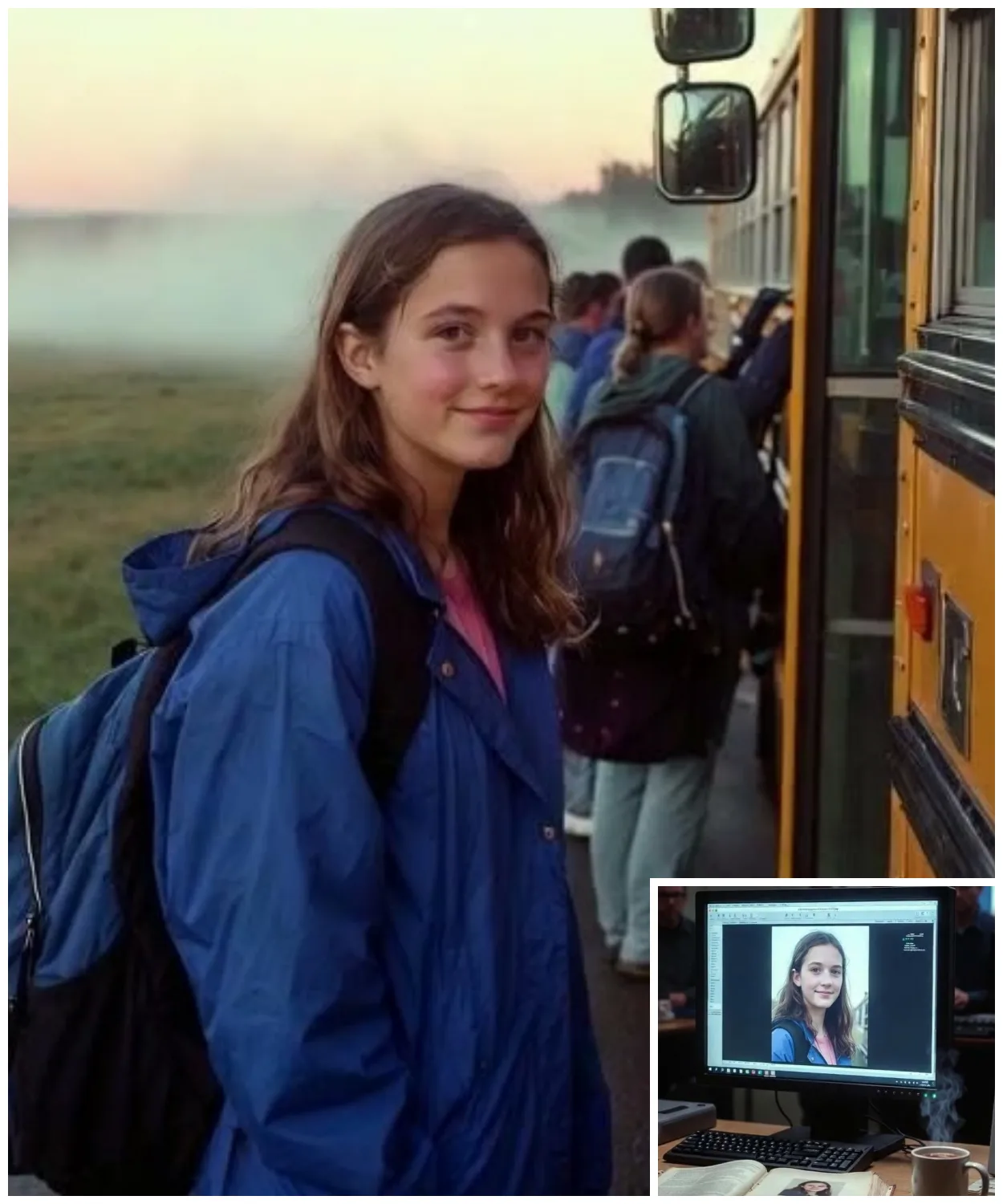

TEENAGE SISTERS VANISHED WHILE HIKING IN GLACIER PARK — 8 YEARS LATER, RANGERS HEARD THEM WHISPERING

Teenage sisters vanished while hiking in Glacia Park. Eight years later, rangers heard them whispering in the wind. The morning…

TWO FRIENDS VANISHED HIKING IN COLORADO.5 YEARS LATER, RANGERS HEARD CRYING FROM INSIDE A CANYON…

Two friends vanished hiking in Colorado. 5 years later, rangers heard crying from inside a canyon. The mountains of Colorado…