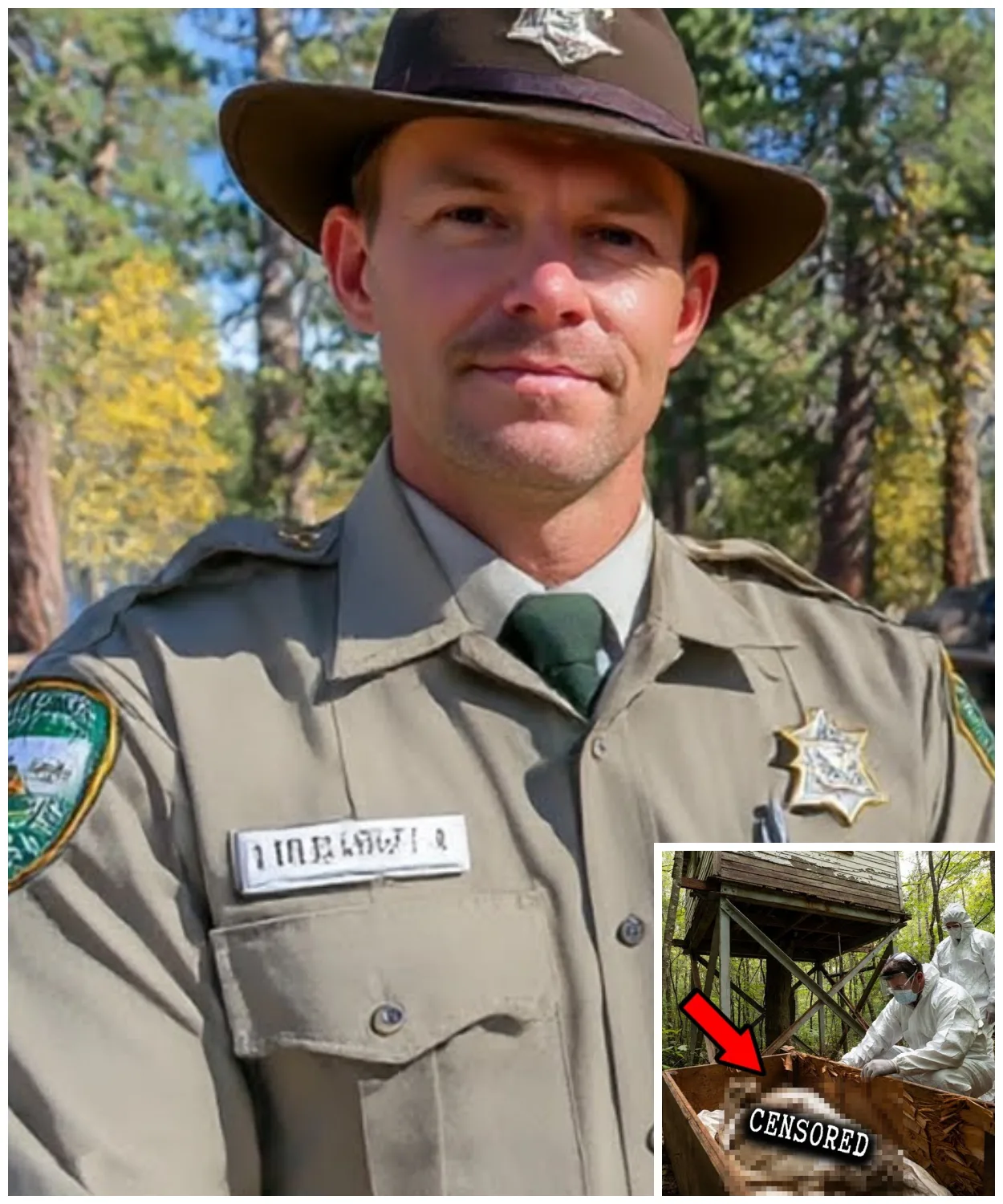

In August 1980, Ranger Robert Ames went on a routine patrol in one of the most isolated areas of the Tongas National Forest in Alaska and never returned.

His disappearance remained a mystery for three decades until in 2010, a construction crew began dismantling an old observation tower and discovered human remains encased in concrete.

Forensic tests confirmed that it was Robert Ames and that his disappearance was not accidental.

The Tongas National Forest covers 68,000 square kilmters in southeastern Alaska.

It is the largest national forest in the United States, an area so vast that most of it remains inaccessible to ordinary tourists.

Thousands of kilometers of unpaved roads, mountain ranges, fjords, dense coniferous forests where the trees grow so thickly that sunlight barely reaches the ground.

The climate here is harsh even in summer.

It rains almost constantly.

Fog covers the valleys for days on end, and the temperature rarely rises above 15°.

In winter, snow can lie until May, and in remote areas, communication is intermittent or non-existent.

Robert Ames was 39 years old when he disappeared.

He was born in Oregon, served in Vietnam from 1968 to 1970, and returned home with a knee injury and several medals for bravery.

After demobilization, he moved to Alaska, seeking peace and quiet and distance from people.

He got a job with the Forest Service, starting as a junior ranger.

And after a few years, he got a permanent position and his own patrol area.

Colleagues described him as a calm, reliable person who knew the forest well and rarely broke the rules.

He was married, his wife worked as a nurse in the city of Ketchacan, and they had no children.

Ames worked as a ranger for six years and was responsible for an area in the Misty Fjords, one of the most inaccessible and dangerous routes in Tongas.

The area was located at an altitude of 300 to 900 m above sea level and included several mountain trails, old patrol huts, and forest fire observation points.

It could only be reached on foot or by helicopter as the nearest road ended 20 km from the border of the area.

Rangers usually spent several days there checking the condition of the trails, recording signs of illegal logging, and monitoring the movement of wild animals.

In the summer of 1980, construction of a new observation tower began on the Ames section.

The old one had burned down 2 years earlier after being struck by lightning, and the park service had allocated funds for the construction of a new structure.

The tower was built at an altitude of about 600 m on a rocky outcrop with a good view of the valley and the surrounding ridges.

The contractor was a Canadian company that specialized in construction in hard-to-reach places.

The project manager was Martin Glover, a 50-year-old engineer from British Columbia who was working in Alaska for the third season.

Ames regularly checked on the progress of construction.

It was part of his job.

He recorded the use of materials, monitored compliance with environmental standards, and prepared reports for management.

Relations with Glover were tense from the start.

Glover did not like anyone checking his work and considered rangers to be useless bureaucrats who only got in the way.

Ames, however, took his duties seriously and pointed out several violations.

improper waste disposal, tree felling outside the permitted area, and the use of materials that did not meet specifications.

At the end of July, Ames filed a formal complaint with the regional forest service office.

In the document, he described systematic violations by Glover’s construction company, overstating the amount of materials used in reports, illegally cutting down trees that were then sold to third parties, and failing to comply with safety regulations on the site.

The complaint was registered on July 28th, and a copy was sent to the company’s head office and the county sheriff’s office.

Glover learned of the complaint a few days later and was furious as later recounted by workers who were on site at the time.

On August 8th, Ames set out on another patrol.

The plan was standard.

Leave base camp around a.m., check the trails and huts along the route, inspect the construction site, and return in 2 days.

The route covered about 30 kilometers of mountainous terrain, including the ascent to the tower construction site.

Ames walked alone as usual.

He carried a backpack with food and equipment, a radio, a service weapon, a 38 caliber revolver, maps, a compass, and a first aid kit.

He was last seen at the construction site around noon on August 9th.

One of the workers, David Cole, later recalled that Ames was talking to Glover near the unfinished tower.

The conversation was brief.

Glover looked unhappy, waving his arms while Ames stood calmly, writing something in his notebook.

Then Ames walked away toward the ranger hut, which was about 200 m from the site.

Cole went back to work and didn’t pay any more attention to it.

Ames was supposed to get in touch on the evening of August 10th when he got back to base.

The connection did not come through.

The dispatcher tried to contact him by radio several times during the evening and night, but there was no response.

On the morning of August 11th, a helicopter with two rangers was sent to check.

They flew to the base camp, but Ames was not there.

The helicopter flew the entire route, checked the huts and the construction site, but found no trace of him.

The rangers landed near the hut on Ames’s plot.

The door was unlocked and everything inside looked normal.

The bed was made, the table was clean, and Ames’s radio was lying on the table.

The radio was turned off, but in working order, the battery charged.

Ames’s backpack hung on a hook by the door.

Inside were leftover food, a thermos, and a change of clothes.

The revolver was gone, the holster empty.

The notebook in which Ames usually recorded his observations was also missing.

The rangers searched the area around the cabin.

There were no signs of a struggle, no damage, no indication that Ames had left in a hurry.

There were footprints from his boots on the ground leading from the cabin to the trail toward the construction site.

But then the trail disappeared on the rocky section.

The weather had been changeable in recent days with intermittent rain and the ground on the trails was wet but firm making it difficult to find footprints.

The search began immediately.

A group of eight rangers and volunteers was organized and they combed the entire area within a 5 km radius of the last known location.

They checked trails, ravines, thicket and cliffs.

A helicopter flew over the area for three days in a row, but visibility was poor due to fog.

Dogs were brought in, but Ames’s tracks ended on a rocky trail near the construction site and were not found again.

All the workers at the construction site were questioned.

Glover said he saw Ames on the afternoon of August 9th.

They talked about the work schedule.

Everything was fine.

Ames left in the direction of the hut.

He was not seen again.

The workers confirmed that Ames was on site during the day, then left and no one else saw him.

All the workers remained on site until the evening of August 10th, working late because the weather was deteriorating and they needed to finish pouring the foundation for the tower.

Glover was also there all day as witnesses confirmed.

The county sheriff came in person, inspected the site, and talked to people.

The official version leaned toward an accident.

Ames could have fallen off a cliff while on patrol, could have gotten lost in the fog, could have encountered a bear and been attacked.

This happened in Tongas.

People disappeared.

Bodies were found months later or not at all.

It was a wild area, dangerous conditions.

There was always a risk.

The search continued for 2 weeks, then was called off.

The case was registered as a disappearance under unclear circumstances.

Ames’s wife did not believe it was an accident.

She said that her husband was an experienced ranger, knew the forest, was cautious, and would not have taken any risks.

She insisted on continuing the investigation, wrote letters to various authorities, and demanded that the construction company and Glover himself be investigated, but there was no evidence.

Glover had an alibi.

The workers confirmed his story, and nothing suspicious was found at the site.

Construction of the tower continued.

Glover finished pouring the foundation in mid August, a week after Ames disappeared.

The concrete foundation was a massive structure 3 m high, 4 m in diameter, reinforced with steel rods.

A wooden observation tower with a staircase and a platform at the top was erected on this foundation.

The work was completed at the end of September.

Glover received his payment, closed the project, and left Alaska in early October, returning to Canada.

He did not work in Alaska again, moving on to other projects in British Columbia.

Years passed, and Ames’s case remained unsolved.

His wife waited 5 years, then filed papers to have her husband declared dead.

She received a small insurance payout and moved to another state.

Ames’s colleagues remembered him, but over time his story became one of many.

Just another person lost in the vast forests of Alaska.

The tower built by Glover served the rangers faithfully for 30 years.

It was used to monitor fires, conduct animal censuses, and as a radio communication point.

In 2010, the park service decided to renovate the tower.

The wooden structures had rotted.

The staircase had become dangerous and major repairs were needed.

A local construction company from Ketchacan was hired as the contractor.

The crew arrived on site in early July and began dismantling the old wooden elements.

The plan was to preserve the concrete foundation and build a new structure on top of it.

On July 23rd, workers began inspecting the condition of the concrete in the base.

They used drills to take samples and determine whether the foundation needed to be reinforced or whether it was possible to build on the existing one.

The first few drills went smoothly.

The concrete was dense and of good quality.

The fourth drill bit got stuck at a depth of about 1 meter.

The worker tried to pull it out but failed.

They called the foreman and decided to widen the hole to see what was blocking it.

They widened the hole with a jackhammer and removed the pieces of concrete.

Inside, there was a wooden surface.

At first, they thought it was part of the old formwork that had been forgotten during pouring.

But when they cleared away more concrete, it became clear that it was not formwork.

It was a wooden box about a meter by a meter in size built into the center of the tower’s base.

The foreman suspended work and contacted the park service management.

The situation seemed strange.

A wooden box inside a concrete base made no technical sense.

It was not standard construction practice.

Management instructed them to continue carefully opening it, but to record everything on camera and not to damage the contents if there was anything there.

The workers continued to dismantle the concrete around the box.

The work proceeded slowly using hand tools so as not to damage the wood.

By the evening of July 23rd, the upper part of the box had been freed.

The lid was nailed shut, and the wood had darkened from age and moisture, but it was fairly well preserved thanks to the protection of the concrete.

Remnants of markings were visible on the lid, faded letters, and a logo.

One of the workers made out the inscription, National Park Service, Alaska.

On July 24th, a representative of the park service and an officer from the local police department arrived at the site.

They decided to open the box on the spot.

They carefully removed the lid.

The boards were damp but still intact.

Inside the box was a tarpolin rolled up and tightly packed.

The tarpollen also had the park service markings.

They unfolded the tarpollen and found human remains inside.

The skeleton was lying in a curled position, knees pulled up to the chest, arms crossed.

The bones were in relatively good condition, protected from decay, and animals by the concrete.

Next to the remains were some items, fragments of clothing, a belt with a buckle, boots, and an empty holster for a revolver.

A small notebook with a waterproof cover was visible on the ribs.

The pages were stuck together, but not completely destroyed.

There was another item, a metal tag on a chain, an employee ID card.

When it was cleaned, the name became visible.

Robert Ames, Ranger, National Park Service.

The police cordined off the area and called in forensic experts from Juno.

The remains were carefully removed from the box and taken to the morg for examination.

The box and all its contents were sent for analysis.

News of the discovery quickly spread among park service employees.

The old-timers remembered the story of Ames’s disappearance 30 years ago.

The initial examination of the remains was conducted on July 26th.

The medical examiner determined that the skeleton belonged to a man between the ages of 35 and 45, approximately 178 cm tall.

This matched Ames’s description.

But the most important discovery was made during the examination of the skull.

There was an entry wound from a bullet in the back of the head.

It was a small neat hole characteristic of a shot from a medium caliber revolver at close range.

There was no exit wound.

The bullet remained inside the skull.

Upon careful examination of the remains and the contents of the box, the forensic experts found the bullet.

It was lying at the bottom of the box under the remains, deformed but suitable for analysis.

The examination showed that it was a 38 special caliber bullet, the standard ammunition for Rangers service revolvers in 1980.

Ames’s revolver was never found, either during the initial search or now.

DNA samples were taken from the femur and sent for analysis.

For comparison, biological samples were requested from Ames’s ex-wife, who was still alive and living in Washington State.

The woman agreed to the test.

The results came back in 3 weeks.

The match was 99%.

The remains belonged to Robert Ames.

The case of the missing ranger from 1980 was officially reclassified as a murder investigation.

A special task force was created headed by Detective Thomas Marlo of the Alaska State Police.

Marlo was 48 years old, had been with the police for 23 years, and specialized in unsolved cases.

He began by studying all the materials from 30 years ago, search reports, witness statements, and construction company documents.

The main theory took shape quickly.

Ames was killed by someone who had access to the construction site and the opportunity to embed the body in the concrete foundation of the tower.

The foundation was poured in mid August 1980, a few days after Ames’s disappearance.

It was logical to assume that the murder took place before the foundation was poured and that the body was placed in a box and covered with concrete.

Marlo requested all the archival documents related to the construction of the tower.

It turned out that the foundation was poured on August 10th, 1980, the very day Ames went missing.

Work began early in the morning and continued until late in the evening because the concrete had to be poured in one go to ensure the strength of the structure.

Glover personally supervised the process and there were seven workers on site.

The detective began searching for the workers who had been on site 30 years ago.

Two had died.

One had moved to an unknown location, and four were found and interviewed.

Their testimonies were similar.

On August 10th, they worked from morning to evening pouring concrete with Glover nearby the entire time.

No one saw anything suspicious, but one of the workers, David Cole, the same one who saw Ames on August 9th, added an interesting detail.

He recalled that on the morning of August 10th, Glover asked all the workers to prepare the formwork on the opposite side of the site while he himself remained near the central part of the foundation for about an hour.

He said that the reinforcement needed to be checked, that it was technical work, and the workers were not needed.

Cole didn’t think much of it at the time, but now the details seemed important.

It was in the central part of the foundation that the box with the body was found.

If Glover stayed there alone for an hour, he had time to place the box in the formwork before the concrete was poured.

Marlo found another clue in the archives.

Ames’s complaint from July 28th, 1980 was officially registered, but the investigation into it never began.

After Ames disappeared, the case was closed.

It was decided that since the complainant was missing, there was nothing to investigate.

But the complaint itself contained specific allegations against Glover, overstating the volume of materials, illegal logging, and selling timber to third parties.

If the investigation had taken place, Glover could have lost his contract, and faced criminal charges.

The detective began searching for Martin Glover.

It turned out that the man was still alive, 81 years old, living in a small town in British Columbia.

Retired.

After Alaska, he worked on various construction projects in Canada, and retired in 2005.

He lived quietly with no problems with the law and no complaints.

On September 21st, 2010, at the request of their colleagues in Alaska, Canadian police detained Glover for questioning.

They brought him to the station and explained the situation.

Glover denied everything.

He said he did not kill Ames, did not know how the body got into the base of the tower and had nothing to do with it.

He said that he had last seen Ames on the afternoon of August 9th when Ames went into a hut and that they had not met since.

He had been working on the site on August 10th, pouring concrete, and nothing unusual had happened.

Marlo flew to Canada and personally conducted several interrogations of Glover.

The man remained confident, did not change his testimony, and demanded a lawyer.

There was no direct evidence of his guilt, only circumstantial evidence, and a logical construction of the version.

Something else had to be found.

The detective returned to the notebook found in the box with the body.

The notebook was sent for examination and experts attempted to restore the entries.

The paper was damp, the ink had smudged, and many pages were stuck together.

However, several pages were separated and read under special lighting.

One of the pages contained an entry dated August 9th, 1980.

Ames described a conversation with Glover on the set.

The text was fragmentaryary, but the meaning was clear.

Glover threatened Ames, saying that the complaint would ruin his business, that Ames would regret it.

The last line of the entry read, “Glover said, see you tomorrow morning at the site.

We need to have a serious talk.” This was important evidence.

Ames had planned to meet with Glover on the morning of August 10th, the day the concrete was poured.

Perhaps the meeting took place and the murder occurred during it.

Marlo returned to questioning the workers.

He asked if anyone had seen Ames on the site on the morning of August 10th.

Cole remembered another detail.

Early in the morning, around , he saw a figure near the rers’s hut, but he was too far away to see the person’s face.

He thought it was one of the workers.

Then he didn’t think much of it.

The hut was 200 m from the site, and the entire construction area was clearly visible from there.

If Ames had come there on the morning of August 10th to meet with Glover, they could have met somewhere between the hut and the site away from the eyes of the workers.

The detective requested data on the weather that day.

On the morning of August 10th, 1980, there was thick fog with visibility less than 50 m.

The fog did not lift until .

This provided an opportunity for covert movement.

Glover could have met with Ames in the fog and no one would have seen them.

Marlo constructed a detailed version of events.

On August 9th, Ames and Glover talked on the site and the conversation was tense because of the complaint.

Glover suggested meeting the next morning to discuss the situation.

Ames agreed and wrote it down in his notebook.

On the morning of August 10th, in the fog, they met somewhere between the hut and the site.

An argument ensued.

Glover grabbed Ames’s revolver and shot him in the back of the head.

Ames fell.

Glover took his body and placed it in a wooden box.

He used a standard toolbox that was on the site.

He closed the box and wrapped it in tarpollen to prevent concrete from seeping inside.

While the workers were preparing the formwork at the other end of the site, Glover placed the box in the center of the future foundation between the reinforcing bars.

Then the concrete was poured and the box disappeared under tons of concrete.

The version was logical, but evidence was needed.

The detective continued to work with his notebook.

The experts were able to recover several more entries.

One entry from August 7th described how Ames had found a cache of illegally cut timber in a forest 3 kilometers from the site.

The timber was marked with Glover’s company logo.

Ames photographed the cash, planning to attach the photos to his complaint, but no camera was found among Ames’ belongings, either then or now.

Marlo requested all materials related to the Ames case from 30 years ago, from the park service archives.

The case included the rers’s personal belongings, which had been seized from his cabin, a radio, a backpack, and clothing.

The camera was not there, but the inventory of items indicated that Ames usually carried a Nikon camera with him, which his colleagues knew.

The camera disappeared with him.

If Glover killed Ames, he had to get rid of the camera with the compromising photos.

The detective decided to check if the camera had turned up anywhere later.

He requested databases on the theft and sale of photographic equipment in Canada and the United States for the period from August 1980 to December of the same year.

The search yielded no results.

The camera was not registered.

But Marlo did not give up.

He studied Glover’s financial records for that period.

He discovered something interesting.

In October 1980, immediately after leaving Alaska, Glover deposited a large sum of cash into his account at a Canadian bank.

The amount was $28,000.

During questioning, Glover explained that this was payment for the Alaska project, but the document showed that the official payment had gone through the company, not to him personally in cash.

The detective suggested that the 28,000 could have been proceeds from the sale of illegally harvested timber.

This was precisely what Ames accused Glover of in his complaint.

He requested data on timber sales in the region in August September 1980.

He found several transactions, one of which looked suspicious, the sale of a large batch of timber to a company in Vancouver.

The seller being a front company that had existed for only 3 months and was closed immediately after the transaction.

The director of the company was listed as a man named Martin Gleason.

But when Marlo checked the data, it turned out that this was a pseudonym and the documents were fake.

Comparing the dates and amounts, the detective concluded that Glover was indeed involved in the illegal logging and sale of timber using a front company and had received $28,000 for it.

Ames found out about this, filed a complaint, and Glover realized that his scheme had been exposed and decided to eliminate the witness.

With this information, Marlo returned to questioning Glover.

Several sessions passed without result.

The man denied everything, saying that the detective was building theories without evidence.

But during the fourth interrogation, when Marlo presented financial documents and information about the front company, Glover began to get nervous.

His lawyer advised him to remain silent, but Glover couldn’t hold out.

He said he wanted to tell the truth.

The confession was recorded on video on October 28th, 2010.

Glover spoke slowly, his voice trembling, his hands shaking.

He said that he had indeed been involved in illegal logging.

It was a way to earn extra money as contracts in Alaska paid little.

When Ames filed a complaint, Glover realized that everything would collapse.

He would lose his contract.

There would be legal proceedings, possibly prison.

He decided to talk to the ranger to try to come to an agreement.

On August 9th, they met at the site and Glover offered money for Ames to withdraw his complaint.

Ames refused, saying that it was his job and he would not turn a blind eye to violations.

Glover became angry and threatened that Ames would regret it.

Ames replied that an inspector from headquarters would arrive the next morning to inspect the site based on his complaint.

This was not true, but Glover believed him.

Glover spent the night awake thinking about what to do.

He understood that if the inspector arrived, everything would be revealed.

He decided to meet with Ames in the morning to try to negotiate again or intimidate him.

Around in the morning on August 10th, he came to the rangers hut.

Ames was there getting ready to go out on the trail.

Glover said they needed to have a serious talk and suggested they move away from the hut so the workers wouldn’t hear them.

They walked about 200 m along the trail toward the site.

There was thick fog.

Visibility was almost zero.

Glover offered money again, suggested leaving the site altogether, shutting down the project.

Ames refused, saying that the complaint had already been filed.

The inspector would come anyway.

Nothing could be changed.

Glover lost his temper and started shouting.

Ames turned to leave.

Glover saw the revolver on the Ranger’s belt and without thinking pulled it out of its holster.

Ames turned at the sound and tried to take the weapon back.

A short struggle ensued, but Glover was bigger and stronger.

He snatched the revolver and took a step back.

Ames told him not to do anything stupid that it would only make the situation worse.

Glover aimed at him, his hand trembling, panic in his head.

Ames turned his back and said he was going back to the cabin to call for help.

He took a few steps.

Glover fired.

The bullet hit the back of his head and Ames fell face down without making a sound.

Glover stood with the revolver, not understanding what he had done.

Then the panic intensified.

He realized that he had committed murder, that now it was not just the loss of a contract, but life in prison or execution.

He had to hide the body, make sure no one would find it.

He looked around in the fog.

No one was in sight.

No one could be heard.

The workers weren’t due to arrive on site until 8 in the morning.

He had time.

He returned to the site, picked up one of the wooden tool boxes, an empty box measuring 1 m by 1 m.

He brought it to the place where the body lay.

He dragged the body into the box, having to bend it to make it fit.

He closed the lid and nailed it shut.

He found a piece of tarpollen marked with the park service logo lying near the hut and wrapped it around the box to prevent concrete from seeping in.

He dragged the box to the center of the site where the formwork for the tower foundation was already in place.

The builders had installed the rebar frame the night before and there was an empty space inside before the concrete was poured.

Glover placed the box in the center of the frame and secured it with wire between the bars so that it would not move during pouring.

He threw a few metal scraps on top to camouflage the box.

By 7 in the morning, he was finished and the fog began to dissipate.

He took Ames’s revolver, notebook, and camera with him.

He left the radio in the hut to give the impression that Ames had returned there and left.

By 8 in the morning, the workers began to arrive.

Glover met them and told them that today they would be pouring the foundation, which would take all day.

He assigned tasks so that no one would come close to the center of the formwork until he had finished preparing it himself.

Around in the morning, concrete mixers began to arrive.

The pouring began, and the concrete gradually filled the formwork, covering the rebar and the box in the center.

By evening, the foundation was completely poured, 3 m high, and the box was under a ton of concrete about a meter deep from the top surface.

The next day, the formwork was removed, and the foundation looked monolithic with no signs that there was anything inside.

When the search for Ames began, Glover behaved calmly, answered questions, and gave testimony.

He was confident that the body would never be found.

who would break a newly built concrete foundation.

The plan worked, the search was called off, and the case was closed.

Glover finished building the tower, got paid, and left for Canada.

He threw the revolver and camera into the ocean from the ferry on the way.

He burned the notebook.

He lived for 30 years, thinking that everything was in the past until the police came with the news that the remains had been found.

He realized that it was over, that there was no point in denying it anymore.

Detective Marlo listened to the confession and asked clarifying questions.

Glover answered everything, making no attempt to minimize his guilt or justify himself.

He said he had lived with this burden for 30 years, thinking every day about what he had done.

He couldn’t sleep properly and saw a in his dreams.

The confession was almost a relief.

After the confession was recorded, the legal process began.

Glover was officially charged with first-degree murder.

The Canadian authorities agreed to extradite him to the United States for trial.

In December 2010, he was transferred to Alaska and placed in custody pending trial.

The trial began in March 2011.

The defense tried to prove that the murder was unintentional, that Glover acted in the heat of passion, that he did not plan to kill Ames.

But the prosecution presented evidence to the contrary, the concealment of the body, a well-thoughtout plan to encase it in concrete, and the destruction of evidence all pointed to cold-blooded calculation after the murder.

The jury deliberated for 2 days.

The verdict was guilty of first-degree murder and concealment of a body.

Considering the defendant’s age and confession, the prosecution did not seek the death penalty.

The judge sentenced Glover to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

Ames’s ex-wife attended the sentencing hearing.

She was already 72 years old and did not speak in court, but sat in the gallery and listened.

After the sentencing, she gave a short interview to a local newspaper.

She said she had waited 30 years for answers and had always known that her husband had not simply disappeared.

She said that justice had prevailed, albeit too late.

Robert had been a good man, an honest ranger, doing his job, and that had killed him.

Ames’s remains were buried in the Ketchin Cemetery in April 2011.

The funeral was attended by colleagues from the park service, several old friends, and his ex-wife.

It was a small ceremony with short speeches about a man who served his country in the war and died while performing his duty in peace time.

The National Park Service installed a memorial plaque on the new observation tower which was built after the reconstruction.

The plaque bears the name of Robert Ames, his years of life, and words about how he gave his life protecting the forest from criminals.

The tower is now unofficially called Ames Tower and rangers use this name in radio communications.

The case led to changes in park service protocols.

Now rangers patrolling remote areas are required to check in every 12 hours rather than once every 2 days.

When constructing any facilities within park boundaries, a ranger must be present at all times rather than periodically.

All complaints of violations are given priority even if the complainant is unavailable for some reason.

Glover is serving his sentence in a maximum security prison in Anchorage.

He is now 95 years old in poor health and spends most of his time in the prison hospital.

His lawyers have filed several petitions for clemency on health grounds, but all have been rejected.

The prosecution believes that the severity of the crime and the 30-year coverup do not allow for mercy.

Detective Marlo received an award from the governor of Alaska for solving the 30-year-old case.

He said in an interview that it was one of the most difficult cases of his career because most of the witnesses had died or could not remember the details.

There was almost no physical evidence and everything depended on logic and patience.

But justice has no statute of limitations, and if there is even the slightest chance of solving a case, it must be pursued.

The story resonated with the Ranger community across the country.

Many remembered colleagues who had disappeared under unexplained circumstances in different years.

Several old cases were reopened and reinvestigations began.

Two cases were solved.

In one, remains were found in an abandoned mine, and in the other, a witness who had remained silent for 20 years out of fear was found.

The Tongas National Forest continues to operate with rangers patrolling the same routes as they did more than 30 years ago.

The Ames Tower stands in its place, still observing the forest, recording fires, and monitoring wildlife.

The new concrete foundation contains nothing but rebar and stones.

The workers who built it in 2011 joked grimly that now every time they pour concrete, they will check to make sure they haven’t forgotten to remove the tools from the formwork.

The exact location where Glover shot aims has never been determined.

Glover gave an approximate location somewhere between the hut and the clearing 200 m from both structures.

But in 30 years, the forest has changed.

The old landmarks have disappeared, and the trail has shifted.

Rangers sometimes walk along that trail, passing the spot where their colleague once fell.

Some stop and stand silently for a minute, paying tribute to a man who did his job honestly and paid for it with his life.

Ames’s camera, with the film containing photographs of illegally logged timber, was never found.

Glover claimed to have thrown it into the ocean, but divers searched the alleged location and found nothing.

Perhaps the current carried it away.

Or perhaps Glover was mistaken about the coordinates.

These photographs could have been direct evidence against him back in 1980 and could have saved Ames if the complaint had been investigated more quickly.

But history knows no subjunctive mood.

The Robert Ames case became one of the longest unsolved murders in Alaska’s history.

30 years from the crime to its discovery.

It showed that even a perfectly planned coverup can fail due to chance.

If the park service had not needed to renovate the tower, if they had decided to simply tear it down and build a new one elsewhere, the body would never have been found.

The concrete foundation could have stood for another 50 years, maybe a hundred.

Glover would have lived out the rest of his days in freedom, died in his bed, taking the secret to his grave.

But they decided to renovate the tower.

The drill got stuck in the concrete.

The workers found the box.

The experts identified the body.

The detective gathered evidence.

The criminal confessed.

Justice prevailed, although it did not help the victim, and the criminal was so old that prison became more of a hospice than a punishment for him.

The question remains, how many more cases like this are there that no one knows about? How many people have disappeared in national forests, mountains, and deserts, their bodies lying somewhere, walled up, buried, hidden so well that chance will not help? How many criminals live peacefully knowing that their secret is safely hidden and will never come to light? The National Park Service keeps statistics on missing persons in its territories.

The numbers are high.

Every year, hundreds of people disappear, most of whom are found alive or dead from natural causes.

But there remains a percentage of those who are never found.

Officially, they are recorded as lost, fallen off cliffs, swept away by rivers, or torn apart by animals.

Maybe that’s true.

Or maybe some of them lie in concrete foundations, wooden boxes, abandoned mines, waiting for their drill, their accidental discovery.

News

Six Cousins Vanished in a West Texas Canyon in 1996 — 29 Years Later the FBI Found the Evidence

In the summer of 1996, six cousins ventured into the vast canyons of West Texas. They were last seen at…

Sisters Vanished on Family Picnic—11 Years Later, Treasure Hunter Finds Clues Near Ancient Oak

At the height of a gentle North Carolina summer the Morrison family’s annual getaway had unfolded just like the many…

Seven Kids Vanished from Texas Campfire in 2006 — What FBI Found Shocked Everyone

In the summer of 2006, a thunderstorm tore through a rural Texas campground. And when the storm cleared, seven children…

Family Vanished from Stillwater Lake Texas in 1995 — 27 Years Later FBI Found Box with Clothes

In the summer of 1995, the Whitlock family vanished without a trace during their weekend retreat at Stillwater Lake. Their…

Family Vanished from Stillwater Lake Texas in 1995 — 27 Years Later FBI Found Box with Clothes

In the summer of 1995, the Whitlock family vanished without a trace during their weekend retreat at Stillwater Lake. Their…

SOLVED: Arizona Cold Case | Robert Williams, 9 Months Old | Missing Boy Found Alive After 54 Years

54 years ago, a 9-month-old baby boy vanished from a quiet neighborhood in Arizona, disappearing without a trace, leaving his…

End of content

No more pages to load