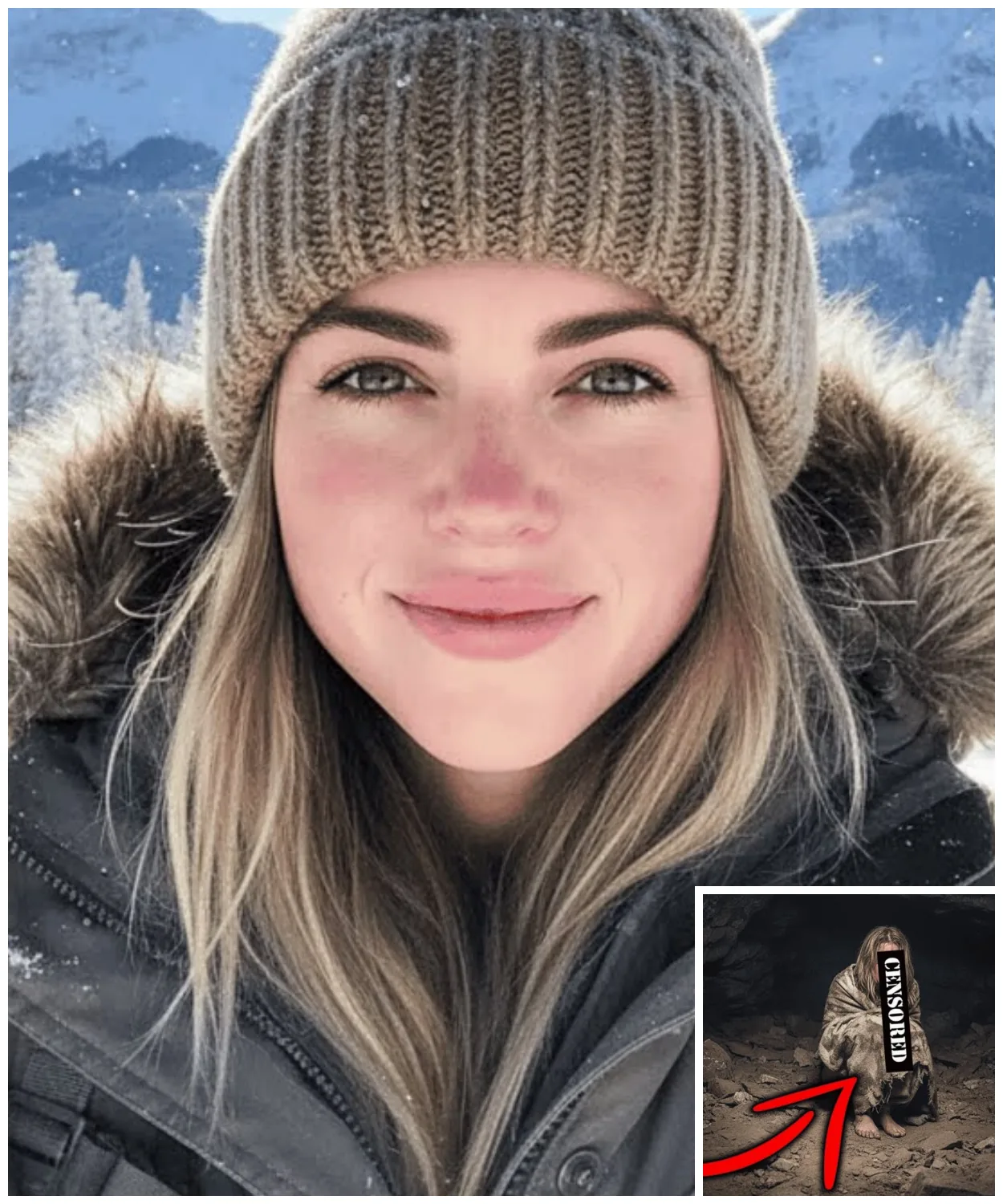

A 22year-old girl walked into the mountains one winter morning and simply vanished.

No trace, no answers, just silence.

For 60 days, that was the reality for one family in Colorado.

But what searchers eventually discovered in that cave defied every explanation? Why was she just staring? What had she survived in complete darkness? And why couldn’t she speak about those two months? What happened in that cave will leave you breathless.

January 14th, 2023.

The sun had barely crested the peaks of the San Juan Mountains.

When 22-year-old Brenda Joyce laced up her hiking boots in the small town of Silverton, Colorado, she told her roommate Melissa Harmon that she’d be back by sunset.

It was supposed to be a simple day hike along the Ice Lakes Trail, a route she’d walked a dozen times before.

Brenda was experienced, careful, and always carried extra supplies.

She kissed her golden retriever goodbye, grabbed her backpack, and headed out the door.

Melissa watched from the window as Brenda’s truck disappeared down the gravel road.

That was the last time anyone saw her alive and well.

By 9 that night, when Brenda hadn’t returned, Melissa’s concern turned to panic.

She called Brenda’s phone.

It went straight to voicemail.

She called again and again.

Nothing.

At , Melissa dialed 911.

The San Miguel County Sheriff’s Office dispatched a search team at First Light.

Deputy Nathan Cowwell led the initial sweep.

A veteran of mountain rescues with over 15 years of experience.

He knew these trails better than most.

Knew how quickly the weather could turn.

How easy it was to lose your bearings in a white out.

But when his team reached the trail head, where Brenda’s truck sat alone in the parking lot, something felt wrong.

Her vehicle was locked, untouched, covered in a thin layer of frost.

Inside they found her purse, her phone charger, and a halfeaten granola bar.

Her phone was gone.

Deputy Cowwell radioed back to base.

They needed more people.

Within hours, over 40 volunteers joined the search, calming through dense forest and rocky terrain.

They called her name until their voices went horsearo, but the mountain gave nothing back.

Search and rescue operations in the Colorado Rockies are no small undertaking.

The terrain is unforgiving with jagged cliffs, hidden crevices, and weather that can shift from clear skies to blizzard conditions in minutes.

Brenda’s family arrived from Denver that same evening.

Her mother, Patricia Joyce, was a composed woman, the kind who held herself together even when the world was falling apart.

But when she saw the search teams spreading out across the mountain side with flashlights and thermal imaging, her composure cracked.

She begged them to find her daughter.

She told them Brenda was strong, that she wouldn’t give up, that she had to be out there somewhere waiting for help.

Her father, Robert Joyce, stood beside her in silence, his jaw tight, his eyes scanning the darkening peaks.

He didn’t say much, but everyone could see the fear etched into his face.

By the third day, the search had expanded to cover over 12 square miles.

Helicopters flew overhead, scanning the snowcovered landscape with infrared cameras.

Ground teams used trained search dogs, following scent trails that led nowhere.

They found no footprints, no discarded items, no sign of struggle.

It was as if Brenda had simply evaporated into the mountain air.

Local news stations picked up the story.

Her picture appeared on every channel.

A brighteyed young woman with long brown hair and a warm smile.

Friends described her as adventurous but cautious, someone who respected the wilderness and never took unnecessary risks.

She worked as a substitute teacher and spent her weekends hiking, climbing, and photographing the landscapes she loved.

Everyone who knew her said the same thing.

Brenda wouldn’t just disappear.

Something had happened.

But what? The first week turned into two.

Then three.

The initial urgency of the search began to fade, replaced by a grim reality that everyone feared, but no one wanted to say aloud.

The chances of finding Brenda alive were dropping with each passing day.

Temperatures at night plunged below zero.

Even with her experience and supplies, surviving in those conditions for weeks seemed impossible.

Search coordinator Alina Martinez, a woman who had overseen hundreds of rescues, held a press conference on day 20.

She stood before a crowd of reporters and families, her voice steady but somber.

She explained that they were transitioning from rescue mode to recovery mode.

The words hit Patricia like a sledgehammer.

Recovery.

That meant they were looking for a body now, not a survivor.

She refused to accept it.

She organized her own search parties, recruited volunteers online, printed flyers, and plastered them across every town within a 100 miles.

But as the weeks stretched on, even the most dedicated volunteers began to lose hope.

The snow kept falling, covering any trace that might have existed.

The mountain, vast and indifferent, kept its secrets.

Then, on day 43, something strange happened.

A local man named Gregory Sutton, who lived in a cabin about 8 mi from the trail head, reported hearing sounds at night.

He described them as faint, almost like someone crying or moaning in the distance.

He’d gone outside with a flashlight, but saw nothing.

He assumed it was wildlife, maybe a mountain lion or an injured elk, but the sounds continued night after night, always around the same time.

He mentioned it to a friend who mentioned it to a deputy who decided it was worth checking out.

Deputy Cowwell and two others hiked out to Gregory’s property on day 45.

They listened, and sure enough, as dusk settled over the valley, they heard it, too.

It was faint, distant, and mournful, carried on the wind like a ghost.

The deputies looked at each other.

It didn’t sound like an animal.

They began walking in the direction of the sound, their flashlights cutting through the growing darkness.

The terrain grew rougher, the path less defined.

They climbed over fallen logs and navigated around icy boulders.

The sound grew louder, more distinct.

It was human.

Someone was out there.

Deputy Cowwell’s heart raced.

He shouted Brenda’s name.

The sound stopped.

For a moment, there was only silence.

Then it started again, weaker this time, almost like a whisper.

They moved faster, adrenaline overriding caution.

After another 20 minutes of difficult hiking, they reached a rocky outcrop, and there, partially hidden by overgrown brush and a snow drift, was the entrance to a cave.

The opening was narrow, barely wide enough for a person to squeeze through.

Deputy Cowwell knelt down and shined his light inside.

What he saw would haunt him for the rest of his life.

Sitting against the back wall of the cave, wrapped in a tattered emergency blanket, was Brenda Joyce.

Her eyes were open, staring straight ahead, unblinking.

She didn’t react to the light, didn’t turn toward the sound of his voice.

She just sat there, motionless, like a statue carved from stone.

Deputy Cowwell called out to her.

no response.

He carefully crawled into the cave, his heart pounding so hard he could hear it in his ears.

He reached out and touched her shoulder.

She was cold, but she was breathing.

Her pulse was weak, but steady.

She was alive, but when he looked into her eyes, he saw nothing.

No recognition, no fear, no relief, just emptiness.

He radioed for emergency medical services.

Within minutes, the other deputies were helping to carefully extract her from the cave.

She didn’t resist.

She didn’t help.

She simply allowed herself to be moved limp and silent.

The paramedics arrived within the hour, navigating the rough terrain with a stretcher and medical equipment.

When they reached Brenda, they immediately began assessing her condition.

She was severely dehydrated, malnourished, and hypothermic.

Her body temperature was dangerously low.

Her lips were cracked and bleeding.

Her skin pale and waxy.

But what disturbed them most was her complete lack of response.

She didn’t speak, didn’t blink, didn’t acknowledge their presence.

One paramedic, a woman named Rachel Ortis, had seen plenty of trauma cases in her career, but this was different.

Brenda’s eyes were open, but it was like no one was home.

Rachel tried talking to her, asking simple questions.

Nothing.

They loaded her onto the stretcher and began the slow, careful descent back to the vehicles.

Patricia and Robert Joyce were waiting at the trail head when the team emerged from the forest.

Patricia let out a cry and ran toward the stretcher.

But when she saw her daughter’s face, she stopped.

Brenda was alive, breathing, real, but she wasn’t there.

Patricia grabbed her hand, squeezed it, begged her to say something, anything.

Brenda stared past her, through her as if she were looking at something no one else could see.

Robert stood frozen, unable to process what he was witnessing.

The paramedics gently explained that Brenda needed immediate medical attention.

They transported her to Mercy Regional Medical Center in Durango, where a team of doctors was already preparing for her arrival.

News of her discovery spread like wildfire.

Within hours, every major news outlet in the country was covering the story.

A young woman missing for 60 days in the brutal Colorado winter found alive in a cave.

It should have been a miracle, but something about it felt deeply, unsettlingly wrong, and the questions everyone was asking had no answers.

At the hospital, doctors worked quickly to stabilize Brenda.

They administered introvenous fluids, warmed her body gradually to prevent shock, and ran a battery of tests.

Physically, aside from the dehydration and malnutrition, she was in surprisingly good condition.

No broken bones, no frostbite, no signs of major injury.

It didn’t make sense.

How had she survived for two months in subzero temperatures with minimal supplies? Her backpack found in the cave contained only a few energy bars, an empty water bottle, and a flashlight with dead batteries.

There was no fire pit, no evidence of shelter construction, no indication of how she’d managed to stay alive.

Dr.

Michael Brennan, the attending physician, was baffled.

He’d treated countless cases of hypothermia and exposure.

Victims who spent even a few days in those conditions usually suffered severe tissue damage.

But Brenda’s body showed almost none of that.

It was as if time had stopped for her inside that cave.

But the physical mystery pad in comparison to the psychological one.

Brenda remained completely unresponsive.

A neurologist.

Dr.

Vanessa Chang was brought in to assess her.

She performed cognitive tests, checked for brain injury, ran scans.

Everything came back normal.

There was no physical reason for Brenda’s silence.

Doctor Chang sat beside Brenda’s bed, speaking softly, trying to establish any form of connection.

She asked her to squeeze her hand, to blink, to nod.

Nothing.

Brenda’s eyes stayed fixed on some distant point, her expression blank.

It was as if she’d retreated somewhere deep inside herself, somewhere no one could reach.

Doctor Chang had seen catatonic states before, usually triggered by severe trauma.

But this felt different.

There was something deliberate about Brenda’s stillness, as if she were choosing not to come back.

The question haunting everyone was simple but terrifying.

What had she seen in that cave? Patricia and Robert stayed at the hospital day and night.

They took turns sitting beside Brenda’s bed, talking to her, playing her favorite music, showing her photos on their phones.

Anything to spark a reaction.

Patricia read aloud from books Brenda loved as a child.

She told stories about family vacations, inside jokes, moments they’d shared.

Her voice would crack, tears streaming down her face, but she kept going.

She refused to believe her daughter was truly gone.

Robert was quieter.

He held Brenda’s hand and watched her face, searching for any flicker of recognition.

Sometimes he’d lean close and whisper, “We’re here, sweetheart.

You’re safe now.

You can come back.

But Brenda never moved.

On the fourth day in the hospital, something changed.

It was subtle, almost imperceptible.

Patricia was reading a passage from a novel when Brenda’s fingers twitched.

Patricia stopped mid-sentence, her breath catching.

She stared at Brenda’s hand.

Did it move? She called for Robert, who’d stepped out to get coffee.

He rushed back into the room.

They both watched, holding their breath.

Brenda’s hand moved again, just slightly, curling inward.

Patricia gasped.

She pressed the call button for the nurse.

Within seconds, Dr.

Chang was in the room.

She leaned over Brenda, checking her vitals, her pupils.

Brenda, she said firmly.

Can you hear me? For the first time in days, Brenda blinked.

It was slow, deliberate.

Then her eyes shifted just a fraction toward the sound of Dr.

Cheng’s voice.

The room erupted in quiet relief.

It wasn’t much, but it was something.

Over the next few hours, Brenda began to show more signs of awareness.

Her eyes tracked movement.

She responded to touch, but she still didn’t speak.

Dr.

Chang explained that this was progress, that Brenda’s mind was slowly coming back online.

But recovery from this kind of trauma was unpredictable.

On day six, Brenda finally spoke.

It was just one word, barely a whisper, but it shattered the silence that had surrounded her.

Patricia was alone with her, brushing her hair gently, humming a lullaby she used to sing when Brenda was small.

And then so quietly, Patricia almost missed it, Brenda said.

Cold.

Patricia froze.

She leaned closer.

What did you say, honey? Brenda’s lips moved again.

So cold.

Tears poured down Patricia’s face.

She grabbed Brenda’s hand and squeezed it tight.

You’re safe now.

You’re warm.

You’re here with us.

Brenda’s eyes finally focused on her mother’s face.

And for the first time since she’d been found, there was something there.

Recognition, fear, and something else, something darker.

Patricia hit the call button, and within moments, the room was filled with doctors and nurses.

Brenda had spoken.

She was coming back.

But as Dr.

Chang would later note in her file, the look in Brenda’s eyes suggested that wherever she’d been, she hadn’t come back alone.

Over the following days, Brenda began to speak more, though her words were fragmented and often didn’t make sense.

She talked about the cold, about darkness, about being unable to move.

She mentioned hearing voices, though she couldn’t explain whose voices or what they said.

When asked what happened the day she went missing, she became agitated, her breathing rapid, her eyes darting around the room as if searching for an escape.

Dr.

R.

Chang advised the family to be patient, to let Brenda recover at her own pace.

Pushing her too hard could cause her to retreat again, but the authorities needed answers.

Deputy Cwell came to the hospital on day eight, hoping to get a statement.

He sat down beside Brenda’s bed, his notepad in hand, his voice gentle.

He explained that he just wanted to understand what happened to help piece together the mystery.

Brenda stared at him for a long moment.

Then she whispered, “I walk and then I was there.” Deputy Cowwell leaned forward.

“Where, Brenda? Where did you walk to?” She closed her eyes, her brow furrowing as if trying to remember.

The trees, the snow.

I kept walking.

I was lost.

Do you remember how you ended up in the cave? She nodded slowly.

I was tired.

So tired.

I needed to rest.

I saw the opening.

I went inside.

And then what? Her eyes opened.

And the look in them made Deputy Cowwell’s skin crawl.

I couldn’t leave.

Why not? Her voice dropped to a whisper.

Because it wouldn’t let me.

The room fell silent.

Deputy Cowwell glanced at Dr.

Chang, who stood near the door, her expression unreadable.

He turned back to Brenda.

What wouldn’t let you? Brenda didn’t answer.

She turned her face away, staring at the wall.

Deputy Cowwell tried asking more questions, but she’d shut down again.

It was clear she wasn’t ready to talk about whatever had happened inside that cave.

And honestly, Deputy Cowwell wasn’t sure he was ready to hear it.

The news of Brenda’s partial recovery brought a wave of relief and curiosity.

People wanted to know how she’d survived.

Experts weighed in on television, offering theories.

Some suggested she’d found a water source in the cave, perhaps melting snow or accessing an underground spring.

Others speculated that she’d entered a state of torper, a kind of human hibernation that slowed her metabolism and allowed her to conserve energy.

But none of those theories explained the physical evidence.

The cave had been thoroughly examined by investigators.

There was no water source, no food remnants, no sign of fire or warmth.

The temperature inside the cave had been measured at just above freezing, cold enough to kill someone within days, not sustain them for 2 months.

And then there was Brenda’s condition.

Despite the lack of food, her body hadn’t entered the severe stages of starvation.

Her muscle mass was depleted.

Yes, but not to the degree expected.

It was as if something had been sustaining her.

Melissa Harmon, Brenda’s roommate, visited her in the hospital on day 10.

She brought flowers and a card signed by dozens of people from their small town.

She sat beside the bed and held Brenda’s hand, tears streaming down her face.

“I’m so glad you’re okay,” she whispered.

Brenda looked at her.

Really looked at her.

And for a moment, Melissa saw the friend she’d known.

But then Brenda said something that made Melissa’s blood run cold.

I heard you calling for me.

Melissa’s eyes widened.

What? That first night I heard you.

You were calling my name.

Melissa shook her head.

Brenda, I wasn’t there.

I was here in town.

I called your phone, but I wasn’t in the mountains.

Brenda’s expression didn’t change.

I heard you, she repeated, her voice flat and certain.

Melissa didn’t know what to say.

She glanced at Patricia, who sat in the corner of the room, her face pale.

It was clear Brenda’s perception of reality had been severely distorted by whatever she’d endured.

As the days passed, more details emerged, though they only deepened the mystery.

Investigators interviewed Gregory Sutton, the man who’d first heard the sounds near his cabin.

He recounted the nights he’d lain awake.

Listening to what he now believed was Brenda’s voice carried on the wind.

But here’s what troubled the investigators, Gregory’s cabin was over 8 miles from the cave where Brenda was found.

The terrain between them was rugged and heavily forested, for sound to travel that distance, especially through trees and over ridges, was nearly impossible.

Yet Gregory insisted he’d heard it clearly night after night.

Deputy Cowwell walked the road himself from the cabin to the cave.

It took him nearly 4 hours of difficult hiking.

How had Brenda’s voice reached Gregory? And more disturbing, why had it stopped the moment she was found? It was as if the mountain itself had been calling for help on her behalf.

But that was impossible, wasn’t it? Dr.

Chang brought in a trauma specialist, Dr.

Leonard Hayes, to help with Brenda’s psychological recovery.

Doctor Hayes had decades of experience treating patients who’d survived extreme orals from natural disasters to captivity.

He sat down with Brenda on day 12, his approach calm and non-threatening.

He asked her simple questions, gave her space to answer or not answer.

Slowly, over several sessions, Brenda began to open up.

She described the first day how she’d been hiking the familiar trail when a sudden snowstorm rolled in.

She’d become disoriented, unable to see more than a few feet ahead.

She tried to retrace her steps, but got turned around.

Panic set in.

She wandered for hours, her hands numb, her legs weak.

When she saw the cave, it felt like a gift.

Shelter, safety.

She crawled inside exhausted and fell asleep.

When she woke up, everything had changed.

“Changed how?” Hayes asked gently.

Brenda stared at her hands, her fingers twisting together.

“It was darker, colder.

I tried to leave, but I couldn’t find the entrance.” “Couldn’t find it, but you just come in through it.” She shook her head.

“I know, but it wasn’t there.

I felt along the walls crawling on my hands and knees.

There was no opening, just rock.

Doctor Hayes frowned.

You’re saying the entrance disappeared? I don’t know.

Maybe I was confused.

Maybe I was in shock.

But I swear I couldn’t find it.

I kept searching, kept calling for help, but no one came.

And then I stopped trying.

Why did you stop? Her voice became distant, hollow.

because I realized it didn’t matter.

I wasn’t getting out.

Doctor Hayes made a note.

It was possible that hypothermia and fear had caused hallucinations, spatial disorientation.

But the way Brenda spoke, the certainty in her voice suggested she truly believed what she was saying.

And that raised a troubling question.

What had really happened inside that cave? By day 15, Brenda was physically strong enough to be discharged.

The doctors recommended continued psychiatric care and close monitoring, but there was no medical reason to keep her hospitalized.

Patricia and Robert took her home to their house in Denver, hoping familiar surroundings would help her heal.

But Brenda wasn’t the same person who’d left for that hike.

She was quiet, withdrawn, and spent most of her time staring out the window.

She ate little and slept less.

At night, Patricia could hear her daughter pacing the hallway, her footsteps soft but restless.

One evening, Patricia found Brenda standing in the backyard, barefoot in the snow, staring up at the mountains in the distance.

Brenda, honey, come inside.

You’ll freeze.

Brenda didn’t move.

Do you hear it? Patricia listened.

All she heard was the wind.

Hear what? Brenda’s voice was barely audible.

It’s calling.

Patricia felt a chill that had nothing to do with the cold.

She gently guided Brenda back inside, her heart heavy with worry.

Meanwhile, back in Silverton, Deputy Cwell couldn’t let the case go.

Something about it gnawed at him, kept him awake at night.

He returned to the cave multiple times, examining every inch of it with a team of forensic specialists.

They documented everything, took soil samples, measured dimensions, and photographed the interior.

The cave was small, roughly 10 ft deep and 6 ft wide.

The walls were solid limestone, ancient and unyielding.

There was only one entrance, the same narrow opening through which they’d found Brenda.

There was no other way in or out.

No hidden passages, no collapsed sections, just one entrance, which meant Brenda’s claim about not being able to find it made no sense.

Unless she’d been so disoriented that she’d simply missed it in the dark.

Deputy Cowwell tried to convince himself that was the answer, but it didn’t explain everything else.

It didn’t explain how she’d survived.

It didn’t explain the sounds Gregory had heard, and it didn’t explain the look in her eyes when they’d first found her.

On day 20, a local news reporter named Amanda Reeves requested an interview with Brenda.

Patricia initially refused, wanting to protect her daughter from the media frenzy, but Brenda surprised everyone by agreeing.

She said she wanted to tell her story that maybe it would help her make sense of it.

The interview was conducted in the Joyce family living room with Patricia and Robert present.

Amanda kept her questions gentle, letting Brenda speak at her own pace.

Brenda described the hike, the storm, the cave.

She talked about the cold and the fear, but then she said something that made Amanda pause.

I wasn’t alone in there.

Amanda leaned forward.

What do you mean? Brenda’s eyes were distant, unfocused.

There was something else.

I couldn’t see it, but I could feel it watching me.

Waiting.

Waiting for what? Brenda’s voice dropped to a whisper for me to give up.

The room fell silent.

Patricia reached for her daughter’s hand, but Brenda pulled away.

She stood abruptly and walked out of the room, leaving everyone stunned.

The interview aired 2 days later, and the response was immediate.

Some viewers expressed sympathy, believing Brenda had experienced trauma induced hallucinations.

Others were more skeptical, suggesting she’d fabricated parts of her story for attention.

But a small group of people, mostly locals who knew the mountains well, took her claims seriously.

They reached out with their own stories.

Stories of strange occurrences in the San Juan range.

Hikers who’d felt watched.

Campers who’d heard voices in the night.

A man named Trevor Walsh called the sheriff’s office.

insisting he’d had a similar experience 5 years earlier.

He’d gotten lost on a trail and taken shelter in a cave.

He’d felt an overwhelming sense of dread, as if something invisible were pressing down on him.

He’d forced himself to leave, barely making it out before collapsing from exhaustion.

Deputy Cowwell listened to Trevor’s account, his skepticism waring with something deeper.

What if there was more to this than simple survival? What if the mountain itself held secrets no one wanted to acknowledge? Dr.

Hayes continued working with Brenda, conducting weekly sessions at the Joyce home.

He employed techniques designed to help her process trauma, including guided visualization and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Brenda cooperated, but progress was slow.

She struggled to articulate what she’d experienced, often retreating into silence when the memories became too vivid.

During one session, Dr.

Hayes asked her to describe the moment.

She realized she might not survive.

Brenda closed her eyes, her breathing shallow.

I stopped counting the days.

Time didn’t feel real anymore.

I was just there existing.

I thought about my family.

about Melissa, about everything I’d never get to do.

And I felt so angry.

Not at the mountain or the storm, at myself for giving up.

Did you give up? Dr.

Hayes asked gently.

She opened her eyes and they were filled with tears.

“I think I did.

I think I died in there.” And then something brought me back.

That statement haunted Dr.

Hayes.

He’d treated hundreds of patients, heard countless descriptions of near-death experiences, but this felt different.

Brenda wasn’t talking about seeing a light or feeling peace.

She was talking about something else, something she couldn’t name.

He consulted with colleagues, reviewed literature on extreme survival and psychological trauma.

Nothing quite matched what Brenda was describing.

Meanwhile, Brenda’s behavior at home grew more erratic.

She started refusing to sleep in her bedroom.

Instead, curling up on the couch in the living room with all the lights on.

Patricia would find her in the middle of the night, staring at the ceiling, her eyes wide and unblinking.

When asked what was wrong, Brenda would only say, “It’s too quiet.” Patricia didn’t understand.

too quiet.

The house was silent, peaceful.

But for Brenda, the silence was unbearable.

It reminded her of the cave, of the darkness, of the things she’d felt but never seen.

3 weeks after her rescue, Brenda received an unexpected visitor.

A woman named Clare Donovan, a professor of anthropology from Colorado State University, reached out to the family.

She’d seen the news coverage and wanted to speak with Brenda about her experience.

Clare had spent years studying indigenous folklore and oral histories of the Sanjon Juan Mountains.

She believed there was more to the land than geology and wildlife.

Patricia was hesitant, but Brenda agreed to the meeting.

Clare arrived with a notebook filled with handwritten notes and old photographs.

She sat across from Brenda and spoke with quiet intensity.

The Ute people who lived in these mountains for thousands of years have stories about places like the one you found.

Clare began.

They called them spirit traps.

Caves or valleys where the boundary between our world and something else is thin.

Brenda listened, her expression unreadable.

What kind of something else? Clare hesitated.

They believed certain places hold energy consciousness.

Not good or evil necessarily, just other.

Clare explained that according to Ute tradition, these places could sustain a person in ways that defied logic, but at a cost.

Those who entered spirit traps often emerged changed, marked by the experience.

Some never spoke again.

Others spoke only in riddles.

A few claimed they’d been given visions, glimpses of things beyond human understanding.

Brenda leaned forward.

Did anyone ever survive like I did.

Clare nodded slowly.

There are stories, but they’re rare, and the people who survived were never quite the same.

Patricia interrupted, her voice sharp.

Are you saying my daughter was in some kind of supernatural place? That’s ridiculous.

Claire didn’t flinch.

I’m saying that people have experienced things in these mountains that science can’t explain.

Whether you call it supernatural or something else is up to you.

But Brenda’s survival, the way she was found, the condition she was in, it matches the old stories.

Brenda’s voice was quiet but firm.

I believe her.

Patricia stared at her daughter, a chill running down her spine.

After Clare left, Patricia confronted Brenda.

You can’t seriously believe what she said.

Spirit traps.

That’s folklore, honey, not reality.

Brenda looked at her mother, and for the first time since coming home, there was clarity in her eyes.

Then how do you explain it, Mom? How did I survive? Why couldn’t I find the way out? Why did it feel like something was keeping me there? Patricia had no answers.

She wanted to believe there was a rational explanation, something grounded in science.

But deep down, she couldn’t shake the feeling that her daughter had experienced something beyond ordinary comprehension.

That night, Robert sat down with Brenda in the living room.

He’d been quiet throughout everything, processing in his own way.

“Do you want to go back?” he asked.

Brenda blinked.

“What?” “To the cave.” “To see it again.

Maybe it would help you make sense of things.” Brenda shook her head vehemently.

“No, I can’t.

I won’t.” Robert nodded.

He didn’t push, but he saw the fear in her eyes raw and real.

Whatever had happened in that cave, it had left scars deeper than anyone could see.

As winter gave way to early spring, Brenda slowly began to reclaim pieces of her life.

She started attending a support group for trauma survivors where she met others who’d faced their own orals.

Hearing their stories, their struggles and triumphs helped her feel less alone.

She also began journaling, writing down fragments of memories that surfaced in dreams or quiet moments.

Dr.

Hayes encouraged this, believing it would help her process the experience.

But one entry dated March 7th stood out.

In it, Brenda wrote, “I remember now.” The voice I heard wasn’t calling for help.

It was calling me.

It knew my name.

It said, “Stay.

You belong here.” And for a moment, I almost believed it.

Dr.

Hayes read the entry during their next session, his expression troubled.

Do you still feel that pull like something is calling you? Brenda hesitated.

Then she nodded.

Every night I dream about the cave.

And in the dream, I walk back inside and I don’t come out.

Deputy Cwell, meanwhile, had quietly continued his investigation.

He’d interviewed everyone connected to the case, reviewed every piece of evidence, and even consulted with experts in survival psychology and environmental science, but nothing added up.

On a hunch, he reached out to the National Park Service to see if there were any other reports of unusual incidents in the San Juan Range.

What he discovered sent a chill down his spine over the past 30 years.

There had been 11 cases of hikers going missing in the area surrounding the cave where Brenda was found.

Of those 11, only three had been recovered.

Two were found deceased, victims of exposure.

The third was a man named Owen Harris, who’d gone missing for 26 days in 1998.

He’d been found alive sitting in a cave, staring at the wall, just like Brenda.

Deputy Cowell tracked down Owen’s family.

His sister, Linda Harris, agreed to speak with him over the phone.

Linda explained that Owen had been an experienced outdoorsman, a guide who knew the mountains intimately.

His disappearance had shocked everyone.

When he was found, he was severely malnourished, but otherwise unharmed.

He never spoke about what happened.

In fact, he barely spoke at all after that.

He withdrew from his family, quit his job, and eventually moved to a remote cabin in Montana.

Linda had tried to reach out over the years, but Owen never responded.

“He was different,” Linda said, her voice heavy with sadness.

“It was like part of him never left that cave.” Deputy Cowwell asked if Owen had ever mentioned anything unusual about the experience.

Linda paused.

Once he said he’d made a choice.

He wouldn’t explain what he meant, but he said he’d chosen to come back and he regretted it.

Deputy Cwell thanked her and ended the call, his mind racing.

A choice.

What kind of choice? And what did it mean that Brenda had survived when so many others hadn’t? Armed with this new information, Deputy Cowwell reached out to Clare Donovan, the anthropologist who’d visited Brenda.

They met at a coffee shop in Durango, where Clare shared more of her research.

She showed him maps marked with locations of reported disappearances, all clustered within a 15mi radius.

She explained that indigenous oral histories described this area as sacred but dangerous, a place where the spirit world and the physical world over overlapped.

They believed that certain places demand something from those who enter.

Clare said, a test or a sacrifice.

Not everyone passes.

Deputy Cowwell leaned back, running a hand through his hair.

So what are you saying? that the mountain is conscious, that it chooses who lives and who dies.

Clare shook her head.

I’m saying that there are forces in this world we don’t understand.

Call it energy, call it consciousness, call it something else entirely, but ignoring it doesn’t make it less real.

Deputy Cowwell wanted to dismiss it.

Everything in his training told him to look for logical explanations, but the pattern was undeniable.

The cave, the survivors, the way they all emerged changed.

Something was happening in those mountains.

Something beyond his ability to explain or control.

In late March, Brenda made a decision that surprised everyone.

She announced that she wanted to return to Silverton to face the place where it all happened.

not to go back into the cave, but to see the mountains again, to stand at the trail head where her truck had been parked.

Patricia was against it, fearing it would trigger a relapse.

But Dr.

Hayes thought it might be therapeutic, a way for Brenda to reclaim her sense of agency.

Robert offered to drive her.

They made the trip on a clear Saturday morning.

the roads winding through valleys still dusted with snow.

Brenda was quiet during the drive, her eyes fixed on the passing landscape.

When they reached the trail head, she got out of the car and stood in the parking lot, breathing in the cold mountain air.

The peaks rose around her, ancient and imposing.

She felt their weight, their presence, but she didn’t feel fear.

She felt something else.

acceptance.

Robert stayed by the car, giving her space.

Brenda walked to the edge of the lot where the trail began.

She didn’t go far, just stood there, looking up at the path that had led to so much pain and mystery.

She thought about the woman she’d been before, the one who’d walked this trail without fear, who’d loved the wilderness and trusted it.

That woman was gone.

In her place was someone who understood that the world held shadows, places where logic ended and something older began.

She closed her eyes and whispered, “Thank you.” She didn’t know if she was thanking the mountain for letting her go or apologizing for taking something.

She shouldn’t have, maybe both.

When she opened her eyes, she felt lighter, as if a weight she’d carried since the cave had finally lifted.

She turned and walked back to her father.

“I’m ready to go home.” Robert nodded, relief washing over him.

They drove back to Denver in comfortable silence.

Over the following weeks, Brenda’s nightmares began to fade.

She still thought about the cave, still felt the pull of something she couldn’t name, but it no longer consumed her.

She started reconnecting with friends, slowly rebuilding the life she’d lost.

Melissa visited often, and they spent hours talking, laughing, remembering who they’d been before everything changed.

Brenda even returned to substitute teaching, though she chose elementary schools, finding comfort in the innocence and energy of young children.

They didn’t know her story, didn’t look at her with pity or curiosity.

They just saw Miss Joyce, the teacher who read funny voices and always had stickers.

It was exactly what she needed.

But there were still moments when the past crept in.

When she’d be driving and see mountains in the distance and feel her chest tighten.

When she’d wake in the middle of the night, certain she’d heard something calling her name.

In those moments, she’d remind herself that she’d survived, that she’d chosen to come back, and that choice mattered.

In May, Deputy Cowwell received a call from the park service.

They were considering closing public access to the area around the cave, citing safety concerns, too many disappearances, too many unanswered questions.

Deputy Cowwell supported the decision, though he knew it wouldn’t stop everyone.

There would always be people drawn to the mystery, to the danger, but maybe it would save a few lives.

He thought about Brenda, about Owen Harris, about all the others who’d entered those mountains and never returned.

He thought about the line between the known and the unknown, and how thin it really was.

Before the closure took effect, Deputy Cowwell made one final trip to the cave.

He stood at the entrance, shining his flashlight into the darkness.

He didn’t go inside.

He just wanted to see it one more time, to understand what had drawn so many people into its depths.

But standing there, he felt it, too.

The pull, the sense that something waited inside, patient and eternal.

He backed away slowly, his heart pounding.

Whatever was in that cave, it was still there, still waiting.

He turned and hiked back to his vehicle, feeling eyes on his back the entire way.

When he reached his truck, he looked back one more time.

The cave entrance was barely visible, hidden by shadow and stone.

He made a mental note to recommend additional segage, warnings to keep people away, but he knew deep down that warnings wouldn’t be enough.

Some people would still go looking.

Some people would still be called.

That night, Deputy Cwell went home and wrote a detailed report documenting everything he’d learned.

He included eyewitness accounts, historical records, and his own observations.

He submitted it to his superiors, knowing it would likely be filed away and forgotten.

But he’d done his duty.

He’d told the truth even if no one wanted to hear it.

And he hoped more than anything that Brenda Joyce would find peace, that she’d be able to move forward to build a life untouched by the darkness she’d endured.

By summer, Brenda had made significant progress.

She’d moved back into her own apartment, the one she’d shared with Melissa, before the disappearance.

It felt like reclaiming territory, taking back her independence.

She decorated the space with photos and plants, filling it with life and color.

She even adopted a rescue dog, a small terrier mix named Scout, who followed her everywhere.

Scout seemed to sense when Brenda was struggling, curling up beside her during difficult moments.

Doctor Hayes reduced their sessions to once a month, noting that Brenda had developed healthy coping mechanisms.

She exercised regularly, maintained a journal, and stayed connected to her support network.

She’d also started volunteering with a search and rescue organization, using her experience to help train others in wilderness safety.

It was her way of giving back, of transforming her trauma into something meaningful.

But there was one thing she couldn’t shake.

The dreams, they’d lessened in frequency, but not intensity.

In them, she always returned to the cave.

And in the cave, she always heard the voice.

One night in late July, Brenda woke from such a dream, her heart racing.

Scout was whining at the foot of the bed.

Sensing her distress, she got up, poured herself water, and stood by the window.

The city lights stretched before her.

Thousands of lives going about their business, unaware of the mysteries that lurked in wild places.

She thought about Owen Harris, the man Deputy Cowwell had told her about, the one who’d survived but never truly came back.

She wondered if he still heard the voice too, if he still felt the pull.

She considered trying to find him, to talk to someone who might understand.

But something stopped her.

Maybe some experiences were meant to be carried alone.

Maybe sharing them would only give them more power.

She returned to bed, scout curling against her side.

She closed her eyes and whispered the same words she whispered every night.

I chose to come back.

I chose life.

And slowly the darkness receded and she slept.

In August, Amanda Reeves, the reporter who’d interviewed Brenda, reached out again.

She’d been following the story, tracking the closure of the trail and the ongoing investigation.

She wanted to do a follow-up piece focusing on Brenda’s recovery and resilience.

Brenda agreed, but this time on her terms.

They met at a park sitting on a bench overlooking a lake.

Amanda asked how she was doing, and Brenda answered honestly.

She talked about the progress she’d made, the challenges she still faced.

She talked about the importance of mental health support and the need for better wilderness safety education.

But when Amanda asked if she’d ever go hiking again, Brenda hesitated.

I don’t know, she admitted.

Part of me wants to part of me needs to prove that I’m not afraid, but another part knows that some places aren’t meant for everyone, and that’s okay.

Amanda nodded, respecting her honesty.

The resulting article was compassionate and thoughtful, focusing on Brenda’s strength rather than the sensational aspects of her story.

That fall, Brenda received a letter.

It had no return address, just a postmark from Montana.

Inside was a single handwritten page.

Dear Brenda, my name is Owen Harris.

I read about you in the news.

I know what you went through because I went through it, too.

I want you to know that it gets easier.

The voice fades, the pull weakens, but it never completely goes away.

You’ll always be connected to that place and it to you.

That’s the price of survival.

But it’s a price worth paying.

You chose to come back.

That means you’re stronger than the darkness.

Don’t ever forget that.

Stay in the light, Owen.

Brenda read the letter three times, tears streaming down her face.

She’d never felt so understood, so validated.

She folded the letter carefully and placed it in a box with other meaningful items.

She didn’t try to write back.

She didn’t need to.

The message had been enough.

She wasn’t alone, and she wasn’t broken.

She was a survivor.

Winter returned to Colorado, blanketing the mountains in snow once again.

Brenda watched from her apartment window as the first flakes fell.

Feeling a familiar tightness in her chest, but this time it passed quickly, she bundled up, clipped Scout’s leash, and went for a walk.

The cold air filled her lungs, sharp and clean.

She thought about the year that had passed, about everything she’d lost and everything she’d gained.

She thought about the cave, dark and silent beneath the snow, and she thought about the choice she’d made, to come back, to live, to fight.

As she walked through the quiet streets, scout trotting happily beside her, she realized something important.

The cave hadn’t taken anything from her.

It had revealed something.

Her strength, her will to survive, her refusal to be consumed by darkness.

and that was a gift, however painful.

She returned home, made tea, and sat by the window.

The city glowed below, and the mountains rose in the distance, ancient and unknowable.

By the time the anniversary of her disappearance arrived in January, Brenda had decided to do something she’d never thought possible.

She agreed to speak at a wilderness survival conference, sharing her story with search and rescue professionals, park rangers, and outdoor enthusiasts.

Patricia was nervous, worried it would be too much.

But Brenda felt ready.

She stood before a room of a hundred people and told them what happened.

She talked about the storm, the cave, the darkness.

She talked about the disorientation, the fear, the moment she thought she’d never leave.

But she also talked about the will to survive, the small decisions that kept her alive, the choice to rest when needed, to conserve energy, to hold on to hope even when it seemed impossible.

She didn’t mention the voice or the feeling of being watched.

Those details were hers to keep.

When she finished, the room erupted in applause.

People approached her afterward, thanking her, telling their own stories of survival and loss.

She listened to each one, offering comfort and understanding.

One woman, a retired park ranger named Susan Caldwell, pulled Brenda aside.

“I worked in the San Juans for 20 years,” Susan said quietly.

“I know the area where you were found.

I’ve heard the stories and I believe you experienced something real, something that can’t be explained away.

Brenda felt a wave of relief.

Thank you, she whispered.

Susan squeezed her hand.

You’re not crazy.

You’re not broken.

You’re just one of the few who’ve seen behind the curtain.

And that’s a heavy thing to carry, but you’re carrying it well.

Those words stayed with Brenda long after the conference ended.

She realized that part of healing was accepting that she’d never have all the answers, that some mysteries were meant to remain unsolved and that was okay.

She didn’t need to understand what happened in the cave to move forward.

She just needed to accept that it happened and that she’d survived, and that was enough.

As spring approached once more, Brenda found herself at a crossroads.

She’d been offered a full-time teaching position at an elementary school.

It was stable, safe, predictable, everything she thought she wanted.

But another opportunity had also presented itself.

A wilderness therapy organization that worked with at risk youth was looking for guides who understood trauma and resilience.

They wanted people who could lead kids into nature and teach them that they were stronger than they believed.

The job would mean returning to the mountains, facing her fears head on.

It would mean risking the nightmares, the memories, the pull of that dark place.

But it would also mean transforming her pain into purpose.

Brenda sat with the decision for weeks, talking it through with Dr.

Hayes with her parents with Melissa.

In the end, the choice was clear.

She accepted the wilderness therapy position because she’d learned something in that cave, something crucial.

Fear would always exist, but it didn’t have to control her.

On her first day leading a group of teenagers into the foothills, Brenda felt her hands shake as she checked their gear.

She looked up at the mountains rising before them, felt the familiar tightness in her chest.

But then she looked at the kids, saw their nervous excitement, their need for someone to believe in them, and she knew she was exactly where she needed to be.

They hiked for hours, Brenda pointing out landmarks, teaching them how to read the terrain, how to stay safe.

When they set up camp that evening and gathered around the fire, one of the girls asked Miss Joyce, “Have you ever been scared out here?” Brenda smiled, the fire light dancing across her face.

“Yes,” she said honestly.

“I’ve been terrified.

But I learned that being scared doesn’t make you weak.

It makes you human.

And what you do with that fear is what defines you.” The kids listened intently as she shared pieces of her story, carefully edited but still true.

When she finished, they asked questions, shared their own fears.

And in that moment, sitting under the stars with these broken, beautiful young people, Brenda felt something she hadn’t felt in a long time.

Peace.

Years would pass.

Brenda would lead hundreds of kids into the wilderness, helping them discover their own strength.

She’d eventually write a book about survival, not just physical, but emotional and spiritual.

She’d fall in love with a fellow guide named Marcus, who understood her silences and never pushed her to explain.

They’d build a life together, one grounded in nature and filled with purpose.

But on quiet nights, when the wind howled through the mountains, Brenda would sometimes stand at her window and listen, and she’d hear it, faint, distant, the voice that had called her name in the darkness, the voice that had offered her a choice.

She never told anyone about those moments.

She didn’t need to because she’d made her choice.

She’d chosen to come back, to live, to fight.

And no matter how many times the darkness called, her answer would always be the same.

Not today, not ever.

The cave still stands in the Sanan Mountains, hidden beneath snow and stone, closed to the public, but never truly empty, waiting, watching, calling.

But Brenda Joyce walks in the light now.

And she has no intention of going back.

Some mysteries aren’t meant to be solved.

They’re meant to be survived.

And the question that lingers isn’t what happened in that cave.

It’s what Brenda refused to become because of

News

The men Disappeared In The Appalachian Forests.Two Months Later, Tourists Found Them Near A Tree

In September of 2016, two 19-year-old students with no survival experience disappeared into the Appalachian forests after wandering off a…

The men Disappeared In The Appalachian Forests.Two Months Later, Tourists Found Them Near A Tree

In September of 2016, two 19-year-old students with no survival experience disappeared into the Appalachian forests after wandering off a…

She Disappeared On The Appalachian Trail.Four Months Later A Discovery In A Lake Changed Everything

In April 2019, 19-year-old student Daphne Butler set off on a solo hike along the Appalachian Trail in the Cherokee…

Three Teenagers Went Missing In Arizona.Nine Months Later, One Emerged From The Woods

Three Teenagers Went Missing In Arizona. Nine Months Later, One Emerged From The Woods On March 14th, 2018, three teenagers…

Three Teenagers Went Missing In Arizona.Nine Months Later, One Emerged From The Woods

On March 14th, 2018, three teenagers got off a bus at an inconspicuous stop in the pine forests of Arizona….

She disappeared in the forests of Mount Hood — two years later, she was found in an abandoned bunker

In September 2020, a group of underground explorers wandered into a remote ravine on the northern slope of Mount Hood…

End of content

No more pages to load