In 2015, a hunter stumbled upon a bear cave in the mountains of Colorado and saw something that changed everything he knew about an incident that had happened 18 years earlier.

A human skull lay among rocks and animal bones.

But it had too many holes for it to be an accidental death.

22 bullet wounds, all from a small caliber rifle.

It was not an accident or a bear attack.

It was a hunt.

The story began in the summer of 1997.

Dan Morris lived in the small town of Durango in southwestern Colorado.

He was 29 years old, worked as a mechanic at a local auto repair shop, and spent almost every weekend in the mountains.

Dan was not a professional climber or extreme sports enthusiast.

He simply loved nature and silence.

He went alone, without company, without unnecessary noise.

His roots always lay across the San Juan Range, an area he knew well enough to feel confident but wild enough to remain interesting.

At the end of June that year, Dan took a week’s vacation.

He told his boss at the car service center that he was going to the mountains, that the route was standard, nothing complicated.

He planned to walk along several trails in the Cole Creek Pass area, pitch his tent somewhere by a stream, go fishing, and spend some time alone.

A week seemed like enough time for such a route.

Dan packed his backpack on the evening of June 26th.

He took a tent, a sleeping bag, food for 8 days with a small reserve, a water filter, a map, and a compass.

He left his phone at home.

There was no cell service in the mountains anyway, and he saw no point in carrying extra weight.

His neighbor saw him loading his things into his old 1989 Ford pickup truck.

She remembered that Dan looked calm and in a good mood, waved to her, and said he would be back in a week.

On the morning of June 27th, Dan left Durango for the mountains.

He was last seen at a gas station on the outskirts of town.

He filled up his tank, bought a bottle of water, and some chocolate bars.

The cashier remembered him because he was a regular customer, always polite and quiet.

He paid in cash and drove north on Highway 160.

That was the last trace of him.

Dan planned to leave his car in the parking lot near the trail head at Cole Creek Pass.

It was a popular spot among hikers and fishermen, and there were always cars there, so leaving a pickup truck for a week was quite normal.

But when he didn’t return home a week later on July 4th, his boss called the local sheriff’s office.

Dan was never late and always kept his word.

If he said a week, he would be back in a week.

A day later at most, if he was delayed on the way back.

A search party went out on July 5th.

They found Dan’s pickup truck exactly where it should have been.

The car was parked near Cole Creek Pass, locked with no visible damage.

Nothing unusual inside.

A map on the passenger seat, an empty coffee cup in the cup holder, several music cassettes.

The keys were not in the car or nearby.

Dan had taken them with him.

It made sense.

He always carried his keys in his backpack pocket in case someone tried to break into the car.

The searchers began combing the trails from the parking lot.

They knew Dan had planned to head toward the creek.

It was a standard route for solo hikes in the area.

The trail led through a pine forest, then climbed a small ridge and descended to the creek where there were good places to camp.

The distance was about 8 km one way, no more than 3 hours on foot, at a leisurely pace.

The weather at the end of June was good with no rain or sudden temperature changes.

At night, it cooled down to plus 5° and during the day it warmed up to plus 20, ideal conditions for hiking.

The search party included local rangers and volunteers.

Among them was Thomas Grave, a ranger who had been working in the area for several years.

He was 36 years old and lived in a small house on the outskirts of Silverton about 40 km from Durango.

Thomas knew the mountains better than anyone else in the area.

He had participated in almost every search operation in the area and knew every trail, every stream, and every cave.

His help was invaluable, and he was always the first to volunteer for searches.

The group covered the entire route to the creek, checked all possible camping spots, searched the banks, and looked into several caves and crevices where a person could take shelter in case of bad weather.

Nothing.

No traces of a tent, a fire, footprints, nothing to indicate that Dan had actually reached the creek.

They expanded the search area, combed the surrounding trails, and checked alternative routes.

Maybe Dan had decided to change his plan and gone in a different direction.

Maybe he had gotten lost and strayed from the path.

The mountains were vast, and even an experienced hiker could get lost if he strayed from the trail.

The search continued for 2 weeks.

Every day, groups went into the mountains, checked new areas, called his name, and listened.

They used dogs to pick up his scent from the car, but the dogs couldn’t find the direction.

Either Dan wasn’t following the main trail, or his scent was too old and mixed with hundreds of other smells.

By mid July, it was clear that the chances of finding Dan alive, were slim to none.

Two weeks in the mountains without food or water, even if he was injured or lost, was too long.

The search was called off, but the case was not closed.

Dan Morris was officially listed as missing.

His family did not give up hope.

Dan’s mother, Carol Morris, continued to visit Durango every few months, putting up posters with his photo, talking to locals, and asking anyone who went into the mountains to be vigilant.

She believed that sooner or later, someone would find something that would answer the question of what had happened to her son.

But the years passed and nothing changed.

Dan seemed to have vanished into thin air in the mountains.

In 1998, a tourist reported seeing a tent off the main trail, but when a search party checked the spot, there was nothing there.

In 2001, an old backpack was found, but it did not belong to Dan.

In 2005, someone claimed to have seen a man resembling Dan in a neighboring state, but it turned out to be a mistake.

Each time the family hoped and each time their hopes were dashed by reality.

Gradually interest in the case faded.

The case of Dan Morris became one of many unsolved disappearances in the Colorado mountains where people vanish without a trace every year.

Thomas Grave continued to work as a ranger.

He was an exemplary employee, disciplined, reliable, always ready to help.

His colleagues respected him for his knowledge of the area and for never shying away from difficult tasks.

Thomas lived alone without a family, his life revolving around work and the mountains.

On weekends, he often went into the woods for the whole day, saying that it helped him relax and escape the routine.

No one thought there was anything strange about that.

Many rangers and locals preferred solitude and nature to the hustle and bustle of the city.

18 years passed.

The Dan Morris case remained in the archives and the family resigned themselves to never getting any answers.

Carol Morris died in 2012 without ever knowing what had happened to her son.

It seemed that the story was over and no one remembered the missing mechanic from Durango.

But in the fall of 2015, everything changed.

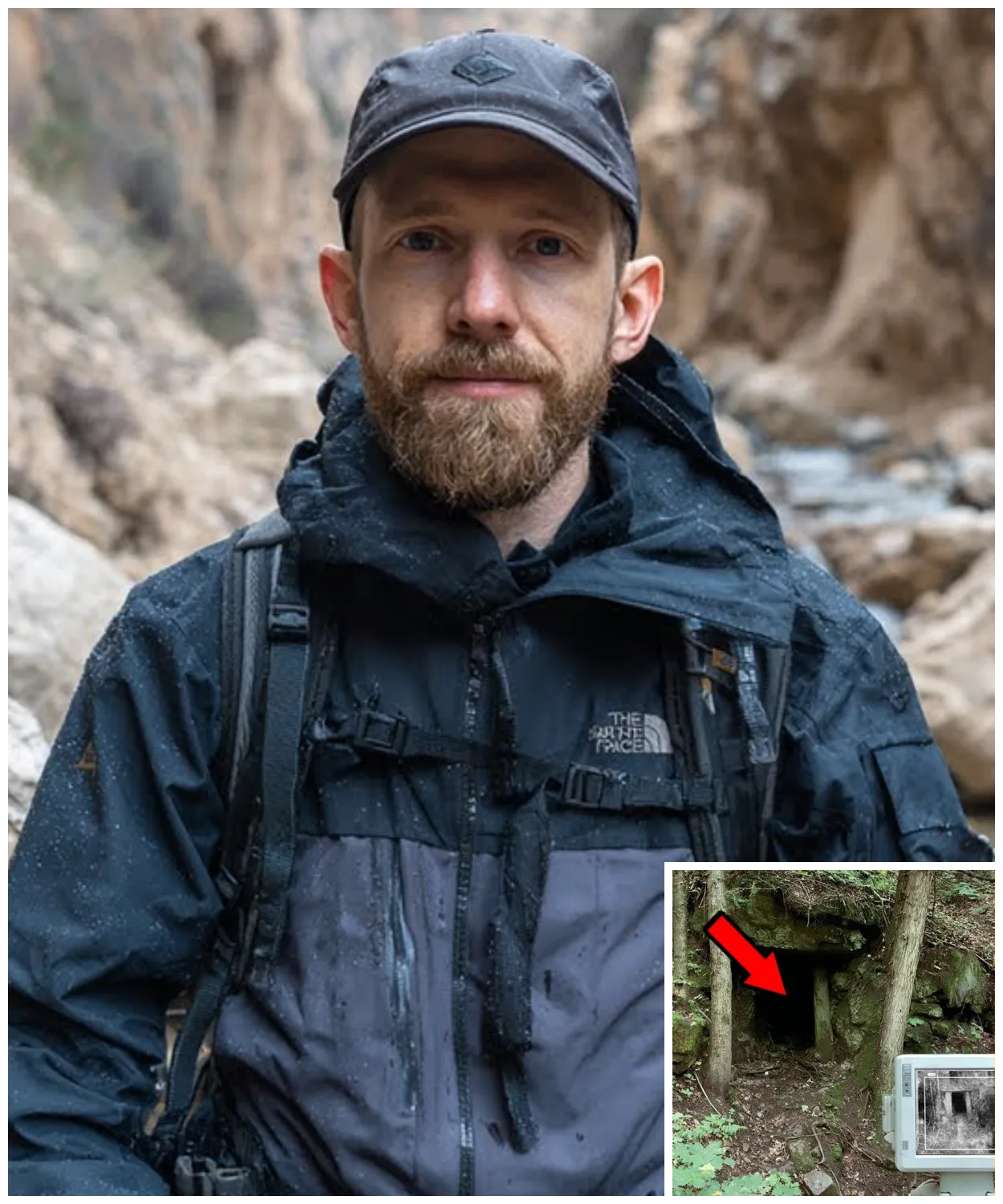

In October of that year, a hunter named Robert Henderson went deer hunting in the San Juan Mountains.

Robert was 52 years old and an experienced hunter who spent several weeks in the mountains every fall.

He knew the area well, but this time he decided to go to a section he had never been to before.

It was a dense forest on the northern slope, difficult to access with many rock ledges and caves.

Robert was looking for a place where deer might graze and accidentally stumbled upon the entrance to a small cave covered by bushes and fallen trees.

He decided to look inside to see if bears were using the cave for hibernation.

If there was a bear den there, it meant it would be better not to set up camp in that area.

Robert turned on his flashlight and went inside.

The cave was small, about 10 m deep, with a low ceiling, and an uneven floor covered with stones and dry leaves.

It smelled damp and musty.

In the depths of the cave, he saw bones.

This was not surprising, as bears often dragged the remains of their prey there.

But when Robert got closer and shown his flashlight, he saw a human skull.

The skull lay among other bones partially covered with earth and leaves.

Robert immediately realized that these were not animal bones.

The shape of the skull, the eye sockets, the jaw, everything was clearly human.

He took a step back, his heart beating faster.

His first thought was that someone had died here many years ago, perhaps lost and frozen or starved to death, and that a bear had then dragged away the remains.

But when Robert bent down and looked more closely at the skull, he noticed holes, lots of holes.

They were all over the surface of the skull, round, smooth, clearly from bullets.

Robert did not touch the skull.

He left the cave, marked the coordinates on his GPS, and immediately contacted the local sheriff’s office.

He realized that he had stumbled upon something serious and that it was no longer his business.

A few hours later, a team from the sheriff’s office, forensic experts, and a medical examiner arrived at the scene.

They cordined off the cave and began a thorough examination.

In addition to the skull, they found other bones scattered across the cave floor.

ribs, vertebrae, leg, and armbbones partially damaged by time and animals.

All of these were human remains and all belonged to one person.

The skull was sent for examination.

The forensic expert confirmed that it was a man about 30 years old and that the remains had been lying in the cave for 15 to 20 years, but the main discovery was in the holes.

The expert counted 22 bullet wounds on the skull.

All the shots were fired from a 22 caliber rifle.

This was a small caliber, often used for hunting small game or for target practice.

The bullets did not penetrate the skull completely, but got stuck or ricocheted, leaving characteristic holes.

The expert also noted that the shots were fired from close range, most likely from a distance of 5 to 15 m.

This was not an accidental hit or a hunting accident.

It was a deliberate shooting of a person.

The next step was to identify the deceased.

The remains were incomplete, but sufficient for DNA analysis.

The Colorado missing person’s database stored DNA samples from all unsolved cases, including that of Dan Morris.

The results came back in 2 weeks.

The match was a perfect one.

The skull and bones belong to Dan Morris, a mechanic from Durango, who had disappeared 18 years ago in June 1997.

This discovery completely changed the case.

What had been considered an accident or a loss in the mountains for 18 years had now turned into a murder.

And not just a murder, but something much more disturbing.

22 shots to the head were not the result of a quarrel or self-defense.

it was an execution or something similar.

The Llata County Sheriff ordered the investigation to be reopened and a special team to be set up to deal exclusively with this case.

Ballistic analysis became the key focus.

Experts studied the nature of the holes in the skull, the angle of entry of the bullets, and the firing distance.

All the shots were fired from the same weapon, a 22 caliber rifle.

This caliber was popular among hunters and sport shooters in Colorado.

But the number of shots and their location indicated something unusual.

The shooter did not simply kill Dan.

He shot him again and again, even after the victim was already dead.

It was excessive, almost ritualistic.

Experts also noted that the remains were found in a bear cave.

This could mean that the body was left there deliberately to be destroyed by animals.

Bears often use caves as temporary shelters and may feed on kerrion if they find it nearby.

If the killer left the body at the entrance to the cave or dragged it inside, the bears could have finished the job by dragging away the bones and hiding the evidence.

It was a deliberate attempt to dispose of the body so that it would never be found.

The investigation focused on finding the owner of a 22 caliber rifle that could have been used in the murder.

Several hundred such weapons were registered in the county and checking each owner would have taken months.

But the investigators had one lead.

Dan had disappeared in the Cole Creek Pass area.

His car had been found in a parking lot and his body had been discovered in a cave about 12 km from that location.

This meant that the killer either knew the area very well, was a local resident, or worked in the area.

Investigators began checking everyone who was involved in the search operation in 1997.

They dug up old reports, lists of search party members, call logs, and meeting records.

Among the searchers was Thomas Grave, a ranger who worked in the area and knew the mountains better than anyone.

His name came up again and again in the reports.

He was one of the most active participants in the search, suggesting new routes, coordinating groups, and checking hard-to-reach places.

Investigators decided to check whether Thomas Grave owned a 22 caliber rifle.

A query to the registered weapons database showed that yes, a Ruger Model 1022 rifle purchased in 1993 was registered in his name.

It was a standard rifle for hunting small game, light, accurate, with a 10 round magazine.

Thomas stated in the documents that he used it to shoot squirrels and rabbits.

This in itself was not proof, but it was a reason for a more thorough investigation.

Investigators asked Thomas for permission to examine the weapon for ballistic analysis.

He agreed without objection, saying he was willing to assist in the investigation in any way he could.

The rifle was confiscated and sent to the laboratory.

Experts conducted a series of test shots and compared the marks on the bullets with those extracted from the remains of Dan Morris’s skull.

The results came back 3 weeks later.

The match was a perfect one.

The bullets found in the skull had been fired from Thomas Graves rifle.

The marks on the casings, the microscopic scratches from the barrel, all pointed to this weapon being the one used to kill Dan Morris.

This was direct evidence linking Thomas to the crime.

Investigators obtained a search warrant for Thomas Graves home.

He lived in a small one-story house on the outskirts of Silverton away from the main roads and surrounded by forest.

The house was old, built in the 1960s with wooden walls and a crooked porch.

Thomas lived there alone with no neighbors nearby.

The nearest house was half a kilometer away on a dirt road.

The search began early in the morning on November 12th, 2015.

A group of six people, including investigators and forensic experts, arrived at Thomas’s house with a warrant.

Thomas was at home.

He opened the door calmly without panic and let everyone in.

He looked surprised, but not frightened.

He asked what was going on, and when they explained that ballistics had linked his rifle to the murder, he shook his head and said that was impossible.

that someone must have used his gun without his knowledge.

The interior of the house was modest and tidy.

There was a small living room with a sofa and a TV, a kitchen, a bedroom, and a bathroom.

Everything was clean and orderly with no signs of disorder or a hasty attempt to hide anything.

The investigators began to methodically examine each room, checking cabinets, drawers, and shelves.

In the living room, they found several books on wilderness survival, old hunting magazines, and a collection of knives on the wall.

The bedroom had ordinary furniture, clothes in the closet, nothing unusual.

But when the investigators went down to the basement, the picture changed.

The basement was small with concrete floors and walls, poorly lit with a single light bulb hanging from the ceiling.

Along the walls were metal shelves with boxes, tools, and old things.

In the corner was a workbench with a vice and a set of screwdrivers.

Everything looked like a normal basement where people store unnecessary things and sometimes repair something.

One of the detectives noticed an old TV in the corner of the basement.

It was a bulky CRT TV from the 1980s with a convex screen and a wooden case.

Next to the TV was a VHS VCR.

This was strange because there was already a modern TV in the living room.

Why keep an old TV and VCR in the basement if they weren’t being used? The forensic investigator turned on the TV and VCR.

There was a cassette inside the VCR.

He pressed the play button and an image appeared on the screen.

The quality was poor, the image was jerky, and there was interference in places, but it was clear enough to make out what was happening in the recording.

The screen showed a forest.

The camera was moving.

Apparently, the operator was walking, holding the camera in his hand.

You could hear breathing, the rustling of leaves underfoot, the crackling of branches.

The camera turned from side to side, filming trees, bushes, and rocks.

Then a person appeared in the frame.

A man in hiking clothes with a backpack on his back was running between the trees.

He looked back, his face pale, panic in his eyes.

He stumbled, fell, got up, and continued running.

The camera followed him.

The cameraman took his time, walking at a measured pace, but not falling behind.

You could hear the cameraman breathing heavily, sometimes laughing.

He was saying something.

His voice was low, calm, almost cheerful.

The words were indistinct due to the poor quality of the recording, but the tone was obvious.

It was a game for him, a hunt.

The recording continued.

The man in the frame continued to run, the camera following him.

Sometimes the man would stop, hide behind a tree, and try to catch his breath.

The camera moved closer, slowly, methodically.

Then a shot rang out.

the sound loud and sharp even on the old recording.

The man cried out, grabbed his leg or arm, and started running again.

The camera stopped for a few seconds, then started moving again.

This was repeated several times.

Shots, screams, running.

The man in the frame was getting slower and slower.

He was limping.

Blood was running down his clothes.

He fell, got up, tried to continue, but his strength was leaving him.

The camera was getting closer and now his face was visible in closeup.

It was Dan Morris.

His face was contorted with pain and fear.

His lips were moving.

He was saying something, perhaps asking for help, but the sound was indistinct.

Then the camera moved back a few meters.

A hand with a rifle appeared in the frame.

A series of shots rang out, one after another, quickly, methodically.

Dan fell and did not move.

The camera moved closer, filmed his body on the ground.

Then the image went black.

The recording ended.

The room was silent.

The investigators stared at the black screen, unable to utter a word.

They had just seen a man being murdered, filmed by the killer himself.

This was not just evidence.

It was a full confession, documentary proof that Thomas Grave had killed Dan Morris.

And he didn’t just kill him.

He hunted him down, chased him through the woods like an animal, wounded him again and again, prolonging his agony, filming it all on camera as a trophy.

One of the investigators rewound the tape and played it again.

They had to make sure it wasn’t a mistake, that they had understood everything correctly.

The recording repeated, the same images, the same sounds, the same ending.

This time, the investigator turned up the volume and listened to the words spoken by the cameramen.

The voice was clearly male with a slight accent characteristic of the locals.

The words were fragmented, but some phrases could be made out.

At the beginning of the recording, when the camera had just started following Dan, the cameraman said something like, “Come on, run.

Show me what you can do.” Then, after the first shot, hit him in the leg.

Good shot.

Later, when Dan was barely standing, you lasted longer than I thought.

And at the very end, before the last series of shots, a phrase that made everyone in the room freeze.

Hunting humans, the only real hunt.

These words were spoken clearly and calmly without emotion as a statement of fact.

For Thomas Grave, it really was a hunt, just like hunting deer or bear.

Only the prey was different.

For him, a human being was simply a target, an object to be tracked down, wounded, and killed.

The video recording was his trophy, proof of his skill, something he could return to again and again, reviewing his victory.

Investigators removed the tape from the tape recorder and packed it away as evidence.

They continued searching the basement and found several more tapes in a box on a shelf.

There were five tapes in total, all labeled with dates.

The first tape was dated June 1997.

It was the recording with Dan Morris.

The other four cassettes were dated earlier years, 1993, 1994, 1995, and 1996.

Each cassette was labeled by hand in neat handwriting.

The investigators did not watch the rest of the tapes on the spot.

They took everything away to the station for further analysis.

But it was already clear that Dan Morris was not Thomas Graves only victim.

Four tapes meant four more people, possibly four more unsolved cases of missing persons.

Thomas had been hunting people for years and no one knew about it.

Thomas Grave was arrested that same day.

He was taken to the station and charged with the murder of Dan Morris.

He did not resist, did not try to escape, did not demand a lawyer.

He just sat in the interrogation room, calm, almost indifferent.

When the investigator showed him a still frame from the video showing Dan’s face, Thomas looked at the image and nodded.

He said, “I remember him.

He was a good runner.

Lasted almost 2 hours.

No emotion, no remorse.” He talked about murder the way other people talk about fishing or going to the store.

For him, it was a normal thing, a part of his life that he was proud of.

The investigators began reviewing the rest of the videotapes.

Each recording showed the same picture, a man or woman in the woods, running, wounded, dying in front of the camera.

Thomas hunted tourists who came to the mountains alone without witnesses, without contact with the outside world.

He tracked them down, waited for the right moment, then began his game.

He gave them a chance to escape, wounded them to prolong the hunt, filmed everything on camera, and then finished them off with a shot to the

News

Six Cousins Vanished in a West Texas Canyon in 1996 — 29 Years Later the FBI Found the Evidence

In the summer of 1996, six cousins ventured into the vast canyons of West Texas. They were last seen at…

Sisters Vanished on Family Picnic—11 Years Later, Treasure Hunter Finds Clues Near Ancient Oak

At the height of a gentle North Carolina summer the Morrison family’s annual getaway had unfolded just like the many…

Seven Kids Vanished from Texas Campfire in 2006 — What FBI Found Shocked Everyone

In the summer of 2006, a thunderstorm tore through a rural Texas campground. And when the storm cleared, seven children…

Family Vanished from Stillwater Lake Texas in 1995 — 27 Years Later FBI Found Box with Clothes

In the summer of 1995, the Whitlock family vanished without a trace during their weekend retreat at Stillwater Lake. Their…

Family Vanished from Stillwater Lake Texas in 1995 — 27 Years Later FBI Found Box with Clothes

In the summer of 1995, the Whitlock family vanished without a trace during their weekend retreat at Stillwater Lake. Their…

SOLVED: Arizona Cold Case | Robert Williams, 9 Months Old | Missing Boy Found Alive After 54 Years

54 years ago, a 9-month-old baby boy vanished from a quiet neighborhood in Arizona, disappearing without a trace, leaving his…

End of content

No more pages to load