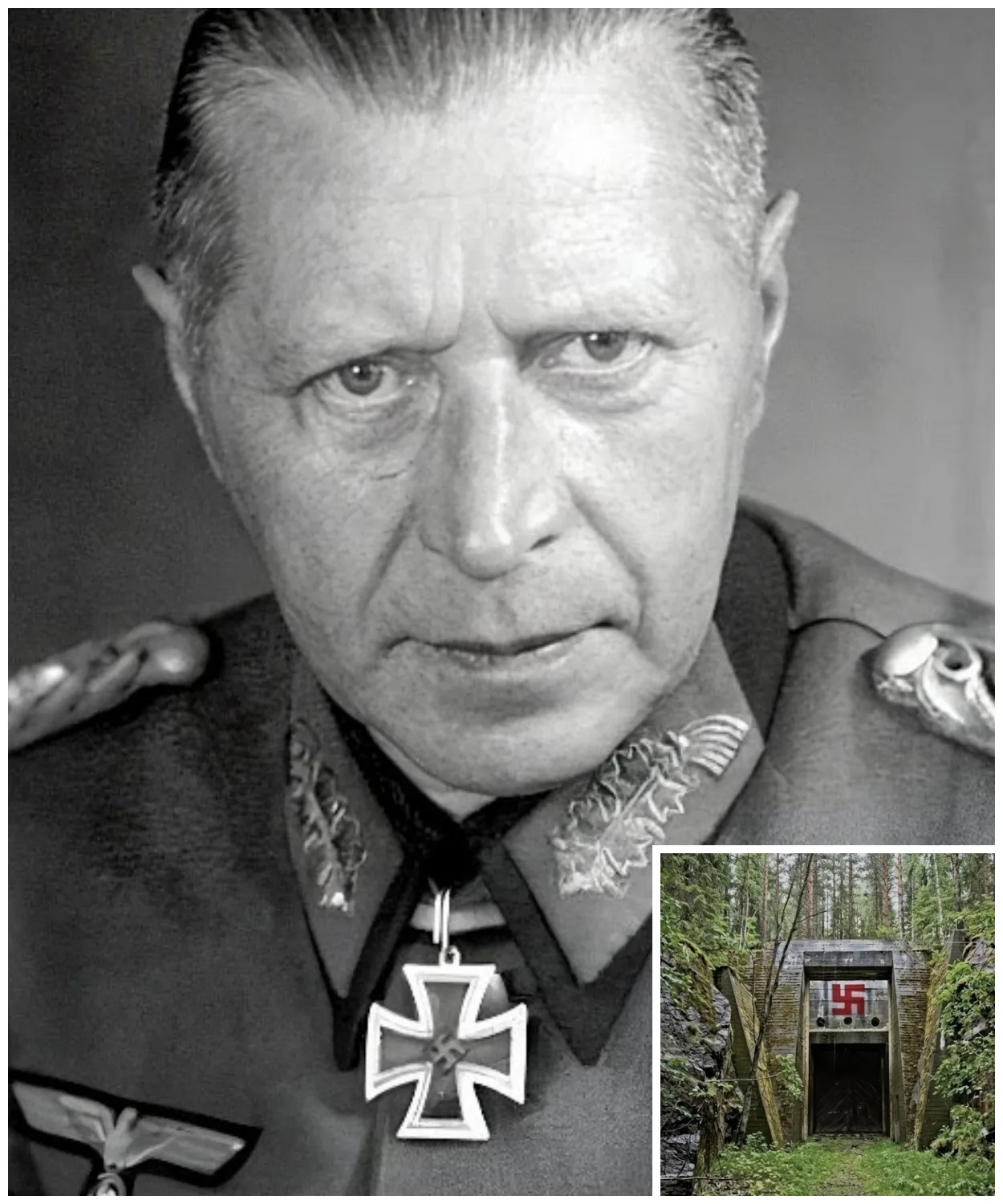

In the spring of 1,945 as Allied forces closed in on Berlin, a highranking German general made a decision that would baffle historians for the next eight decades.

He didn’t surrender.

He didn’t flee to South America like so many of his colleagues.

He simply vanished without a trace, taking with him military secrets that could have changed our understanding of the final days of World War II.

For 80 years, his disappearance remained one of history’s most perplexing mysteries.

That is until a routine wildlife survey in the Bavarian forest led to a discovery so extraordinary that it would rewrite everything we thought we knew about the war’s end.

What that survey team found hidden beneath decades of forest growth wasn’t just a bunker.

It was a time capsule containing documents, maps, and evidence of a secret operation so classified that even today, government officials are reluctant to discuss its full implications.

German General Vanished in 1945 — 80 Years Later His Hidden Forest Bunker Was Discovered by Accident

In the spring of 1,945 as Allied forces closed in on Berlin, a highranking German general made a decision that would baffle historians for the next eight decades.

He didn’t surrender.

He didn’t flee to South America like so many of his colleagues.

He simply vanished without a trace, taking with him military secrets that could have changed our understanding of the final days of World War II.

For 80 years, his disappearance remained one of history’s most perplexing mysteries.

That is until a routine wildlife survey in the Bavarian forest led to a discovery so extraordinary that it would rewrite everything we thought we knew about the war’s end.

What that survey team found hidden beneath decades of forest growth wasn’t just a bunker.

It was a time capsule containing documents, maps, and evidence of a secret operation so classified that even today, government officials are reluctant to discuss its full implications.

The story you’re about to hear involves coded messages, underground networks, and a conspiracy that reaches into the highest levels of wartime command.

But most shocking of all, the general’s final recorded words suggest he knew something about the war’s outcome that no one else did.

Something that made him believe disappearing was his only option.

October 15th, 1,944.

General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steinberg stood at the window of his command post in the Bavarian Alps, watching snow fall on the mountains he’d called home for most of his military career.

At 52 years old, he was one of Germany’s most decorated officers, a brilliant tactician who had earned respect even from his enemies.

His strategic mind had helped plan some of the Vermach’s most successful early campaigns.

But now, as autumn turned to winter, even von Steinberg could see the writing on the wall.

The general wasn’t your typical Nazi officer.

Born into a Prussian military family, he’d joined the army long before Hitler’s rise to power.

His loyalty was to Germany, not to the party, a distinction that would prove crucial in the months to come.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Fon Steinberg kept detailed personal journals documenting not just military operations, but his growing concerns about the direction of the war and the regime he served.

Those journals discovered decades later reveal a man increasingly troubled by what he witnessed.

Entry after entry describes his horror at reports filtering back from the Eastern Front, his disgust with SS operations and his growing belief that Germany’s leadership had lost all connection to reality.

But Von Steinberg was also a pragmatist.

He understood that speaking out meant certain death.

So he kept his thoughts private while continuing to serve with distinction.

By early 1945, von Steinberg had been reassigned to oversee defensive preparations in the Bavarian forest region.

Officially, his mission was to coordinate with local commanders to prepare for the inevitable Allied advance.

Unofficially, he was beginning to plan something far more complex.

Intelligence reports from that period show increased radio traffic in his sector, coded transmissions that didn’t match any known German military protocols.

Something was happening in those mountains, something that wouldn’t appear in any official war records.

The first clue that von Steinberg was planning his disappearance came from his aid to camp, Lieutenant Klaus Hoffman.

Years later, Hoffman would tell Allied interrogators about the general’s increasingly secretive behavior in the final weeks of the war.

Private meetings with unknown civilians, trips into the forest that lasted for days, and most puzzling of all, requisitions for construction materials that seemed to have no military purpose.

Hoffman described finding his commander one morning in March 1945 hunched over topographical maps of the local area.

The maps were covered in markings, elevation calculations, and what appeared to be architectural sketches.

When Hoffman asked about them, Von Steinberg simply smiled and said he was preparing for the future.

At the time, the lieutenant assumed his general was planning defensive positions.

He had no idea he was witnessing the birth of one of history’s most elaborate disappearances.

The construction project began in secret sometime in February 1945.

Using a carefully selected crew of engineers and laborers, von Steinberg oversaw the excavation of what would become his hidden bunker.

The location was perfect, a remote valley deep in the Bavarian forest, accessible only by a network of hunting trails that few people knew existed.

The site was hidden by dense tree cover and positioned in such a way that it would be invisible to aerial reconnaissance.

But this wasn’t just any bunker.

The facility Von Steinberg had constructed was a marvel of engineering.

Designed not for temporary shelter, but for long-term survival.

The main chamber was reinforced with steel and concrete, equipped with its own ventilation system, water supply, and enough storage space for months of provisions.

Adjacent rooms housed a communication center, a library, and what appeared to be a workshop equipped with precision instruments.

The most intriguing aspect of the bunker was its communication capabilities.

Allied intelligence would later discover that von Steinberg had somehow acquired radio equipment far more advanced than standard military issue.

The transmitter was capable of reaching locations across Europe and beyond, suggesting that the general’s plans extended far beyond simply hiding from the advancing allies.

Construction was completed in record time with the final touches added in early April 1945.

By then, American forces were already crossing the Rine, and Soviet troops were approaching Berlin.

Germany’s defeat was no longer a question of if, but when.

Yet, Von Steinberg seemed oddly calm about the situation, as if he knew something others didn’t.

The general’s behavior in those final weeks became increasingly erratic.

He began dismissing staff, sending loyal officers away on fabricated missions, and systematically reducing the number of people who knew his whereabouts.

Those who remained described a man who seemed to be preparing for a journey, though none could say where he might be going.

Lieutenant Hoffman’s final conversation with his commander took place on April 20th, 1,945, Hitler’s birthday.

The irony wasn’t lost on Von Steinberg, who had grown to despise the man whose orders he’d been following for years.

The general handed Hoffman a sealed envelope with instructions not to open it until May 1st.

Inside was a letter that would later become one of the key pieces of evidence in understanding Von Steinberg’s disappearance.

The letter was brief but cryptic.

Von Steinberg wrote that he could no longer serve a cause he didn’t believe in, but neither could he surrender to forces that might use him for propaganda purposes.

He spoke of a third option, a path that would allow him to serve his true country while avoiding the fate that awaited so many of his colleagues.

The letter ended with a promise that someday when the time was right, the truth would be revealed.

On the morning of April 25th, 1,945, General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steinberg left his command post for what would be the last time.

He told his remaining staff that he was conducting a final inspection of defensive positions and would return by evening.

He never did.

When search parties were sent out the following day, they found no trace of the general or the vehicle he’d been driving.

The official report filed by German command stated that General von Steinberg was missing in action, presumed killed in combat with advancing Allied forces.

No body was ever found, no witnesses came forward, and no evidence of his fate was discovered.

As far as the military bureaucracy was concerned, he had simply vanished into the chaos of Germany’s final defeat.

But von Steinberg hadn’t vanished at all.

He had simply activated the most carefully planned disappearance in military history.

While Allied and German forces battled across the German countryside, the general was settling into his hidden bunker, beginning a secret existence that would last for years.

He had enough supplies to survive for months.

And more importantly, he had a plan for what would come next.

The bunker’s communication equipment allowed von Steinberg to monitor the war’s progress from his hidden refuge.

He listened as Berlin fell, as Hitler died in his own bunker, and as Germany formally surrendered.

But instead of emerging to face whatever justice awaited former Vermacht officers, the general remained hidden, waiting for reasons that wouldn’t become clear for decades.

Allied intelligence services eventually became aware of Von Steinberg’s disappearance.

But with thousands of German military personnel unaccounted for in the war’s aftermath, one missing general wasn’t a high priority.

Some investigators theorized that he’d fled to South America like other Nazi officials.

Others assumed he’d been killed in the final battles and his body never recovered.

None suspected that he was living just miles from where he’d last been seen, hidden beneath the forest floor.

The search for Von Steinberg continued sporadically throughout the late 100, 940 seconds, and early 1,950 seconds.

Nazi hunters followed leads across Europe and South America, always one step behind a ghost that had never actually left Germany.

Intelligence files from the period show that various agencies investigated reported sightings in Argentina, Paraguay, and even the United States.

But none of these leads proved credible.

Meanwhile, deep in the Bavarian forest, Von Steinberg was adapting to his new existence.

The bunker’s ventilation system allowed him to remain underground for extended periods, while carefully planned supply runs under cover of darkness kept him fed and informed about the changing world above.

He had become a hermit by choice, a man who had erased himself from history while remaining very much alive.

The general’s journals from this period, later discovered in the bunker, reveal a complex psychological transformation.

The military officer who had once commanded thousands of men was learning to live in complete solitude sustained only by his conviction that he had chosen the right path.

He wrote extensively about his reasons for disappearing, his hopes for Germany’s future, and his growing belief that he was preserving something important for future generations.

By 1950, most official searches for von Steinberg had been called off.

The world had moved on to new conflicts and new concerns, and the missing general had become just another unsolved mystery from the war.

His name appeared occasionally in books about Nazi fugitives, but without new evidence, there was little to distinguish his case from hundreds of others.

What no one realized was that Fon Steinberg’s disappearance was only the beginning of his story.

The bunker he’d constructed was designed for more than simple survival.

It was a repository, a hidden archive containing documents and artifacts that would prove invaluable to future historians.

The general had spent his final months of official service gathering evidence, copying documents, and preserving records that others were eager to destroy.

This archive would remain hidden for eight decades, protected by the forest’s growth and the general’s careful planning.

Trees grew over the bunker’s concealed entrance.

Leaves accumulated season after season, and nature slowly reclaimed the site.

To any casual observer, it was just another patch of unremarkable woodland, indistinguishable from thousands of others throughout Bavaria.

The secret of von Steinberg’s bunker might have died with him if not for an entirely unrelated scientific survey conducted in the summer of 2024.

A team of wildlife researchers from Munich University had been granted permission to study the forest’s ecosystem using ground penetrating radar to map underground root systems and soil composition.

They had no interest in wartime history and no reason to suspect that their routine survey would uncover one of the war’s greatest mysteries.

Dr.

Maria Hoffman adjusted her equipment one more time, wiping sweat from her forehead as the July heat pressed down through the forest canopy.

The wildlife survey was entering its third week, and the team had mapped over 40 square kilometers of the Bavarian woodland without finding anything more exciting than a few badger dens and some unusual mineral deposits.

Her ground penetrating radar had been functioning perfectly, sending electromagnetic pulses deep into the earth and painting detailed pictures of what lay beneath the forest floor.

The readings that morning started normally enough.

Root systems appeared as expected.

Soil layers showed typical stratification and occasional rocks registered as solid masses on her display screen.

But as doctor Hoffman moved her equipment across a particularly dense section of undergrowth, something anomalous appeared on her monitor.

The radar was detecting a large void approximately 4 m below the surface, far too regular in shape to be natural.

At first, she assumed it was a limestone cave or perhaps an old minehaft from Bavaria’s industrial past.

The region was dotted with abandoned mining operations, and it wouldn’t be unusual to find forgotten excavations slowly collapsing beneath the forest.

But as she expanded her scan area, the shape became more defined, more deliberate.

This wasn’t a natural cave or a random mining tunnel.

The void showed clear geometric patterns, right angles and parallel walls that could only be artificial.

Her research partner, Dr.

Klaus Weber, was initially skeptical when she called him over to examine the readings.

Weber had been conducting soil analysis 30 m away and had seen nothing unusual in his core samples.

But one look at Hoffman’s radar display changed his perspective entirely.

The underground structure was extensive, comprising multiple chambers connected by what appeared to be corridors.

Most puzzling of all, the construction seemed solid and intact, not collapsed or deteriorated like most wartime ruins.

The team spent the rest of that day carefully mapping the underground complex.

Each pass of the radar revealed new details about the hidden structure below.

The main chamber was roughly 12 m long by 8 m wide with smaller adjacent rooms branching off like the arms of a star.

The walls were thick, suggesting heavy construction, and the depth indicated serious excavation work.

This wasn’t some hastily dug shelter or temporary hiding place.

Someone had invested considerable time and resources in building whatever lay beneath their feet.

That evening, back at their temporary research station, Dr.

Hoffman contacted her department head at Munich University.

Professor Ernst Müller had overseen dozens of archaeological surveys throughout Bavaria and was familiar with the region’s history.

When Hoffman described their discovery, Müller’s response was immediate and decisive.

Work would stop until proper authorities could be notified.

The discovery was too significant and potentially too dangerous to proceed without expert oversight.

Within 48 hours, the quiet forest location was transformed into a carefully controlled excavation site.

Archaeological experts arrived from universities across Germany.

While government officials conducted hushed consultations about the legal implications of the discovery, the Bavarian State Office for Monument Protection took charge of the operation, bringing specialized equipment and personnel trained in handling sensitive historical finds.

The excavation began with extreme caution.

Eight decades of forest growth had completely concealed any surface evidence of the bunker’s entrance, and the team had to rely entirely on radar mapping to guide their digging.

Ancient trees had grown directly over the site, their massive root systems intertwined with whatever lay beneath.

Each shovel full of earth had to be carefully sifted and documented in case it contained artifacts or clues about the site’s construction.

3 days into the excavation, they hit concrete.

The discovery sent a surge of excitement through the archaeological team, confirming that their underground structure was indeed artificial and substantial.

But it also raised new questions about who had built it and when.

The concrete appeared to be of wartime vintage, rough mixed and reinforced with steel bars that had somehow avoided corrosion despite decades in the damp earth.

As more of the structure was exposed, its sophisticated design became apparent.

The entrance had been sealed with a heavy steel door painted in camouflage colors that had long since faded to rust.

Multiple ventilation shafts extended upward through the earth.

Their openings so cleverly concealed that they remained invisible even after excavation began.

Whoever built this bunker had possessed both engineering expertise and unlimited access to materials during wartime rationing.

The moment of breakthrough came on a gray Tuesday morning in late July.

After carefully removing the corroded locks and hinges, the excavation team finally opened the steel door that had sealed the bunker for eight decades.

The sound it made, a deep metallic groan echoing from the darkness below, sent chills through everyone present.

Stale air rushed out, carrying with it the musty smell of decades old confinement and something else, something that suggested human habitation.

Dr.

Hoffman was among the first to descend into the bunker, her headlamp cutting through darkness that hadn’t seen light since 1945.

What she found defied every expectation.

The interior was remarkably well preserved, protected from the elements by superior construction and careful ceiling.

Tables and chairs remained exactly where they’d been left, covered in dust, but otherwise intact.

Personal belongings were scattered throughout the space, suggesting someone had lived here for an extended period.

The main chamber was divided into distinct areas that revealed the bunker’s intended use.

One corner housed a sophisticated radio setup with equipment that looked far more advanced than standard wartime military communications.

Banks of batteries lined one wall connected to a generator that had presumably provided power for extended operations.

Charts and maps covered another wall marked with symbols and notations that would require expert analysis to decipher.

But it was the personal items that made the discovery truly extraordinary.

Military uniforms hung neatly in a makeshift closet bearing insignia that immediately identified their owner as a high-ranking German officer.

Personal photographs showed a distinguishedlooking man in vermached uniform, often pictured with other officers whose faces would be familiar to any student of World War II history.

Most significantly, a name plate on the desk identified the bunker’s occupant, General Friedrich Wilhelm Von Steinberg.

The discovery of Vonsteinberg’s identity sent shock waves through the historical community.

Here was a man who had been presumed dead for eight decades.

Yet evidence suggested he had survived in this hidden bunker for years after the wars end.

The implications were staggering.

How long had he lived here? What had he been doing during his hidden years? And most importantly, what secrets had he taken with him into this underground refuge? Dr.

Hoffman’s team worked methodically through the bunker’s contents, cataloging each item with the care reserved for the most significant archaeological discoveries.

Personal effects told the story of a man trying to maintain some semblance of civilized life in extraordinary circumstances.

Books lined improvised shelves, their pages yellowed but readable.

A chess set sat on a small table, pieces arranged in the middle of a game that would never be finished.

The radio equipment proved to be particularly intriguing.

Technical experts who examined the setup confirmed that it was capable of long range communication far beyond what would be needed for simple emergency contact.

Frequency logs found nearby suggested that Von Steinberg had been monitoring radio traffic from around the world, staying informed about global events from his hidden sanctuary.

Some entries indicated two-way communication, raising the possibility that the missing general had maintained contact with unknown parties throughout his disappearance.

A locked filing cabinet in the corner of the main chamber contained the most sensitive discoveries.

Inside were hundreds of documents, many bearing official vermached seals and classification stamps.

Military orders, intelligence reports, and correspondence between highranking German officials painted a picture of the war’s final months that differed significantly from accepted historical accounts.

Von Steinberg had apparently been collecting and preserving evidence that others wanted destroyed.

Among the most shocking discoveries were detailed reports about secret weapons programs, evacuation plans for Nazi leadership, and correspondents discussing post-war strategies.

Some documents bore signatures of officials who had supposedly died in the war’s final days, suggesting that survival and escape plans were far more extensive than previously known.

Von Steinberg had been at the center of information networks that extended far beyond his official military position.

Personal journals found throughout the bunker provided insight into the general’s mindset during his hidden years.

Early entries described his relief at escaping what he saw as an impossible situation, unable to surrender with honor, but unwilling to face certain execution for his knowledge of classified operations.

Later entries revealed growing isolation and despair as the reality of his self-imposed exile took its psychological toll.

The journals also contained detailed descriptions of supply networks that had sustained von Steinberg during his underground existence.

Local civilians, apparently sympathetic to his situation, had provided food and essential supplies in exchange for gold and other valuables he’d accumulated during his military service.

These networks had operated for years after the war, suggesting a level of organization and loyalty that historians had never suspected.

One of the most disturbing discoveries was a series of maps marking locations throughout Bavaria and Austria, annotated with dates and cryptic symbols.

These appeared to document other hidden sites, possibly additional bunkers or supply caches established as part of a broader survival network.

If von Steinberg’s operation was part of a larger system, the implications for postwar European history would be profound.

The final entries in Von Steinberg’s journals dated in the early 1,950 seconds revealed a man increasingly consumed by paranoia and regret.

He wrote of hearing voices in the forest above, of imagined pursuit by Allied investigators, and of growing certainty that his isolation would be permanent.

The entries became increasingly erratic and difficult to read, suggesting mental deterioration brought on by years of solitude and stress.

Physical evidence throughout the bunker supported the journal timeline.

Food stores had been systematically depleted over several years, while personal items showed the wear of extended use.

Most tellingly, a calendar on the wall had been meticulously maintained through 1,952 with daily marks indicating Von Steinberg’s careful attention to the passage of time during his hidden years.

The discovery of human remains in a sealed chamber at the bunker’s rear provided the final piece of the puzzle.

Forensic analysis would later confirm that the bones belonged to a male of appropriate age and build to be von Steinberg himself.

The general had died alone in his underground refuge, taking his secrets with him, but leaving behind evidence that would reshape understanding of the war’s aftermath.

News of the bunker’s discovery spread quickly through academic and government circles, but public disclosure was carefully managed.

The sensitive nature of the documents found inside required extensive review by intelligence services from multiple countries.

Many of the papers contained information that remained classified even eight decades after the wars end involving operations and individuals whose activities had never been publicly acknowledged.

International teams of historians and intelligence analysts descended on the site working to authenticate and interpret the massive document cache.

von Steinberg had preserved.

Each file told part of a larger story about the war’s final months and the complex networks that had operated behind the scenes of official military operations.

The implications extended far beyond one missing general, touching on fundamental questions about how the war had really ended and who had been involved in its conclusion.

The bunker itself became a focal point for broader questions about post-war justice and accountability.

Von Steinberg’s survival raised uncomfortable questions about other missing persons from the Nazi regime and whether the accepted narratives about their fates were as complete as historians had believed.

The forensic team that examined Fon Steinberg’s remains made discoveries that challenged everything they thought they knew about his final years.

Carbon dating of artifacts found with the body suggested he had survived in the bunker until at least 1954, nearly a decade after his disappearance.

But more puzzling were the medical supplies and prescription bottles scattered around his makeshift living quarters.

The medications were for conditions that typically affected much older individuals, suggesting von Steinberg had lived far longer than anyone imagined possible.

Dr.

Hinrich Weiss, the forensic pathologist assigned to examine the remains, found evidence of multiple healed fractures and signs of malnutrition that painted a grim picture of the general’s final years.

The bones showed stress patterns consistent with prolonged confinement and limited physical activity.

Most disturbing were marks on several ribs that appeared to be self-inflicted, possibly indicating desperate attempts at self-surgery when medical help was unavailable.

The discovery of a primitive medical station in one corner of the bunker supported this theory.

Surgical instruments, bandages, and even a cracked mirror positioned for self-examination told the story of a man forced to treat his own ailments with whatever resources he could gather.

Empty medicine bottles bore labels fromarmacies across southern Germany, suggesting his supply network had extended far beyond basic food provisions.

Among the personal effects found near von Steinberg’s remains was a leatherbound diary that differed marketkedly from his earlier military journals.

This final record written in increasingly shaky handwriting documented his growing awareness that he would never leave the bunker alive.

The entries described elaborate fantasies about returning to the surface, reuniting with family members, and revealing his story to the world.

But they also showed his gradual acceptance that isolation had become his permanent reality.

The diary’s final entries, barely legible scratches on yellowed paper, revealed the depth of von Steinberg’s psychological deterioration.

He wrote about conversations with imaginary visitors, elaborate conspiracy theories about his discovery, and paranoid fears that his food was being poisoned by unknown enemies.

The last coherent entry dated March 1,955 consisted of a single sentence repeated dozens of times.

They will never understand what we preserved.

Security cameras installed during the excavation captured something extraordinary that even seasoned investigators found difficult to explain.

Late one evening, as team members reviewed footage from the bunker’s interior, motion sensors detected movement in chambers that had been sealed for decades.

Upon investigation, they found nothing disturbed, but temperature readings showed unexplained fluctuations in areas where Von Steinberg’s personal effects were stored.

Local residents, when questioned about the bunker’s location, provided conflicting accounts that added to the mystery.

Several elderly villagers claimed their grandparents had spoken of strange lights in the forest during the 1,950 seconds, always in the exact area where the bunker was discovered.

Others described hearing machinery sounds from beneath the earth, though no mechanical equipment was found in working condition.

Most unsettling were reports of voices calling out from the woods on quiet nights, voices that seemed to come from underground.

The investigation took an unexpected turn when researchers discovered that Von Steinberg’s bunker was not unique.

Ground penetrating radar surveys of the surrounding forest revealed at least three other underground structures within a 5 kilometer radius.

Each showed similar construction techniques and appeared to be connected by a network of tunnels that had partially collapsed over the decades.

The scope of the operation was far larger than anyone had initially suspected.

Excavation of the secondary sites revealed additional caches of documents and personal belongings, but no other human remains.

These satellite bunkers appeared to have been supply depots and communication relay points, suggesting Von Steinberg had been operating a sophisticated underground network throughout his hidden years.

Radio equipment found at each location was configured to different frequencies, indicating systematic monitoring of international communications.

The document analysis revealed von Steinberg’s true purpose during his underground exile.

Rather than simply hiding from Allied justice, he had been systematically documenting and preserving evidence of war crimes and secret operations that other Nazi officials were desperate to destroy.

His bunker had served as a repository for information that could have exposed networks of collaboration and conspiracy extending far beyond Germany’s borders.

Intelligence agencies from multiple countries descended on the site as the full scope of von Steinberg’s archive became apparent.

Files contained detailed records of financial transactions, escape routes, and post-war identities provided to fleeing Nazi officials.

Some documents implicated individuals who had gone on to prominent careers in post-war Europe and America, creating a diplomatic crisis that governments were still working to resolve.

The most explosive discoveries came from a hidden compartment behind von Steinberg’s radio equipment.

Inside were photographs, correspondents, and financial records documenting a vast network of Swiss bank accounts, South American properties, and false identity papers.

The general had not only preserved evidence of war crimes, but had also maintained detailed records of the financial infrastructure that enabled Nazi officials to escape justice and rebuild their lives in exile.

Among these files were letters from individuals who had supposedly died in the war’s final days, written years after their presumed deaths from comfortable exile in Argentina and Paraguay.

Von Steinberg had been in communication with a shadow network of survivors who had successfully faked their deaths and established new identities abroad.

His bunker served as both refuge and communication hub for this underground railroad of war criminals.

The psychological profile that emerged from von Steinberg’s writings painted a complex picture of a man torn between loyalty and conscience.

Early diary entries showed genuine horror at Nazi atrocities, but later passages revealed his growing obsession with preserving evidence rather than seeking justice.

He had convinced himself that documentation was more important than accountability, that future historians would need his records to understand the truth about the war’s end.

Medical experts who studied von Steinberg’s final years identified signs of severe psychological trauma that went far beyond simple isolation.

The general had developed elaborate rituals and obsessive behaviors centered around organizing and cataloging his document collection.

He spent his final years creating detailed indexes, cross references, and summaries of information that only he would ever read.

The work had become his entire existence.

A desperate attempt to maintain purpose in a life stripped of all normal human contact.

The bunker’s ventilation system, when fully examined, revealed another layer of von Steinberg’s paranoia and ingenuity.

Multiple air shafts had been equipped with primitive but effective filtering systems designed to protect against chemical weapons.

Emergency seals could isolate the bunker completely, allowing survival for weeks without outside air.

The general had prepared for siege conditions that never materialized, leaving him trapped by his own defensive preparations.

Food storage areas throughout the complex showed evidence of careful rationing and preservation techniques that had sustained Von Steinberg for nearly a decade.

He had become expert at extending supplies, growing small quantities of vegetables in improvised planters, and even distilling alcohol from fermented organic matter.

The skills that had made him an effective military commander had been adapted for solitary survival in conditions he could never have imagined during his years of service.

The communication logs found throughout the bunker revealed the extent of Von Steinberg’s ongoing contact with the outside world during his hidden years.

He had monitored radio broadcasts from across Europe and America, staying informed about political developments, war crimes trials, and the fates of his former colleagues.

Some entries suggested he had even attempted to influence events through anonymous tips to journalists and investigators, though none of these communications were ever traced back to their source.

Personal photographs discovered in Von Steinberg’s living quarters provided glimpses into the life he had abandoned.

Images of family gatherings, military ceremonies, and peaceful moments from before the war showed a man who had once lived normally among friends and loved ones.

The contrast with his final years of isolation was stark and tragic, illustrating the complete transformation that his choices had imposed upon his existence.

The investigation team noticed that Von Steinberg had made multiple attempts to expand his underground refuge over the years.

Partially completed excavations led to dead ends where his strength or tools had proven inadequate for the task.

These abandoned projects suggested periods of manic activity alternating with depression and resignation.

The general had fought against his confinement while simultaneously making it more complete and permanent.

Technical analysis of the bunker’s construction revealed sophisticated engineering that went far beyond typical wartime fortifications.

Drainage systems prevented flooding during heavy rains.

Thermal regulation maintained stable temperatures year round and structural supports had been calculated to withstand significant ground pressure.

Von Steinberg had either possessed remarkable engineering knowledge himself or had access to expert assistance during the bunker’s construction phase.

The discovery of multiple escape routes from the bunker complex added another dimension to the mystery.

tunnels extended in several directions from the main chamber, some leading to concealed exits hundreds of meters away.

These passages showed signs of regular use during Von Steinberg’s early years underground, but appeared to have been sealed from the inside during his final period of occupation.

The general had systematically cut off his own escape routes, ensuring that his exile would be permanent.

As the excavation neared completion, investigators realized they had uncovered more than just one man’s hidden refuge.

Von Steinberg’s bunker represented a previously unknown chapter in postwar European history, revealing networks and operations that had remained secret for eight decades.

The implications extended far beyond historical curiosity, touching on fundamental questions about justice, accountability, and the long shadow cast by unresolved wartime crimes.

The general’s story was approaching its final revelation.

But the documents he had preserved would continue generating controversy and investigation for years to come.

His underground archive had become a time bomb of historical evidence, waiting eight decades to explode into public consciousness and challenge everything the world thought it knew about how the Second World War really ended ended.

The discovery of General Von Steinberg’s bunker forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about the Second World War’s aftermath.

For eight decades, we believed we understood how the conflict ended, who escaped justice, and what secrets died with the Nazi regime.

But this hidden archive beneath the Bavarian forest proves that reality was far more complex than our history books suggested.

Von Steinberg’s choice to disappear rather than surrender or flee reveals a third path that historians never considered.

He became both guardian and prisoner of information too dangerous to reveal and too important to destroy.

His self-imposed exile preserved evidence that governments wanted buried, creating a historical time capsule that has fundamentally altered our understanding of postwar Europe.

The general’s tragic end reminds us that some secrets carry too heavy a price for those who keep them.

His isolation and gradual psychological deterioration show the human cost of preserving truth in a world that wasn’t ready to hear it.

Yet his sacrifice has given future generations access to information that might otherwise have been lost forever.

Today, intelligence agencies continue analyzing the documents found in Fon Steinberg’s bunker.

Each file potentially rewriting another chapter of history.

The investigation has revealed that some mysteries are solved not by brilliant detective work, but by accident, patience, and the simple passage of time.

Sometimes the forest keeps its secrets until science gives us new eyes to see what was hidden in plain sight all along.

This story was brutal, but this story on the right hand side is even more insane.

The story you’re about to hear involves coded messages, underground networks, and a conspiracy that reaches into the highest levels of wartime command.

But most shocking of all, the general’s final recorded words suggest he knew something about the war’s outcome that no one else did.

Something that made him believe disappearing was his only option.

October 15th, 1,944.

General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steinberg stood at the window of his command post in the Bavarian Alps, watching snow fall on the mountains he’d called home for most of his military career.

At 52 years old, he was one of Germany’s most decorated officers, a brilliant tactician who had earned respect even from his enemies.

His strategic mind had helped plan some of the Vermach’s most successful early campaigns.

But now, as autumn turned to winter, even von Steinberg could see the writing on the wall.

The general wasn’t your typical Nazi officer.

Born into a Prussian military family, he’d joined the army long before Hitler’s rise to power.

His loyalty was to Germany, not to the party, a distinction that would prove crucial in the months to come.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Fon Steinberg kept detailed personal journals documenting not just military operations, but his growing concerns about the direction of the war and the regime he served.

Those journals discovered decades later reveal a man increasingly troubled by what he witnessed.

Entry after entry describes his horror at reports filtering back from the Eastern Front, his disgust with SS operations and his growing belief that Germany’s leadership had lost all connection to reality.

But Von Steinberg was also a pragmatist.

He understood that speaking out meant certain death.

So he kept his thoughts private while continuing to serve with distinction.

By early 1945, von Steinberg had been reassigned to oversee defensive preparations in the Bavarian forest region.

Officially, his mission was to coordinate with local commanders to prepare for the inevitable Allied advance.

Unofficially, he was beginning to plan something far more complex.

Intelligence reports from that period show increased radio traffic in his sector, coded transmissions that didn’t match any known German military protocols.

Something was happening in those mountains, something that wouldn’t appear in any official war records.

The first clue that von Steinberg was planning his disappearance came from his aid to camp, Lieutenant Klaus Hoffman.

Years later, Hoffman would tell Allied interrogators about the general’s increasingly secretive behavior in the final weeks of the war.

Private meetings with unknown civilians, trips into the forest that lasted for days, and most puzzling of all, requisitions for construction materials that seemed to have no military purpose.

Hoffman described finding his commander one morning in March 1945 hunched over topographical maps of the local area.

The maps were covered in markings, elevation calculations, and what appeared to be architectural sketches.

When Hoffman asked about them, Von Steinberg simply smiled and said he was preparing for the future.

At the time, the lieutenant assumed his general was planning defensive positions.

He had no idea he was witnessing the birth of one of history’s most elaborate disappearances.

The construction project began in secret sometime in February 1945.

Using a carefully selected crew of engineers and laborers, von Steinberg oversaw the excavation of what would become his hidden bunker.

The location was perfect, a remote valley deep in the Bavarian forest, accessible only by a network of hunting trails that few people knew existed.

The site was hidden by dense tree cover and positioned in such a way that it would be invisible to aerial reconnaissance.

But this wasn’t just any bunker.

The facility Von Steinberg had constructed was a marvel of engineering.

Designed not for temporary shelter, but for long-term survival.

The main chamber was reinforced with steel and concrete, equipped with its own ventilation system, water supply, and enough storage space for months of provisions.

Adjacent rooms housed a communication center, a library, and what appeared to be a workshop equipped with precision instruments.

The most intriguing aspect of the bunker was its communication capabilities.

Allied intelligence would later discover that von Steinberg had somehow acquired radio equipment far more advanced than standard military issue.

The transmitter was capable of reaching locations across Europe and beyond, suggesting that the general’s plans extended far beyond simply hiding from the advancing allies.

Construction was completed in record time with the final touches added in early April 1945.

By then, American forces were already crossing the Rine, and Soviet troops were approaching Berlin.

Germany’s defeat was no longer a question of if, but when.

Yet, Von Steinberg seemed oddly calm about the situation, as if he knew something others didn’t.

The general’s behavior in those final weeks became increasingly erratic.

He began dismissing staff, sending loyal officers away on fabricated missions, and systematically reducing the number of people who knew his whereabouts.

Those who remained described a man who seemed to be preparing for a journey, though none could say where he might be going.

Lieutenant Hoffman’s final conversation with his commander took place on April 20th, 1,945, Hitler’s birthday.

The irony wasn’t lost on Von Steinberg, who had grown to despise the man whose orders he’d been following for years.

The general handed Hoffman a sealed envelope with instructions not to open it until May 1st.

Inside was a letter that would later become one of the key pieces of evidence in understanding Von Steinberg’s disappearance.

The letter was brief but cryptic.

Von Steinberg wrote that he could no longer serve a cause he didn’t believe in, but neither could he surrender to forces that might use him for propaganda purposes.

He spoke of a third option, a path that would allow him to serve his true country while avoiding the fate that awaited so many of his colleagues.

The letter ended with a promise that someday when the time was right, the truth would be revealed.

On the morning of April 25th, 1,945, General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steinberg left his command post for what would be the last time.

He told his remaining staff that he was conducting a final inspection of defensive positions and would return by evening.

He never did.

When search parties were sent out the following day, they found no trace of the general or the vehicle he’d been driving.

The official report filed by German command stated that General von Steinberg was missing in action, presumed killed in combat with advancing Allied forces.

No body was ever found, no witnesses came forward, and no evidence of his fate was discovered.

As far as the military bureaucracy was concerned, he had simply vanished into the chaos of Germany’s final defeat.

But von Steinberg hadn’t vanished at all.

He had simply activated the most carefully planned disappearance in military history.

While Allied and German forces battled across the German countryside, the general was settling into his hidden bunker, beginning a secret existence that would last for years.

He had enough supplies to survive for months.

And more importantly, he had a plan for what would come next.

The bunker’s communication equipment allowed von Steinberg to monitor the war’s progress from his hidden refuge.

He listened as Berlin fell, as Hitler died in his own bunker, and as Germany formally surrendered.

But instead of emerging to face whatever justice awaited former Vermacht officers, the general remained hidden, waiting for reasons that wouldn’t become clear for decades.

Allied intelligence services eventually became aware of Von Steinberg’s disappearance.

But with thousands of German military personnel unaccounted for in the war’s aftermath, one missing general wasn’t a high priority.

Some investigators theorized that he’d fled to South America like other Nazi officials.

Others assumed he’d been killed in the final battles and his body never recovered.

None suspected that he was living just miles from where he’d last been seen, hidden beneath the forest floor.

The search for Von Steinberg continued sporadically throughout the late 100, 940 seconds, and early 1,950 seconds.

Nazi hunters followed leads across Europe and South America, always one step behind a ghost that had never actually left Germany.

Intelligence files from the period show that various agencies investigated reported sightings in Argentina, Paraguay, and even the United States.

But none of these leads proved credible.

Meanwhile, deep in the Bavarian forest, Von Steinberg was adapting to his new existence.

The bunker’s ventilation system allowed him to remain underground for extended periods, while carefully planned supply runs under cover of darkness kept him fed and informed about the changing world above.

He had become a hermit by choice, a man who had erased himself from history while remaining very much alive.

The general’s journals from this period, later discovered in the bunker, reveal a complex psychological transformation.

The military officer who had once commanded thousands of men was learning to live in complete solitude sustained only by his conviction that he had chosen the right path.

He wrote extensively about his reasons for disappearing, his hopes for Germany’s future, and his growing belief that he was preserving something important for future generations.

By 1950, most official searches for von Steinberg had been called off.

The world had moved on to new conflicts and new concerns, and the missing general had become just another unsolved mystery from the war.

His name appeared occasionally in books about Nazi fugitives, but without new evidence, there was little to distinguish his case from hundreds of others.

What no one realized was that Fon Steinberg’s disappearance was only the beginning of his story.

The bunker he’d constructed was designed for more than simple survival.

It was a repository, a hidden archive containing documents and artifacts that would prove invaluable to future historians.

The general had spent his final months of official service gathering evidence, copying documents, and preserving records that others were eager to destroy.

This archive would remain hidden for eight decades, protected by the forest’s growth and the general’s careful planning.

Trees grew over the bunker’s concealed entrance.

Leaves accumulated season after season, and nature slowly reclaimed the site.

To any casual observer, it was just another patch of unremarkable woodland, indistinguishable from thousands of others throughout Bavaria.

The secret of von Steinberg’s bunker might have died with him if not for an entirely unrelated scientific survey conducted in the summer of 2024.

A team of wildlife researchers from Munich University had been granted permission to study the forest’s ecosystem using ground penetrating radar to map underground root systems and soil composition.

They had no interest in wartime history and no reason to suspect that their routine survey would uncover one of the war’s greatest mysteries.

Dr.

Maria Hoffman adjusted her equipment one more time, wiping sweat from her forehead as the July heat pressed down through the forest canopy.

The wildlife survey was entering its third week, and the team had mapped over 40 square kilometers of the Bavarian woodland without finding anything more exciting than a few badger dens and some unusual mineral deposits.

Her ground penetrating radar had been functioning perfectly, sending electromagnetic pulses deep into the earth and painting detailed pictures of what lay beneath the forest floor.

The readings that morning started normally enough.

Root systems appeared as expected.

Soil layers showed typical stratification and occasional rocks registered as solid masses on her display screen.

But as doctor Hoffman moved her equipment across a particularly dense section of undergrowth, something anomalous appeared on her monitor.

The radar was detecting a large void approximately 4 m below the surface, far too regular in shape to be natural.

At first, she assumed it was a limestone cave or perhaps an old minehaft from Bavaria’s industrial past.

The region was dotted with abandoned mining operations, and it wouldn’t be unusual to find forgotten excavations slowly collapsing beneath the forest.

But as she expanded her scan area, the shape became more defined, more deliberate.

This wasn’t a natural cave or a random mining tunnel.

The void showed clear geometric patterns, right angles and parallel walls that could only be artificial.

Her research partner, Dr.

Klaus Weber, was initially skeptical when she called him over to examine the readings.

Weber had been conducting soil analysis 30 m away and had seen nothing unusual in his core samples.

But one look at Hoffman’s radar display changed his perspective entirely.

The underground structure was extensive, comprising multiple chambers connected by what appeared to be corridors.

Most puzzling of all, the construction seemed solid and intact, not collapsed or deteriorated like most wartime ruins.

The team spent the rest of that day carefully mapping the underground complex.

Each pass of the radar revealed new details about the hidden structure below.

The main chamber was roughly 12 m long by 8 m wide with smaller adjacent rooms branching off like the arms of a star.

The walls were thick, suggesting heavy construction, and the depth indicated serious excavation work.

This wasn’t some hastily dug shelter or temporary hiding place.

Someone had invested considerable time and resources in building whatever lay beneath their feet.

That evening, back at their temporary research station, Dr.

Hoffman contacted her department head at Munich University.

Professor Ernst Müller had overseen dozens of archaeological surveys throughout Bavaria and was familiar with the region’s history.

When Hoffman described their discovery, Müller’s response was immediate and decisive.

Work would stop until proper authorities could be notified.

The discovery was too significant and potentially too dangerous to proceed without expert oversight.

Within 48 hours, the quiet forest location was transformed into a carefully controlled excavation site.

Archaeological experts arrived from universities across Germany.

While government officials conducted hushed consultations about the legal implications of the discovery, the Bavarian State Office for Monument Protection took charge of the operation, bringing specialized equipment and personnel trained in handling sensitive historical finds.

The excavation began with extreme caution.

Eight decades of forest growth had completely concealed any surface evidence of the bunker’s entrance, and the team had to rely entirely on radar mapping to guide their digging.

Ancient trees had grown directly over the site, their massive root systems intertwined with whatever lay beneath.

Each shovel full of earth had to be carefully sifted and documented in case it contained artifacts or clues about the site’s construction.

3 days into the excavation, they hit concrete.

The discovery sent a surge of excitement through the archaeological team, confirming that their underground structure was indeed artificial and substantial.

But it also raised new questions about who had built it and when.

The concrete appeared to be of wartime vintage, rough mixed and reinforced with steel bars that had somehow avoided corrosion despite decades in the damp earth.

As more of the structure was exposed, its sophisticated design became apparent.

The entrance had been sealed with a heavy steel door painted in camouflage colors that had long since faded to rust.

Multiple ventilation shafts extended upward through the earth.

Their openings so cleverly concealed that they remained invisible even after excavation began.

Whoever built this bunker had possessed both engineering expertise and unlimited access to materials during wartime rationing.

The moment of breakthrough came on a gray Tuesday morning in late July.

After carefully removing the corroded locks and hinges, the excavation team finally opened the steel door that had sealed the bunker for eight decades.

The sound it made, a deep metallic groan echoing from the darkness below, sent chills through everyone present.

Stale air rushed out, carrying with it the musty smell of decades old confinement and something else, something that suggested human habitation.

Dr.

Hoffman was among the first to descend into the bunker, her headlamp cutting through darkness that hadn’t seen light since 1945.

What she found defied every expectation.

The interior was remarkably well preserved, protected from the elements by superior construction and careful ceiling.

Tables and chairs remained exactly where they’d been left, covered in dust, but otherwise intact.

Personal belongings were scattered throughout the space, suggesting someone had lived here for an extended period.

The main chamber was divided into distinct areas that revealed the bunker’s intended use.

One corner housed a sophisticated radio setup with equipment that looked far more advanced than standard wartime military communications.

Banks of batteries lined one wall connected to a generator that had presumably provided power for extended operations.

Charts and maps covered another wall marked with symbols and notations that would require expert analysis to decipher.

But it was the personal items that made the discovery truly extraordinary.

Military uniforms hung neatly in a makeshift closet bearing insignia that immediately identified their owner as a high-ranking German officer.

Personal photographs showed a distinguishedlooking man in vermached uniform, often pictured with other officers whose faces would be familiar to any student of World War II history.

Most significantly, a name plate on the desk identified the bunker’s occupant, General Friedrich Wilhelm Von Steinberg.

The discovery of Vonsteinberg’s identity sent shock waves through the historical community.

Here was a man who had been presumed dead for eight decades.

Yet evidence suggested he had survived in this hidden bunker for years after the wars end.

The implications were staggering.

How long had he lived here? What had he been doing during his hidden years? And most importantly, what secrets had he taken with him into this underground refuge? Dr.

Hoffman’s team worked methodically through the bunker’s contents, cataloging each item with the care reserved for the most significant archaeological discoveries.

Personal effects told the story of a man trying to maintain some semblance of civilized life in extraordinary circumstances.

Books lined improvised shelves, their pages yellowed but readable.

A chess set sat on a small table, pieces arranged in the middle of a game that would never be finished.

The radio equipment proved to be particularly intriguing.

Technical experts who examined the setup confirmed that it was capable of long range communication far beyond what would be needed for simple emergency contact.

Frequency logs found nearby suggested that Von Steinberg had been monitoring radio traffic from around the world, staying informed about global events from his hidden sanctuary.

Some entries indicated two-way communication, raising the possibility that the missing general had maintained contact with unknown parties throughout his disappearance.

A locked filing cabinet in the corner of the main chamber contained the most sensitive discoveries.

Inside were hundreds of documents, many bearing official vermached seals and classification stamps.

Military orders, intelligence reports, and correspondence between highranking German officials painted a picture of the war’s final months that differed significantly from accepted historical accounts.

Von Steinberg had apparently been collecting and preserving evidence that others wanted destroyed.

Among the most shocking discoveries were detailed reports about secret weapons programs, evacuation plans for Nazi leadership, and correspondents discussing post-war strategies.

Some documents bore signatures of officials who had supposedly died in the war’s final days, suggesting that survival and escape plans were far more extensive than previously known.

Von Steinberg had been at the center of information networks that extended far beyond his official military position.

Personal journals found throughout the bunker provided insight into the general’s mindset during his hidden years.

Early entries described his relief at escaping what he saw as an impossible situation, unable to surrender with honor, but unwilling to face certain execution for his knowledge of classified operations.

Later entries revealed growing isolation and despair as the reality of his self-imposed exile took its psychological toll.

The journals also contained detailed descriptions of supply networks that had sustained von Steinberg during his underground existence.

Local civilians, apparently sympathetic to his situation, had provided food and essential supplies in exchange for gold and other valuables he’d accumulated during his military service.

These networks had operated for years after the war, suggesting a level of organization and loyalty that historians had never suspected.

One of the most disturbing discoveries was a series of maps marking locations throughout Bavaria and Austria, annotated with dates and cryptic symbols.

These appeared to document other hidden sites, possibly additional bunkers or supply caches established as part of a broader survival network.

If von Steinberg’s operation was part of a larger system, the implications for postwar European history would be profound.

The final entries in Von Steinberg’s journals dated in the early 1,950 seconds revealed a man increasingly consumed by paranoia and regret.

He wrote of hearing voices in the forest above, of imagined pursuit by Allied investigators, and of growing certainty that his isolation would be permanent.

The entries became increasingly erratic and difficult to read, suggesting mental deterioration brought on by years of solitude and stress.

Physical evidence throughout the bunker supported the journal timeline.

Food stores had been systematically depleted over several years, while personal items showed the wear of extended use.

Most tellingly, a calendar on the wall had been meticulously maintained through 1,952 with daily marks indicating Von Steinberg’s careful attention to the passage of time during his hidden years.

The discovery of human remains in a sealed chamber at the bunker’s rear provided the final piece of the puzzle.

Forensic analysis would later confirm that the bones belonged to a male of appropriate age and build to be von Steinberg himself.

The general had died alone in his underground refuge, taking his secrets with him, but leaving behind evidence that would reshape understanding of the war’s aftermath.

News of the bunker’s discovery spread quickly through academic and government circles, but public disclosure was carefully managed.

The sensitive nature of the documents found inside required extensive review by intelligence services from multiple countries.

Many of the papers contained information that remained classified even eight decades after the wars end involving operations and individuals whose activities had never been publicly acknowledged.

International teams of historians and intelligence analysts descended on the site working to authenticate and interpret the massive document cache.

von Steinberg had preserved.

Each file told part of a larger story about the war’s final months and the complex networks that had operated behind the scenes of official military operations.

The implications extended far beyond one missing general, touching on fundamental questions about how the war had really ended and who had been involved in its conclusion.

The bunker itself became a focal point for broader questions about post-war justice and accountability.

Von Steinberg’s survival raised uncomfortable questions about other missing persons from the Nazi regime and whether the accepted narratives about their fates were as complete as historians had believed.

The forensic team that examined Fon Steinberg’s remains made discoveries that challenged everything they thought they knew about his final years.

Carbon dating of artifacts found with the body suggested he had survived in the bunker until at least 1954, nearly a decade after his disappearance.

But more puzzling were the medical supplies and prescription bottles scattered around his makeshift living quarters.

The medications were for conditions that typically affected much older individuals, suggesting von Steinberg had lived far longer than anyone imagined possible.

Dr.

Hinrich Weiss, the forensic pathologist assigned to examine the remains, found evidence of multiple healed fractures and signs of malnutrition that painted a grim picture of the general’s final years.

The bones showed stress patterns consistent with prolonged confinement and limited physical activity.

Most disturbing were marks on several ribs that appeared to be self-inflicted, possibly indicating desperate attempts at self-surgery when medical help was unavailable.

The discovery of a primitive medical station in one corner of the bunker supported this theory.

Surgical instruments, bandages, and even a cracked mirror positioned for self-examination told the story of a man forced to treat his own ailments with whatever resources he could gather.

Empty medicine bottles bore labels fromarmacies across southern Germany, suggesting his supply network had extended far beyond basic food provisions.

Among the personal effects found near von Steinberg’s remains was a leatherbound diary that differed marketkedly from his earlier military journals.

This final record written in increasingly shaky handwriting documented his growing awareness that he would never leave the bunker alive.

The entries described elaborate fantasies about returning to the surface, reuniting with family members, and revealing his story to the world.

But they also showed his gradual acceptance that isolation had become his permanent reality.

The diary’s final entries, barely legible scratches on yellowed paper, revealed the depth of von Steinberg’s psychological deterioration.

He wrote about conversations with imaginary visitors, elaborate conspiracy theories about his discovery, and paranoid fears that his food was being poisoned by unknown enemies.

The last coherent entry dated March 1,955 consisted of a single sentence repeated dozens of times.

They will never understand what we preserved.

Security cameras installed during the excavation captured something extraordinary that even seasoned investigators found difficult to explain.

Late one evening, as team members reviewed footage from the bunker’s interior, motion sensors detected movement in chambers that had been sealed for decades.

Upon investigation, they found nothing disturbed, but temperature readings showed unexplained fluctuations in areas where Von Steinberg’s personal effects were stored.

Local residents, when questioned about the bunker’s location, provided conflicting accounts that added to the mystery.

Several elderly villagers claimed their grandparents had spoken of strange lights in the forest during the 1,950 seconds, always in the exact area where the bunker was discovered.

Others described hearing machinery sounds from beneath the earth, though no mechanical equipment was found in working condition.

Most unsettling were reports of voices calling out from the woods on quiet nights, voices that seemed to come from underground.

The investigation took an unexpected turn when researchers discovered that Von Steinberg’s bunker was not unique.

Ground penetrating radar surveys of the surrounding forest revealed at least three other underground structures within a 5 kilometer radius.

Each showed similar construction techniques and appeared to be connected by a network of tunnels that had partially collapsed over the decades.

The scope of the operation was far larger than anyone had initially suspected.

Excavation of the secondary sites revealed additional caches of documents and personal belongings, but no other human remains.

These satellite bunkers appeared to have been supply depots and communication relay points, suggesting Von Steinberg had been operating a sophisticated underground network throughout his hidden years.

Radio equipment found at each location was configured to different frequencies, indicating systematic monitoring of international communications.

The document analysis revealed von Steinberg’s true purpose during his underground exile.

Rather than simply hiding from Allied justice, he had been systematically documenting and preserving evidence of war crimes and secret operations that other Nazi officials were desperate to destroy.

His bunker had served as a repository for information that could have exposed networks of collaboration and conspiracy extending far beyond Germany’s borders.

Intelligence agencies from multiple countries descended on the site as the full scope of von Steinberg’s archive became apparent.

Files contained detailed records of financial transactions, escape routes, and post-war identities provided to fleeing Nazi officials.

Some documents implicated individuals who had gone on to prominent careers in post-war Europe and America, creating a diplomatic crisis that governments were still working to resolve.

The most explosive discoveries came from a hidden compartment behind von Steinberg’s radio equipment.

Inside were photographs, correspondents, and financial records documenting a vast network of Swiss bank accounts, South American properties, and false identity papers.

The general had not only preserved evidence of war crimes, but had also maintained detailed records of the financial infrastructure that enabled Nazi officials to escape justice and rebuild their lives in exile.

Among these files were letters from individuals who had supposedly died in the war’s final days, written years after their presumed deaths from comfortable exile in Argentina and Paraguay.

Von Steinberg had been in communication with a shadow network of survivors who had successfully faked their deaths and established new identities abroad.

His bunker served as both refuge and communication hub for this underground railroad of war criminals.

The psychological profile that emerged from von Steinberg’s writings painted a complex picture of a man torn between loyalty and conscience.

Early diary entries showed genuine horror at Nazi atrocities, but later passages revealed his growing obsession with preserving evidence rather than seeking justice.

He had convinced himself that documentation was more important than accountability, that future historians would need his records to understand the truth about the war’s end.

Medical experts who studied von Steinberg’s final years identified signs of severe psychological trauma that went far beyond simple isolation.

The general had developed elaborate rituals and obsessive behaviors centered around organizing and cataloging his document collection.

He spent his final years creating detailed indexes, cross references, and summaries of information that only he would ever read.

The work had become his entire existence.

A desperate attempt to maintain purpose in a life stripped of all normal human contact.

The bunker’s ventilation system, when fully examined, revealed another layer of von Steinberg’s paranoia and ingenuity.

Multiple air shafts had been equipped with primitive but effective filtering systems designed to protect against chemical weapons.

Emergency seals could isolate the bunker completely, allowing survival for weeks without outside air.

The general had prepared for siege conditions that never materialized, leaving him trapped by his own defensive preparations.

Food storage areas throughout the complex showed evidence of careful rationing and preservation techniques that had sustained Von Steinberg for nearly a decade.

He had become expert at extending supplies, growing small quantities of vegetables in improvised planters, and even distilling alcohol from fermented organic matter.

The skills that had made him an effective military commander had been adapted for solitary survival in conditions he could never have imagined during his years of service.

The communication logs found throughout the bunker revealed the extent of Von Steinberg’s ongoing contact with the outside world during his hidden years.

He had monitored radio broadcasts from across Europe and America, staying informed about political developments, war crimes trials, and the fates of his former colleagues.

Some entries suggested he had even attempted to influence events through anonymous tips to journalists and investigators, though none of these communications were ever traced back to their source.

Personal photographs discovered in Von Steinberg’s living quarters provided glimpses into the life he had abandoned.

Images of family gatherings, military ceremonies, and peaceful moments from before the war showed a man who had once lived normally among friends and loved ones.

The contrast with his final years of isolation was stark and tragic, illustrating the complete transformation that his choices had imposed upon his existence.

The investigation team noticed that Von Steinberg had made multiple attempts to expand his underground refuge over the years.

Partially completed excavations led to dead ends where his strength or tools had proven inadequate for the task.

These abandoned projects suggested periods of manic activity alternating with depression and resignation.

The general had fought against his confinement while simultaneously making it more complete and permanent.

Technical analysis of the bunker’s construction revealed sophisticated engineering that went far beyond typical wartime fortifications.

Drainage systems prevented flooding during heavy rains.

Thermal regulation maintained stable temperatures year round and structural supports had been calculated to withstand significant ground pressure.

Von Steinberg had either possessed remarkable engineering knowledge himself or had access to expert assistance during the bunker’s construction phase.

The discovery of multiple escape routes from the bunker complex added another dimension to the mystery.

tunnels extended in several directions from the main chamber, some leading to concealed exits hundreds of meters away.

These passages showed signs of regular use during Von Steinberg’s early years underground, but appeared to have been sealed from the inside during his final period of occupation.

The general had systematically cut off his own escape routes, ensuring that his exile would be permanent.

As the excavation neared completion, investigators realized they had uncovered more than just one man’s hidden refuge.

Von Steinberg’s bunker represented a previously unknown chapter in postwar European history, revealing networks and operations that had remained secret for eight decades.

The implications extended far beyond historical curiosity, touching on fundamental questions about justice, accountability, and the long shadow cast by unresolved wartime crimes.

The general’s story was approaching its final revelation.

But the documents he had preserved would continue generating controversy and investigation for years to come.

His underground archive had become a time bomb of historical evidence, waiting eight decades to explode into public consciousness and challenge everything the world thought it knew about how the Second World War really ended ended.

The discovery of General Von Steinberg’s bunker forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about the Second World War’s aftermath.

For eight decades, we believed we understood how the conflict ended, who escaped justice, and what secrets died with the Nazi regime.

But this hidden archive beneath the Bavarian forest proves that reality was far more complex than our history books suggested.

Von Steinberg’s choice to disappear rather than surrender or flee reveals a third path that historians never considered.

He became both guardian and prisoner of information too dangerous to reveal and too important to destroy.

His self-imposed exile preserved evidence that governments wanted buried, creating a historical time capsule that has fundamentally altered our understanding of postwar Europe.