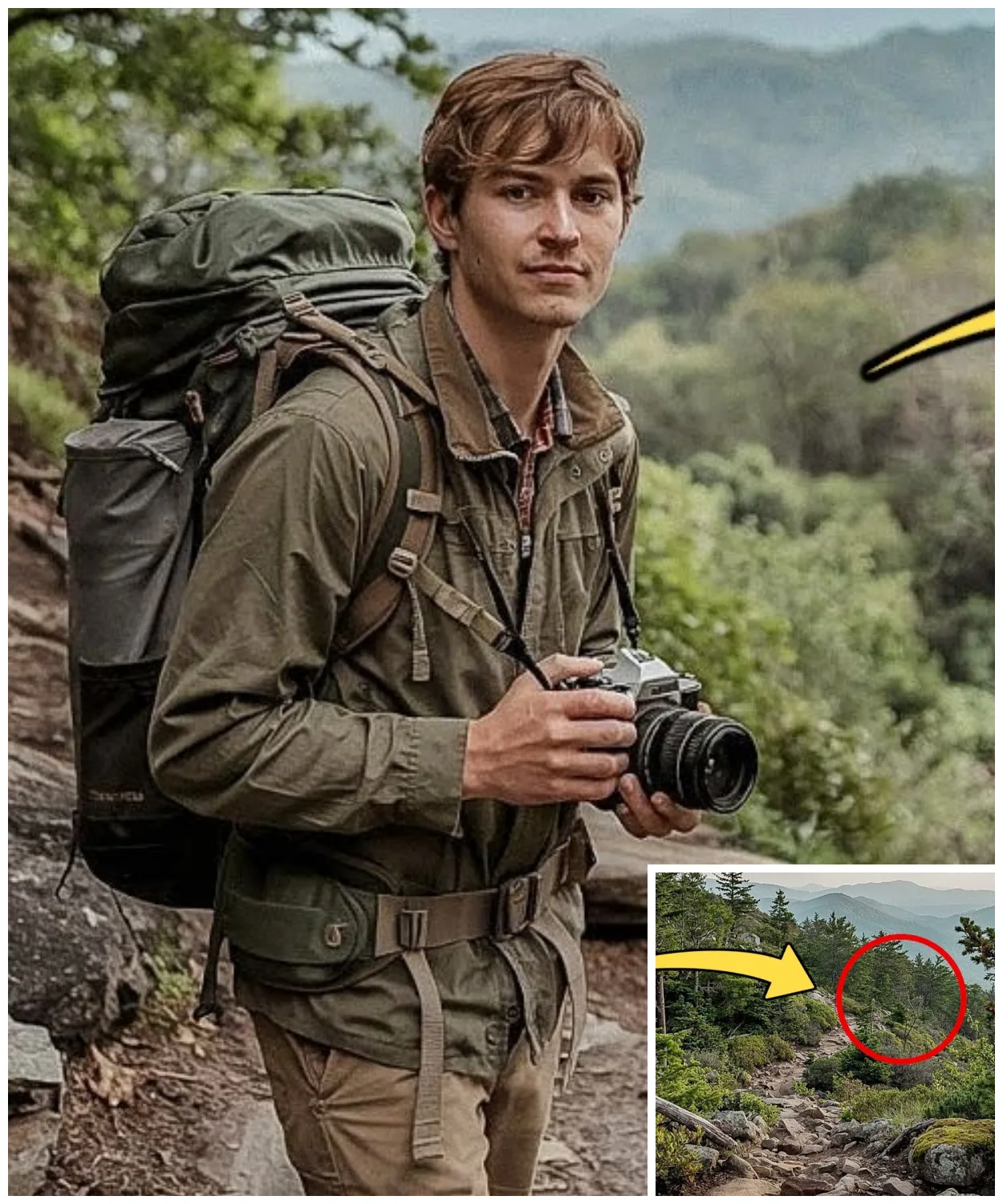

He set out alone, camera in hand, with the quiet confidence of someone who had walked these woods before.

It was supposed to be a three-day solo haikion last escape into the wild before graduation.

But Noah Whitaker never came back.

No distress call, no broken gear, no struggle, just a vanished teenager swallowed by two zero miles of trail that cuts through the spine of the eastern US.

The Appalachin Trail has seen its share of disappearances, but this one was different.

Noah left behind nothing but silence.

For 5 years, his name echoed through ranger stations, family vigils, and missing posters stapled to warn trail signs.

Search teams came and went.

His story was passed among threw hikers around campfires.

Another ghost of the trail.

Another kid the forest didn’t give back until now.

On a fog-drrenched morning near the Tennessee, North Carolina border, a group of campers pitched their tents near a littleknown cutoff trail.

One of them wandered into the woods, chasing a noise he couldn’t quite explain.

What he found would drag Noah Whitaker’s name back into headlines and unearth a truth no one was prepared for.

This isn’t just a story of a teen who vanished.

It’s a mystery that defies logic, one that reveals how easily the forest can take and how rarely it lets go.

The truth behind Noah’s disappearance was hidden in the moss and the shadows.

And for half a decade, it waited.

Now, finally, it’s been found.

But like the best mysteries, the discovery only raised more questions.

Because what they found in those woods wasn’t just bones.

It was a camera, a journal, and a photo Noah never got to share.

A final image that would send a chill down the spine of everyone who saw it.

This is the story of Noah Whitaker, the Appalachian Trail, and the secret that was never supposed to be uncovered.

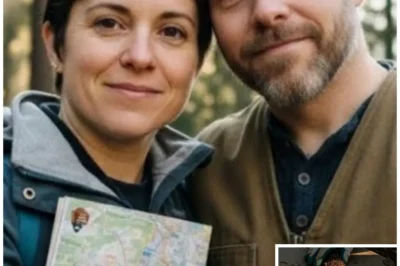

17-year-old Noah Whitaker wasn’t the kind of kid people noticed, at least not right away.

He was quiet in that thoughtful off in the corner way.

The kind of student who stayed behind after class to ask about something not on the test, who always had dirt on his boots and camera straps tangled in his backpack.

He lived in Asheville, North Carolina, a place wrapped in mountains and forest.

It was where he felt most at home beneath the canopy, away from crowds with only bird song and shutter clicks for company.

He wasn’t a thrillseker, not reckless, just curious.

Hiking wasn’t a hobby for him.

It was a second language.

Noah knew the local trails better than most rangers.

He logged hundreds of solo miles, navigating switchbacks and creek crossings while photographing rare salamanders and cloud streaked ridgeel lines.

His dream was to hike the entire Appalachian Trail after graduation from Georgia to Maine.

All to 190 m.

He had the maps, the gear, even a notebook filled with handdrawn sketches of each section.

He called it the long walk.

But before that dream, he planned one final short tripa 3-day solo hike through a stretch he hadn’t yet explored near Blood Mountain.

It was meant to be quiet, intentional, a kind of goodbye to the boy he’d been before, stepping into the world beyond high school.

He left on a Tuesday morning in late March, his pack meticulously organized.

Tent, sleeping bag, trail food, camera, journal, and a compass his grandfather had given him.

He promised to check in by Friday.

The last photo he sent his mom showed a rgeline lit by morning sun, clouds curled below like seafoam.

His caption, “Feels like I’m walking on the edge of the world.

” It was the last anyone ever heard from him.

No one never returned.

His phone stopped pinging.

His GPS tracker showed nothing unusual, then nothing at all.

He had vanished into one of the most heavily trafficked wilderness corridors in the country.

No goodbye, no signal, no sound.

As if the forest had opened up and swallowed him whole.

March 27th, 2023.

The forecast read clear skies with a slight chance of mountain fog, the kind that rolls in like a breath and vanishes just as quickly.

Noah Whitaker stood outside the family home in Asheville, checking the straps on his pack.

Every buckle and zip double-ch checked.

He wasn’t in a rush.

He never was.

Hiking wasn’t a race for Noah.

Hit was a rhythm.

a ritual.

He left just after sunrise, catching a ride with a family friend to the trail head near Neil’s Gap, Georgia, where the Appalachian Trail snakes along the Blue Ridge like an ancient scar.

It was his favorite part of the route as deep switchbacks, dense tree cover, and stretches where the trail opened wide to let the sky pour in.

His mom, Elise, watched him disappear into the trees, her heart tight with that familiar mix of pride and worry.

He’d done this a dozen times before, but this one felt heavier.

He was graduating in two months.

He was planning his first long-d distanceance solo through hike.

This was supposed to be his trial run, a 3-day stretch through Blood Mountain Wilderness, camp two nights home by Friday.

He promised to text every evening when he had a signal.

That afternoon, she received a photo.

Noah was perched on a rocky outcrop above a veil of fog.

Below him, the forest rolled for miles.

Edge of the world.

He’d written beneath it.

His face was lit with quiet joy.

It was the last time anyone saw or heard from him.

When Friday passed with no text, Elise didn’t panic.

It wasn’t unusual to lose service for a day.

But by Saturday morning, with no calls, no messages, and no sign of Noah walking up their driveway with sunburned cheeks and muddy boots, she called the sheriff and everything changed.

Day one was hopeful.

Rangers from Vogle State Park gathered their maps and radios.

They knew the stretch of trail well.

Hikers lost their way out here sometimes.

Most were found within hours, usually on a side trail or camped off the path.

But Noah knew the terrain.

That made this different.

They started near the overlook where he’d sent the last photo.

A search grid was set.

Drones flew overhead, scanning for flashes of color against the dull green forest.

Volunteers came and waves local hikers, school friends, strangers with backpacks and flashlights.

Blood Mountain wasn’t the wildest part of the Appalachin Trail, but it was dense, quiet, and unforgiving in ways people underestimated.

By day three, optimism thinned.

Dogs picked up a trail near Gerard Gap, then lost it near a creek bed.

They found bootprints.

One faint, no drag marks, no signs of a fall.

His tent was still packed.

His trail map folded neatly and stuck between stones like a makeshift marker.

Every day, more people arrived.

Helicopters, scent dogs, high angle rescue teams.

Elise stayed close to the command tent, her fingers wrapped around the phone like it might ring at any second.

But it never did.

By the end of the week, they had covered 30 square miles.

No signal, no clothing, no gear.

It was as if Noah Whitaker had stepped into the trees and vanished.

On the sixth day, just as Hope was beginning to slip into something heavier, a ranger named Denise Pard spotted something off a steep incline near Blood Mountain’s eastern face.

It wasn’t obvious as a flash of fabric where it shouldn’t have been, half concealed by fallen pine needles and a tangle of brush.

She radioed it in, then pushed through the thicket.

What she found chilled her.

A tent half collapsed, pitched at an odd angle near the base of a ridge no marked trail passed through.

It wasn’t where a hiker would camp, not by choice.

Inside, Noah’s gear lay open.

His backpack unzipped, contents scattered like he’d been interrupted.

A small cooler bag still held vacuum-sealed trail snacks and a bottle of electrolyte tablets untouched.

His sleeping bag was still rolled.

No signs of a struggle, no blood, no torn fabric.

Just wrong.

What caught her attention was what wasn’t there.

Noah’s second hiking boot.

One was beside the pack, slightly damp, dusted with leaves.

The other was gone.

Nearby, a mess kit sat unused.

His journal was zipped into the side pocket of the bag.

Pages untouched since March 27th.

The last entry read simply.

Heard movement near camp last night.

Probably deer.

Still didn’t sleep much.

Rangers widened the search grid immediately.

Cadaavver dogs were brought back in.

One circled the site twice, then whimpered and sat.

No clear scent trail.

The location didn’t make sense.

Noah would have never set up camp so far off trail without a reason.

No signs of injury, no steep drop nearby, no storm damage.

And the boot, why would he have left a boot behind? A camera was missing from his gear list.

His mom said it was a Canon DSLR, always around his neck.

It wasn’t there.

Neither was his compass.

They bagged the gear and flagged the site, but nothing else turned up.

Just a tent in the woods, eerily untouched, as if Noah had simply stepped outside and never come back.

When a hiker goes missing, there are patterns.

Search and rescue manuals call them lost person behaviors.

They chart what most people do when panic sets in.

Walking in circles, heading downhill, seeking water, trying to return to the last known point.

But Noah Whitaker didn’t follow those rules.

The location of his campsite half a mile off any marked trail told them something different.

It wasn’t the place someone disoriented would stumble into.

It was deliberate chosen.

But why there? Experts say hikers leave trails for three reasons.

First, injury.

You fall, get disoriented, try to find help, end up further off course.

But there were no drag marks, no blood, and no gear left in panic.

Second, confusion.

You think you’re on a shortcut.

You lose the path in the dark.

But Noah had a GPS watch, multiple topo maps, and trail experience beyond his years.

Disorientation didn’t fit.

That left the third reason, the one no one wants to say out loud.

Sometimes hikers leave the trail to follow something or someone.

Whether it’s the flash of a person through the trees, a strange noise in the distance, or even a call for help that seems real until it isn’t, people veer off for reasons they believe are logical in the moment.

Some speculate about what Noah heard that night.

His last journal entry hinted at it.

Movement too close for comfort.

If it had been an animal, he would have written more.

He always did.

If it had been a person lost, injured, calling for help, Noah would have checked.

He was that kind of kid.

But then there’s the other explanation.

The one that sits like a shadow at the edge of every search.

That he didn’t just follow someone.

That someone was watching.

That the missing boot wasn’t forgotten.

it was left behind.

In the days that followed, theories bloomed like mushrooms in the dark.

But the evidence said this wasn’t a typical lost hiker case.

Not a misstep, not a mistake.

Noah Whitaker hadn’t wandered off blindly.

He was missing, but not lost.

10 days into the search, just when efforts were beginning to shift toward recovery rather than rescue, a volunteer spotted something half submerged in a creek bed below Slaughter Gap.

It was barely recognizable.

A fragment of lined paper soaked through its edges torn and clinging to the rocks like something that didn’t want to be found.

They lifted it gently, slid it into a plastic sleeve, and brought it back to base camp.

What they read wasn’t much, just one line scrolled in black ink, the handwriting confirmed by his mother as Noah’s.

I think I saw something last night.

No date, no context, just those seven words.

The search team gathered around it in silence.

A ranger muttered that it could mean anything.

A bear, a shadow, a dream.

But it wasn’t the words that chilled them.

It was where the note was found.

The creek ran a good mile south of the offtrail campsite.

If the page had been torn from his journal, how had it ended up there? It wasn’t carried downstream.

The current was too weak, and the note had been weighted under small stones, as if someone had placed it there deliberately.

Noah’s journal, recovered at his tent, was missing several pages at the back.

Until then, no one had thought much of it.

Now, the gaps seemed more intentional.

Searchers returned to the area with renewed urgency.

They checked nearby hollows, underbrush, and root formations.

Nothing.

But the presence of that note changed the tone of everything.

No longer was the narrative about a hiker lost to the elements.

It was about someone who saw something, something he couldn’t explain, something he didn’t understand.

and perhaps something that was watching him back.

Blood Mountain has always had a reputation.

Long before it was a way point for hikers, it was something else as sacred to some, avoided by others.

The Cherokee called it a place of unrest.

Legends spoke of battles, spirits, things best left undisturbed.

Most of that folklore faded into the background, buried under gear reviews and trail maps.

But locals never quite forgot.

After Noah vanished, old stories started creeping back into conversation.

A maintenance worker at Neil’s Gap swore he saw lights flickering through the trees just before dawn, weeks before the boy went missing.

Not flashlights, not campfires.

Pale cold blue, the kind that doesn’t throw shadows.

An Appalachian Trail blogger once wrote about the hump, a low vibrating sound that came from nowhere and followed her for miles near Jared Gap.

She said it made her teeth ache.

She never hiked that section again.

A retired forest ranger who lived in Suchez came forward quietly telling reporters off the record that there were areas in the mountains shadow where compasses spin and radios die.

He warned rookies not to linger there after dark.

But the most unsettling accounts came from other hikers.

Not about lights, not about sounds, but about whispers.

Faint rhythmic murmurss drifting through the trees.

Never loud enough to understand.

Always just enough to unsettle.

One hiker claimed the whispers repeated his name.

Another said they weren’t whispers at all, but breathing.

All of these stories had been circulating for years, dismissed as stress, sleep deprivation, or the tricks of wind through branches.

Until Noah, until a boy with experience, preparation, and good judgment vanished in a place that doesn’t forget.

What if the stories were more than stories? What if Noah didn’t imagine something watching him? What if he was right? Elise Whitaker stood on the edge of the ranger station’s gravel lot.

Reporters clustered around her like flies to grief.

She wasn’t crying.

She hadn’t cried in days.

Her voice, when she spoke, was steady, not rehearsed, not performative, just raw, measured, tired.

My son knew those trails, she said, her eyes fixed on the treeine behind the cameras.

He wasn’t reckless.

He wasn’t lost.

Something happened to him out there.

The press conference was supposed to be a routine update, a gesture to the public, but Elise turned it into something Moria a plea, a challenge, a declaration.

She talked about Noah’s planning, how he’d mapped the trip weeks in advance.

She described his gear, how he always packed extra batteries, water tablets, a first aid kit, even when hiking locally.

She mentioned his instinct for direction, how as a child he could follow deer paths and return without needing to backtrack.

Noah wasn’t confused.

He wasn’t careless.

He didn’t just wander off and forget how to come home.

The crowd was quiet.

Even the reporters lowered their cameras.

Her voice cracked only once when she described the photo he’d sent.

The last image.

Edge of the world.

I think he saw something, she said, more to herself than the cameras.

I think someone was out there with him.

When asked if she believed he was still alive, Elise hesitated just for a moment.

Then she said, “I believe my son fought to come back.

I believe whatever happened, he didn’t just give up.

After the press cleared, she returned to the command tent, sat beside a stack of maps and volunteer sign-in sheets, and resumed what she did every day, waiting for news.

Any news? But no new signs would come.

Only silence.

By day 28, the search had lost its momentum.

The volunteer turnout had thinned.

Helicopter hours were limited.

Dog teams were rotated out and not replaced.

The maps on the incident board, once cluttered with pins and markers, now sat mostly still.

There were no new leads, no new sightings.

The last possible clue had been a discarded water bottle near Kowok Mountain, but it didn’t match the brand Noah packed.

The forest had given nothing back.

Officially, the case remained open.

Unofficially, it was slipping into that quiet category no one wanted to name cold.

The rangers stopped saying, “When we find him,” they started saying, “If.

” Elise noticed the shift in language, the way people stopped meeting her eyes, how conversations grew shorter, more polite, more distant.

She stayed longer at the trail head each day, watching hikers come and go, hoping one might say they’d seen something, anything.

Noah’s posters remained stapled to trail signs and bulletin boards, edges curling in the sun.

A QR code linked to a missing person’s site that saw fewer clicks by the week.

The sheriff’s office issued one last statement thanking the community for their efforts and encouraging anyone with information to come forward, but everyone knew what it meant.

Noah Whitaker had joined a growing list, the ones who vanished without a trace, who stepped into the trees and were never seen again.

In the end, there was no ceremony, no official closing of the case, just a slow fading of urgency, a silence that settled like mist over the trail, thick and unmoving.

The forest had taken him and it wasn’t giving him back.

When the search ended and the noise quieted, speculation took its place.

The forums came first, Reddit threads, Facebook groups, survivalist blogs, then the podcasts, then the headlines that didn’t ask what happened.

But what if? What if Noah hadn’t gone missing by accident? Some pointed to his journal entry.

I think I saw something last night.

They read it not as fear of a shadow or a sound, but of a person, a figure just out of frame.

Some believed Noah had been followed.

Others suggested he had been lured.

His Instagram was public.

He posted trail updates, location tags, photos of overlooks with timestamps.

To most, it was a digital scrapbook, but to others, it was a map, a way to track him.

One online commenter claimed to have seen a strange exchange in Noah’s comment section two weeks before the trip.

someone telling him to check out Blood Mountain for the real view.

The comment had since been deleted.

The theory spread.

Noah had made contact with someone online, someone who offered a tip, a trail, a meetup, someone who knew he would be alone.

Elise denied it fiercely.

He didn’t run off.

She told reporters he didn’t plan anything.

He packed for 3 days.

He bought two freeze-dried meals.

His return bus ticket was still on the fridge.

But the theories wouldn’t stop.

Some wondered if he’d fallen into the trap of those niche online form soft grid communities, anti-tech wanderers, groups that glorified vanishing.

The most persistent theory, that he never planned to come back, that Noah met someone in the woods who offered something else.

But none of it added up.

If he’d left willingly, why leave behind everything? His gear, his journal, one boot, why not take the camera? Why not say goodbye? And if he met someone with bad intentions, where was the evidence? No sign of a struggle, no defensive wounds, no dropped item pointing to a second person, just absence.

Still, when logic ends, imagination begins.

And when a story has no ending, people write their own.

It started as a whispering old trail tale passed between hikers at shelters and fire pits.

A man who lived off-rid deep in the woods near Slaughter Creek.

No phone, no tent, just a tarp, a pack, and stories no one could prove.

He never spoke, some said.

Others claimed he offered foraged berries in exchange for news.

They called him the grey man.

As the week stretched into months, Noah’s name started appearing in the same breath.

What if he hadn’t disappeared? What if he’d joined someone out there? A ranger recalled a hiker mentioning a kid with a camera at Cow Rock shelter weeks after the search had ended.

He said the boy was quiet, thinner than he should have been, eyes tired.

But when pressed for more details, the hiker couldn’t remember the date, couldn’t even be sure if the memory was real.

Elise clung to the idea at first.

Maybe he’d had a break.

Maybe something had snapped and he just walked away from his old life.

He was a teenager, quiet, internal, the kind of boy who felt things deeply.

But even that theory had holes.

Noah was goal oriented.

He planned things to the hour.

His long-term dream of hiking the entire Appalachin Trail didn’t include disappearing into the woods forever.

And if he’d gone off-rid, where was the trail? No transactions, no sightings, no footprints leading deeper into the mountains, just dead ends.

Still, the hermit theory grew legs.

A blog surfaced with a blurry photo taken near Whitley Gapwatt appeared to be a young man crouched beside a small fire.

Too grainy to confirm, too suggestive to ignore.

theories morphed.

Maybe Noah had been taken in by someone.

Maybe he was injured and rescued by a backwoods recluse.

Maybe he had found solace in silence, trading civilization for solitude.

Elise stopped reading the forums.

Every new theory was a wound reopened.

But for some, the hermit theory made sense.

It was cleaner than foul play, kinder than death.

A teenager overwhelmed by the world simply choosing to vanish into the trees.

But even that idea comes with a question no one could shake.

If Noah was still out there, why hadn’t he come back? The first post appeared 7 months after Noah disappeared.

It was buried in a wilderness survival thread on Reddit written by a user called Apphiker43.

The username didn’t raise eyebrows at first.

Trail names are common in online communities, and most go unnoticed, but what caught people’s attention was the post’s title.

I saw the kid from the news.

He’s not lost.

He just won’t leave.

It wasn’t long before the theories lit up again.

The message was short, written in choppy sentences.

He’s alive.

He doesn’t want to be found.

Said the woods are quieter.

Said they watch at night.

Left him food.

Never saw him again.

Users immediately connected it to Noah.

The post referenced a boy with a camera and one boot.

Details never made public.

Moderators removed it within the hour, citing unverified claims.

But the internet never forgets.

Screenshots were taken.

Comments poured in.

Theories exploded.

Some believed it was Noah himself reaching out in code.

Others thought it was a hoax.

Some sick troll feeding off a family’s grief.

But then came more posts spread across different subs.

Survival missing persons.

Even Appalachin folklore forums.

Each message was cryptic.

Vague references to the boy who sleeps near the broken creek and someone else out there.

The poster refused to respond to DMs.

They never commented, only posted and disappeared.

One message read, “Sometimes I hear him.

He hums when it gets too loud.” Another said simply, “He’s not alone.” A few amateur sleuths traced the IP address to a public library system in Georgia, but nothing more.

The username stopped posting after its fifth message.

The account was deleted.

For weeks, the online community buzzed.

People combed through the original search maps, cross-referenced creek names, trail mile markers, even weather data.

Elise was warned not to engage, but someone sent her the screenshots anyway.

She read them all twice.

Her voice was flat when she told reporters, “If someone’s out there and knows something, even if it’s a lie, I need to hear it.” But the silence returned, and Apphiker 43 never came back.

3 days after Noah disappeared, a cell tower in Robin County, Georgia, picked up a signal, a short-lived ping, untraceable, just long enough to register a device, then gone.

It was flagged later during a routine audit by the cell provider’s technical team.

The phone’s IMEI number was cross-cheed.

It matched Noah’s device, 60 mi from his last known location.

The tower’s reach was limited, designed for local traffic, mostly hikers and small town residents.

There was no reason Noah’s phone should have connected there unless it had moved.

Unless someone had moved it.

Investigators were cautious.

Phones glitch.

Ghost pings happen.

A device left powered on in just the right position can sometimes catch a stray signal.

But this wasn’t random.

It was active for 48 seconds, just long enough to receive an update.

Long enough to check in.

Theories flew.

Maybe someone found the phone and powered it on.

Maybe Noah had moved south injured, confused, or worse.

The search expanded briefly toward Robin County.

Rangers canvased trail heads, shelters, even nearby diners.

No sightings, no additional pings.

The phone went dark again, this time for good.

Some experts speculated that if the battery had enough juice, it could have turned itself on during a hard restart.

Others weren’t so sure.

The location didn’t match any known path Noah would have taken.

It was offc course over rugged terrain through sections of trail rarely maintained.

The idea that here someone else had made it there in 3 days seemed improbable, but not impossible.

A few internet detectives connected the timing to apphiker 43 claiming the ping occurred just hours before their first post.

A coincidence? Maybe.

Or maybe not.

Elise held on to the report like a tether.

He had it in his pocket, she told friends.

Maybe he tried to call.

Maybe he was trying to come back.

But no call records existed.

No texts were sent.

Just a whisper of signal in the dark.

And then nothing.

It wasn’t part of the official record.

No written report.

No radio transcript.

Just a quiet conversation on a cold afternoon with someone who had once worn the uniform.

His name was Mark Denlin, retired ranger, 27 years with the US Forest Service.

He reached out to Elise privately after reading about Noah’s case in a regional magazine.

They met at a diner just outside Dalenega.

He kept his voice low, his eyes flicking to the windows every time a car passed.

“There are places,” he said, stirring his coffee.

“Places we used to log, but didn’t linger in.

We call them dead zones.

You lose GPS, radios cut out, and people when they’re out there, they change.” Elise asked what he meant.

Mark just shook his head.

“It’s not the woods that scare me.

It’s what they do to people, what they pull out of them.” He said there were sections of trail his team avoided after dark.

Not because of wildlife, not because of terrain, but because something felt wrong, tangibly wrong.

I’ve seen grown men step off a marked trail and come back white as ghosts, mumbling about whispers, shapes in the trees, always the same spots.

Blood Mountain was on that list.

He remembered a case from years ago.

a hiker who turned up 2 days after going missing.

Shoes gone, scratches across his arms.

Wouldn’t say a word about what happened.

Just packed his gear and left the state.

We never put it in the reports, Mark said.

Can’t list strange vibes as a reason to close a section, but we knew.

Elise pressed him.

Had he ever heard of anyone surviving in those zones? Had anyone ever come back after 5 years? Mark didn’t answer right away.

He just looked at her.

The kind of look that carries the weight of every name that never made it off the mountain.

If he’s out there, he said finally, he’s not out there alone.

June 12th, 2028.

A group of three campers made their way down an unmarked ravine just south of Cow Rock Mountain.

It wasn’t part of the route they planned.

One of them, Logan Ree had lost his knife somewhere upstream.

They doubled back, took a wrong turn, and followed the sound of running water, hoping to refill their bottles.

What they found wasn’t water.

At the bottom of the ravine, half buried beneath a lattice of fallen trees and tangled brush, sat something unnatural, a shape too square, too symmetrical.

Logan thought it was a crate at first, or an old trail marker.

Then he got closer.

It was a backpack, mold covered, faded, torn at one shoulder strap.

Inside, a rusted compass, a cracked lens cap, and a laminated photo ID tucked into a side pocket.

Noah Whitaker.

They froze.

One of them started filming.

The footage would be everywhere by the end of the week.

A few feet away, propped upright against a tree as if someone had placed it there intentionally, was a spiralbound journal swollen with moisture.

The cover peeled off as Logan opened it.

Most of the pages were blank or water damaged beyond recognition.

But near the back, still legible, was one sentence written in jagged black ink.

They come at night.

I stopped counting the days.

Authorities closed off the ravine within hours.

Rangers, forensic teams, and investigators flooded the area.

Helicopters hovered low.

Tape went up fast.

What they uncovered over the next 48 hours would reframe the entire case.

Noah Whitaker had been there.

Not for hours, not for days, for years.

The discovery of the backpack should have been the end.

It should have been closure.

But it wasn’t.

The day after Noah’s belongings were recovered, investigators expanded the search, fanning out from the ravine and working uphill through thick brush and splintered undergrowth.

Just beyond a narrow game trail, one ranger spotted something strange and old popppler tree split at the base, hollowed by age and weather.

Inside, tucked carefully into the dark cavity as though placed there by someone who didn’t want it found easily, was a leatherbound journal, worn, water stained, but unmistakably his.

Noah Whitaker was etched faintly into the inside cover, the ink faded, but intact.

Beneath it, a line from a thorough quote written in his handwriting, “Not till we are lost do we begin to understand ourselves.” It wasn’t the kind of notebook you took on a weekend hike.

This one was thicker, heavier.

A book for someone planning to be gone a long time.

Pages near the front were normal, observational, birds, weather, trail conditions, mentions of places he’d camped, sketches of moss patterns, and handdrawn maps.

But as the pages turned, the tone began to shift.

There were gaps, long stretches without dates.

And then something else, a change.

He wrote less about the world around him and more about what he felt, about what he heard and what he saw.

One entry, I think the forest is trying to keep me.

The path changes when I look away.

Another heard someone whisper last night, “Too close, no fire, just breathing.” Then toward the final section, the writing became frantic, scratched across the page in uneven lines.

Ink smudged as if written in the dark.

Investigators photographed every word, every page.

But it was the last three entries that haunted them most.

The handwriting had changed.

Still Noah’s, but different, tighter, more jagged, as though each word took effort to get onto the page.

I sleep in pieces now.

Something circles the camp.

I don’t hear it walk.

I hear it waiting.

The next page had only two lines.

The moon isn’t right anymore.

It follows too slowly.

The shadows don’t match the trees.

And then the final entry scrolled diagonally across the last usable page, nearly cutting into the leather binding.

They know I’m awake.

I try not to dream, but I do.

In the dream, I’m underground, but I’m not dead.

I can still hear the wind.

I think they’re trying to bury me alive.

The page was smeared with dirt and something else.

A faint reddish brown stain near the corner.

Forensics would later determine it was blood.

What disturbed investigators most wasn’t just the content, but the clarity.

These weren’t the ramblings of someone lost to madness.

They were precise, intentional.

There were no entries after that.

No signature, no farewell, just silence.

Who they were, no one could say.

No one never described them, never drew them.

Just the pronoun again and again they.

But the fear in those last words was clear.

Noah hadn’t simply disappeared.

He had been hunted, watched, and by the end, he knew it.

It was a junior field investigator who found them.

Less than 40 yards from the tree where Noah’s journal had been hidden, just beyond a narrow split in the ravine wall, he spotted a pile of stones that didn’t belong.

At first glance, it looked like debris.

Just another cluster of rockfall, half covered in moss and years of decay.

But something about the arrangement was too deliberate, too.

Even a shallow can no more than 2 ft high.

When they pulled the rocks away, the smell hit first.

Not fresh, not rot, just the stale, earthy scent of time old death held in the dark too long.

Beneath the stones were bones long stripped by weather and scavengers.

A partial skeleton curled as if bracing against the cold.

The torso collapsed inward, ribs fractured, clavicles snapped.

Beside the remains lay a single hiking boot, laces still looped.

Same make model as the one found near Noah’s abandoned tent 5 years earlier.

Same size.

The bones were clothed, or what was left of them.

Tattered remnants of a weatherworn shirt, shredded nylon lining from a jacket.

In the shirt pocket, they found a rusted camera battered but intact.

A Canon DSLR exactly like the one Noah was known to carry.

The lens was shattered.

The memory card was still inside.

Everything stopped.

They secured the site and began cataloging evidence.

Nearby trees were marked, soil samples taken.

No sign of wildlife disturbance, no evidence of a second body, no tools, no rope, no weapon, just noahore what was left of him.

Tucked into a quiet, forgotten crease of forest.

The positioning of the body was strange.

There were no drag marks, no indication of trauma to the skull.

It looked like he’d been placed there, not hastily, not dumped, intentionally, as if someone or something had buried him with care.

For a moment, the ravine went still.

No wind, no birds, just the quiet sound of boots shifting on soft ground.

The team backed away slowly because finding Noah Whitaker’s body didn’t end the mystery.

It only deepened it.

The remains were flown out the next morning.

The forensic lab in Atlanta moved fast, aware of the weight the case carried.

Within 48 hours, the dental records confirmed what everyone already knew, but hadn’t said out loud.

It was Noah.

Elise was notified in person.

She didn’t speak for a full minute after hearing the words.

Then she whispered, “I always knew he didn’t just leave.” But the confirmation wasn’t the end.

The real clue piece no one expected was still waiting.

Sealed inside an evidence bag marked camera recovered.

Technicians dried the DSLR, disassembled the body, removed the corroded battery.

Miraculously, the memory card was undamaged.

163 files, mostly photos of trees, ridge lines, streams, the kind of detail Noah was known for until the last five.

The first showed a dark blursome thing partially obscured by tree limbs, hard to make out.

The second was clearer, a humanoid shape, tall, thin, just off center, unmoving, no face, just a long, dark outline blending into the shadows.

The third was closer, much closer.

The subject was behind a tree, maybe 10 ft from Noah.

It hadn’t moved, or it had.

The blur was too sharp to be wind, too still to be natural.

The fourth photo was taken from ground level, crooked, like he dropped the camera and fired blind.

And the fifth, the final image, was black, but not empty.

When enhanced, faint light streaks appeared along the edges.

At the center, two eyes reflective, wide apart, watching.

Technicians reviewed the timestamps.

The photos were taken hours after sunset, nearly a full day after his last journal entry.

He was still alive, still running, still being watched.

The official report would mark Noah Whitaker’s death as undetermined exposure related complications.

a careful way of saying they didn’t know what killed him, but those last five images told another story, one no one could explain.

The photos were never released to the public.

Elise was given copies.

She never showed them to anyone.

All she said was, “He didn’t die afraid.

He fought, but those who saw the pictures said otherwise because something had followed him and in the end caught him.” The memory card was nearly full.

Image after image showed what everyone expected.

Landscapes, plant close-ups, shadow play on mossy trunks.

Noah’s photographers’s eye was steady, his framing deliberate.

Each shot told a story of someone who knew how to see.

But then came the last photo.

File name? I am gone 162.

It didn’t match the rest.

It was chaotic, tilted, blurry, motion blurred in a way that suggested panic, not movement.

It captured Noah mid-frame.

face turned toward the lens, wideeyed, mouth open like he was shouting.

His hand was outstretched, pointing past the camera into the trees behind him.

His expression was unmistakable.

Terror.

This wasn’t a selfie.

The angle was too low, too offc center.

It looked like the camera had been dropped or hastily triggered during a fall.

Noah wasn’t looking at the lynch, was looking past it, at something behind it.

Investigators passed the photo between themselves in silence.

One of them, a technician from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, quietly set it aside, labeling it as possibly critical.

The woods behind Noah were shrouded in late twilight shadows bleeding into one another, branches twisted like reaching arms.

At first glance, there was nothing there, just the forest.

But something in the photo unsettled everyone who looked at it.

It wasn’t just Noah’s fear.

It was the sense that something else had been in the frame, just out of sight.

That night, the photo was sent to forensic imaging analysts in Quanico.

High resolution scans, light curve mapping, shadow enhancement, not to doctor the image, but to reveal what the camera might have seen before Noah’s hand shook or slipped or froze.

They enhanced it carefully, layer by layer, and when they saw what was hidden there, everyone went quiet.

The enhancements took two days.

Software cleaned the grain, pulled brightness from the shadows, adjusted contrast, and isolated movement artifacts.

And there it was, a shape.

On the far right of the frame, half concealed by a thick tree trunk, stood a dark humanoid silhouette.

Not blurred, not ghosted, not a trick of the trees.

It was there, still upright, watching.

The figure was unusually tall, too tall, 7 ft at least.

Its limbs were thin and wrong, disproportionate.

Its head tilted slightly, as if caught mid-motion.

There were no facial details, no eyes, but the line of the shoulders, the tension in the format was undeniably aware.

It wasn’t wearing clothes, not in any conventional sense.

There was no visible skin either, just a uniform charcoal darkness, as if it absorbed the light around it.

The bark behind it faded into shadow, but the figure didn’t blend.

It stood apart as if it wasn’t part of the forest at all, as if it didn’t belong there.

One analyst described the posture as curious.

Another used the word predatory.

They ran checks against regional wildlife, costumed hoaxes, even visual anomalies caused by lens damage.

Nothing matched.

Nothing came close.

The timestamp placed the photo less than 20 minutes before the presumed time of death.

In that moment, Noah had seen something, had pointed at it, tried to capture it, maybe to warn, maybe just to prove he wasn’t imagining it.

He hadn’t been.

The official report made no mention of the figure.

It was marked as inconclusive shape consistent with environmental distortion, but the raw photo unredacted, unfiltered version told a different story.

Noah wasn’t hallucinating.

He was documenting.

And what he caught on camera wasn’t natural.

It was real, and it had been standing right behind him.

Long before Noah Whitaker ever stepped onto that trail, the place he died already had a name.

Locals called it the devil’s thumb.

It wasn’t marked on official maps, but hikers knew it.

A jagged, crooked outcropping that jutted from the ridgeeline like a snapped bone.

The trail never touched it.

There was no reason to.

It wasn’t scenic.

It wasn’t safe.

The trees there grew too close together.

The wind didn’t move the same way.

Compass needles spun slightly, not wildly, just enough to second guessess.

GPS signals blinked in and out.

Wildlife avoided it.

Those who wandered near described the same feeling pressure, like the air thickened, like the forest was holding its breath.

Some said it felt like walking into a memory that wasn’t yours.

Others just called it wrong.

Noah had made camp only a mile from the base of the ridge.

His journal mentioned the landscape changing, path shifting, footsteps he couldn’t place.

What he experienced may not have started there, but it ended there.

Rangers confirmed that the ravine where his remains were found sat in a narrow valley directly beneath the thumb.

The light barely reached the floor even at noon.

It was shaded in a way that felt permanent.

A few older locals refused to hike within a mile of it.

One retired fire warden remembered helping retrieve a body there decades ago.

Lost hunter found curled in the same fetal position buried under stacked rocks.

His rifle was never recovered.

No one built there.

No one camped there.

And yet somehow Noah ended up there by choice or by force.

There was no trail to follow in, none to follow out, only silence.

And the name carved into local memory long before this story ever began.

The Devil’s Thumb.

Just east of the thumb, past a wall of thick laurel and half collapsed forest, lies pine hollow, a stretch of wood so densely grown, it feels like a place that doesn’t want to be entered.

GPS maps label it as national forest.

Locals call it something else.

Cursed.

The stories stretch back over a century.

Before the area was a hiker’s haven, it was settler country, isolated homesteads, handbuilt cabins, small families who came west looking for land and ended up swallowed by the wilderness.

One such group was the Varner colony, a name pulled from scattered ledgers and church registries dating back to the 1,840s.

They moved into Pine Hollow in 1,847 and then vanished.

No census data, no graves, just rumors.

Locals spoke of a cult that had formed among the settlers, one that worshiped something older than scripture.

Not God, not the devil, something else, something in the woods.

Hikers have reported seeing strange carvings etched into trees along the hollows edge.

Circular symbols, triangles enclosed in rings, always low to the ground, as if made by hands that move close to the earth.

A survey team in 1,992 found remnants of an old foundation deep in the hollow.

No structure, just stones in a square.

In the center, a circle of blackened earth that hadn’t grown vegetation in years.

The report said possible fire pit.

The locals said burning ground.

Some claimed to have heard chanting from inside the forest late at night.

Others spoke of people who hiked in and never hiked out.

Whispers became legends.

Legends became warnings.

No one built trails through Pine Hollow, not because they couldn’t, but because they didn’t want to.

And when Noah’s final journal entries were compared to those old reports, the symbols, the circles, the shadowed figures in the trees, the similarities were hard to ignore.

Noah Whitaker didn’t just disappear into the woods.

He wandered into a story the forest had been telling long before he was born, and he never came back out.

2 days after Noah’s remains were flown out of the ravine, a second team returned to sweep the surrounding area for anything missed.

They weren’t expecting much standard procedure, but what they found changed everything.

Just 50 yards up slope from the rock car etched into the bark of a birch tree was a symbol.

Faint, weatherworn, but unmistakable.

A circle intersected by three lines forming a jagged triangle at its center.

Not random, not animal scratches.

intentional.

And it wasn’t alone.

Over the next few hours, they found more.

Six in total, spread across a tight perimeter surrounding the site.

Some were recent, freshly carved, sap still beating at the edges.

Others had darkened with age, nearly swallowed by new bark, but they were all the same design.

When photographed and cataloged, the markings rang a bell for one of the researchers, a folklore archavist consulting remotely.

She dug up a scan page from an obscure 19th century hermit’s journal written by a man named Silus Reed.

He had lived alone near Pine Hollow in the late 1,800s kept pages of cryptic notes and obsessive sketches.

In one margin, crudely drawn, was the same symbol.

Reed called it the ward, a marking used to keep watchers away and mark the edge of the quiet land.

He described hearing voices at night, shapes that moved without sound.

He believed something lived in the hollow, something that didn’t want to be seen.

Silas disappeared in 1,891.

His journal was all that remained.

Now, over a century later, the same symbol had reappeared, circling the spot where Noah Whitaker had died.

It wasn’t a coincidence.

Someone or something had marked that land, and Noah had walked straight into it.

The first national story hit within 24 hours of the forensic confirmation.

Missing teen found after 5 years with journal of forest haunting.

From there it spread like wildfire.

Cable news podcasts Reddit threads stacked a 100 comments deep.

Everyone had a theory.

Everyone had a headline.

Noah’s final photo, the one with him pointing terrified was leaked by an anonymous source.

Within hours it was everywhere.

Blurred, cropped, zoomed, memed, debated.

And then came the symbol.

A grainy snapshot of one of the tree carvings made its way online.

The shape, the lines, the ancient simplicity of it.

Conspiracy forums exploded.

Some called it a hoax, claiming the whole story was a well-crafted viral campaign.

Others swore it was proof of something older, something buried, something that finally had a name.

The divide was instant and sharp.

Skeptics argued about light artifacts and mental illness.

Believers dissected every journal entry, every photo, treating Noah’s words like scripture.

Elise refused interviews at first, but the pressure mounted.

Cameras staked outside her house.

Microphones pushed through car windows.

When she finally spoke, she said only this.

My son didn’t find a ghost story.

He found something real and it killed him.

The public ate it up.

Paranormal specials aired within days.

Travel vloggers flocked to the area hoping to catch something on film.

A true crime docue series started development within weeks.

But locals didn’t join the spectacle.

They stayed away.

Some cut down trees bearing the symbols.

Others hung crosses from their porches because for them this wasn’t content.

It was a warning.

And they knew the forest wasn’t done yet.

Elise Whitaker made the journey in late July, nearly a month after the discovery.

The forest was still.

Summer’s heat pressed through the canopy and the trail head was empty.

She didn’t bring a camera crew.

No reporters, just a ranger escort and her son’s ashes.

The hike in took hours.

When they reached the base of the ridge, Elise paused, looking up at the looming rock formation locals called the devil’s thumb.

No words, just a breath.

The team led her down into the ravine where the earth had been disturbed, then carefully restored.

The tree where Noah’s journal had been found still stood, silent and weathered.

Someone had tied a piece of cloth to one of the branches, a quiet token left by another visitor.

Elise stepped forward and placed a letter in the hollow, folded neatly, sealed with tape.

She didn’t read it aloud, but she later told a friend what it said.

I finally brought you home.

She scattered a small portion of Noah’s ashes at the base of the tree, letting the wind carry the rest into the hollow beyond.

The ranger said at least stood there for several minutes, unmoving, listening.

Not for voices, not for shadows.

just for silence.

And then she turned and walked back up the trail.

There were no cameras to record the moment.

No headlines that night.

Just a mother saying goodbye to her son where the forest had once swallowed him whole now.

For the first time, it gave something back.

3 weeks later, a solo hiker named Jenna Cruz uploaded a video to a backpacking forum.

She’d been section hiking along the Blue Ridge Loop about 10 mi south of the ravine where Noah was found.

The clip was short, just over a minute, but it spread quickly.

In it, Jenna pans across a stand of trees near her campsite.

“Something felt weird last night,” she says, her voice low, like the woods went quiet too fast.

Then the camera jerks slightly, focusing on a tree trunk just to the right of her tarp setup.

“There it is, freshly carved, deep, and clean.

The same symbol, the circle, the three intersecting lines, identical to the ones found near Noah’s final camp.” Anyone know what this is? She asks, laughing nervously.

Creepy, right? The comment section erupted.

Don’t camp there again.

Not a coincidence.

Check your tent tonight.

But one comment stood out.

Posted by a new user with no profile picture, no history, just a name.

Watcher 3.

The message read, “It’s moving again.” Jenna didn’t respond.

The thread was locked by moderators the next day after a flood of troll posts and heated arguments.

But those who had followed Noah’s story from the beginning recognized what it meant.

The woods hadn’t forgotten, and the shadow, whatever it was, hadn’t stayed buried.

It had simply moved on.

Noah’s discovery did more than bring a tragic story to light it unearthed patterns no one had noticed before.

Not officially, but quietly, in rooms where investigators talk in low tones and sift through yellowed files, it started a whisper, a pattern.

Five other cases spanning two decades were pulled from the shelves.

Each had been labeled missing hiker, presumed lost, or environmental exposure.

All unsolved.

All vanished without a trace.

All within a 50-mi radius of Pine Hollow.

Each case shared chilling common threads.

Young, experienced hikers, solo or small groups, disappearances near sections of trail that ran parallel to dense, unprolled forest.

Most had sent a final message, texts, photos, voicemails, moments of beauty captured before silence fell.

In one case, a 24year-old woman named Haley Brooks disappeared in 2011 near Cow Rock knob.

She’d been an avid backpacker.

Her last known location was 3 mi from Noah’s final site.

Her journal was later found wedged between rocks, pages torn.

One line was underlined, “They don’t like light.” Another case, Michael Trent, age 20, vanished in 2006 near a spring west of Pine Hollow.

His last cell ping placed him off trail.

A search dog picked up a scent that vanished at the edge of a ridge line.

Now investigators circled back.

The symbols reignited the files, the journal entries, the strange sightings.

Some saw the connections as folklore wrapped in coincidence.

Others weren’t so quick to dismiss it, especially after drone footage from a recent sweep showed one more symbol carved fresh just a hundred yards from where Michael Trent disappeared nearly 20 years ago.

Too fresh to ignore.

Officially, the cases are under review.

Unofficially, a pattern is forming and something or someone is still out there.

The fog rolls in low, clinging to the earth like breath.

A lone hiker makes his way up a narrow stretch of the Appalachian Trail.

Boots crunching over damp leaves.

His pack sways gently.

There’s no music playing, no company, just the steady rhythm of a solo hike in the quiet hush of mistcovered trees.

He pauses near a bend where two pine trees frame the path like silent centuries.

Pulls out a bottle of water, checks the map on his phone, and then something catches his eye.

a tree, older, wide trunk, just off the trail.

He steps closer, frowns.

There, near the base, etched faintly into the bark, is a symbol, a circle.

Three intersecting lines, fresh.

The bark is still curled from the blade.

Sap hasn’t yet dried.

He stares at it, puzzled, tilts his head, takes a photo, thinking maybe he’ll post it later.

Another strange marking on another strange hike.

He doesn’t notice the silence.

Not yet.

The bird stopped minutes ago.

The wind no longer moves through the branches.

Somewhere behind him in the fog, a shadow shifts.

The camera lingers on the symbol as the hiker disappears into the trees.

No music, no narration, just mist.

And the faint sound may be imagined of something breathing slow and steady, watching, waiting, still there.

This story was brutal.

But this story on the right hand side is even more insane.

News

Couple Vanished In New Mexico Desert – 5 Years Later Found In ABANDONED SHELTER, Faces COVERED…

In August 2017, a group of hunters searching for wild donkeys in the New Mexico desert stumbled upon an old…

Woman Hiker Vanished in Appalachian Trail – 2 Years Later Found in BAG SEALED WITH ROPE…

In August of 2013, 34year-old Edith Palmer set out on a solo hike along a remote section of the Appalachian…

15 Children Vanished on a Field Trip in 1986 — 39 Years Later the School Bus Is Found Buried

In the quiet town of Hollow Bend, the disappearance of 15 children and their bus driver during a 1986 field…

Climber Found Crucified on Cliff Face — 4 Years After Vanishing in Yosemite

When a pair of climbers discover a preserved figure anchored to a narrow shelf high on Yoseite’s copper ridge, authorities…

Couple With Dwarfism Vanished in Yosemite — 4 Years Later an Old Suitcase Is Found WITH THIS…

Norah Sanders and Felix Hartman walked into Yoseite like they had every spring. But that year, something trailed them from…

22-Year-Old Hiker Vanished on a Trail in Utah — 3 Years Later, Her Boots Were Found Still Warm

22-year-old hiker vanished on a trail in Utah. 3 years later, her boots were found still warm. In the crisp…

End of content

No more pages to load