The car had been sitting in the canyon for 13 years, hidden from human eyes.

And when it was finally found, something was discovered inside that made even seasoned detectives shudder.

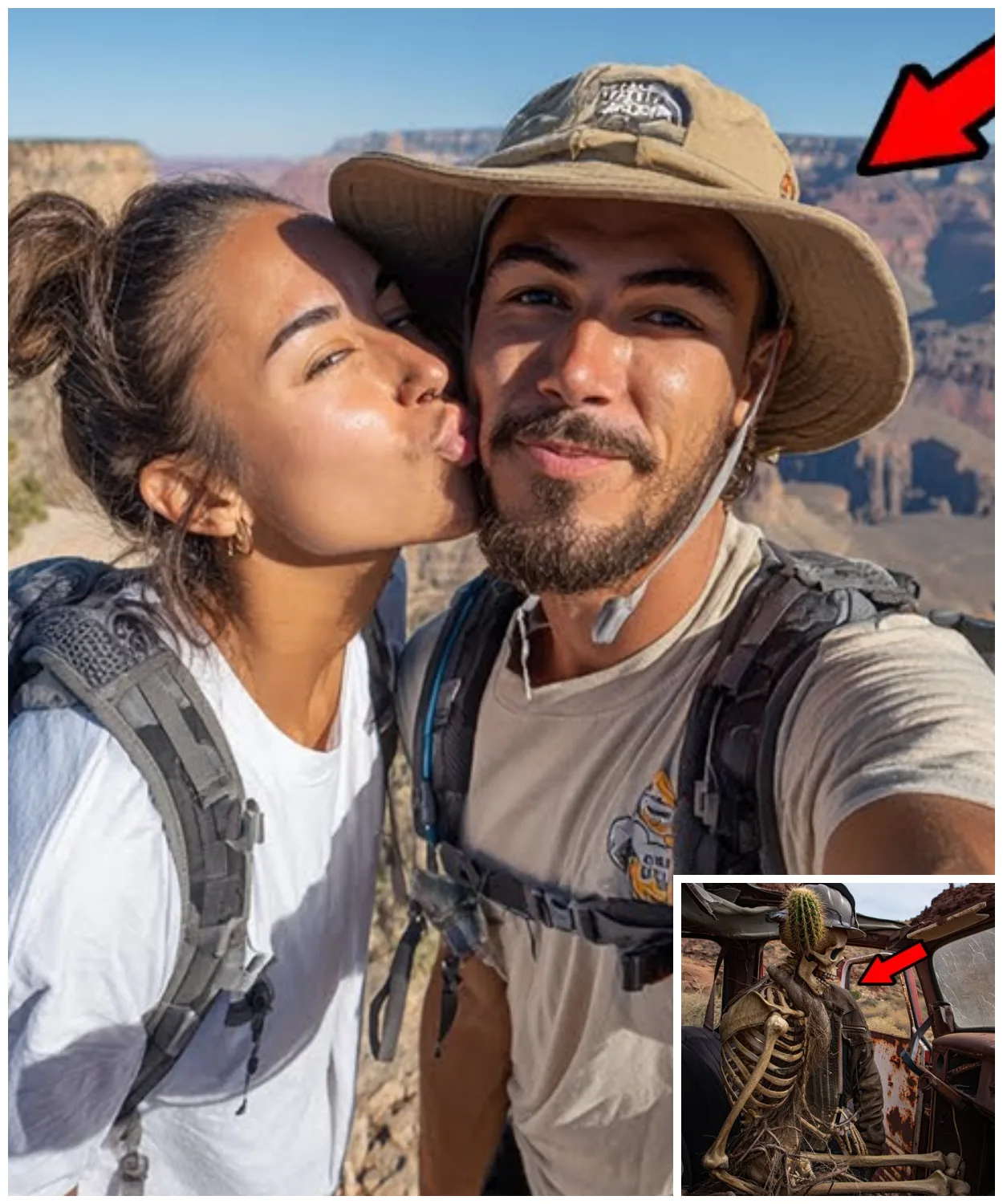

Two skeletons in the front seats with a 4-ft cactus growing through their rib cages, its roots intertwined with human bones, creating a gruesome composition of death and life.

It was not just a tragedy.

It was a work of art created by a madman who turned other people’s deaths into his installations.

And this was just one of seven of his works scattered across the vast California desert.

If you thought you knew the limits of human madness, this story will prove you wrong.

Stay tuned to find out how one man turned Death Valley into his own personal gallery of horror.

And be sure to write in the comments what you would do if you stumbled upon such a find in the desert.

Can this be considered art? Or is it pure evil? July 2004 was particularly hot in Southern California.

The temperature in Death Valley rose to 52° C, breaking all records for the last decade.

But for 26-year-old Emily Harrison and her 28-year-old husband, Jason, it was a month of happiness and new beginnings.

They had gotten married just three weeks earlier in a small church in San Diego in the presence of 70 guests to the sound of organ music and the blessings of their parents.

Emily worked as a nurse at Ray Children’s Hospital where she was loved for her gentle nature and endless patience with young patients.

Colleagues recalled how she would bring toys from home to cheer up children undergoing chemotherapy.

Jason taught history at Patrick Henry High School and coached the school basketball team on weekends.

Friends described him as a man who never raised his voice and always found time to listen to other people’s problems.

Their love story began three years ago at a party thrown by mutual friends.

Emily told her friends that she knew from the first glance that he was the one.

Jason was more cautious, but after a month of dating, he couldn’t imagine his life without her.

He proposed at La Hoya Cove Beach at sunset, kneeling on the wet sand as the waves rolled in and seagulls circled overhead.

The wedding was perfect.

Emily wore a white lace dress that her mother had kept for 30 years since her own wedding.

Jason wore a dark blue suit and a tie with thin silver stripes.

They danced their first dance to Eda James’s at last, and all the guests noticed how they looked at each other as if there was no one else in the room.

They decided to spend their honeymoon in an unusual way.

Instead of the traditional beaches of Hawaii or the romantic streets of Paris, the newlyweds chose to travel through the national parks of the West Coast.

Emily had always dreamed of seeing Death Valley, a place that fascinated her with its harsh beauty and geological history dating back millions of years.

Jason wanted to show her Zabriski Point Canyon at sunrise when the first rays of the sun paint the ancient rocks in shades of gold and orange.

They left San Diego on July 22nd in a silver 2002 Toyota Camry that Jason had bought a year ago.

The car was reliable with only 48,000 mi on the odometer and had recently undergone a full service.

In the trunk were two backpacks with clothes, a camping tent, sleeping bags, folding chairs, and a cooler with food and drinks.

Jason checked the tire pressure twice before leaving and filled the gas tank.

Emily’s mother, Caroline, saw them off with a heavy heart.

She asked her daughter to call every evening, no matter where they were.

Emily laughed and promised, even though she knew that cell phone reception in the desert was often spotty.

The last thing Caroline said as they got into the car, was to be careful and drink plenty of water.

In the desert, you can’t underestimate the heat.

On July 23rd, at p.m., Emily called her mother from a motel in the town of Baker, California.

This was her last contact with her family.

She said they were staying the night and planned to leave early in the morning for Death Valley, hoping to reach Zabriski Point by sunrise.

Emily’s voice sounded happy and excited.

She talked about how beautiful the desert was along the way, how they stopped to take pictures of the sunset over the dunes, how Jason showed her the constellations in the incredibly clear sky.

Caroline asked if they had brought enough water.

Emily assured her that they had 10 1.5 L bottles, plus several cans of soda in an ice cooler.

Jason studied the maps and planned the route.

They planned to stick to the main roads and visit several famous landmarks, Badwater Basin, the lowest point in North America, Artists Pallet with its colorful rock formations, and of course, Zabriski Point.

The conversation lasted 14 minutes.

Mother and daughter discussed the wedding, the guests, and the gifts.

Emily thanked her for organizing everything and said it was the best day of her life.

At the end of the conversation, she said, “I love you, Mom.

See you in a week.” Caroline replied with the same and asked her to call again tomorrow evening.

Emily promised, but warned that the connection might be poor.

On July 24th, they left the motel at a.m.

according to the parking lot security camera footage.

Jason was driving and Emily was in the passenger seat.

They were dressed in light summer clothes, t-shirts, and shorts.

In the back seat were backpacks, a cooler, a Canon EOS camera, binoculars, and a Death Valley travel guide.

The sun was rising above the horizon as they entered the national park.

The air was still relatively cool, around 28° C.

But in Death Valley, the temperature rises rapidly.

By noon, the thermometers were already showing 45° in the shade, and in the sun, the asphalt was heated to 80°.

They visited the Furnus Creek Visitor Center, where a park ranger had seen them around 7 in the morning.

He remembered the young couple because they asked about less touristy roots.

Jason was interested in old mines and abandoned roads.

The ranger warned them to stick to the main roads, especially in such heat and not to drive on dirt roads without a four-wheel drive vehicle.

Jason nodded and thanked him for the advice.

But then they disappeared.

No calls, no messages, no credit card transactions.

The surveillance cameras at the park exit didn’t catch them.

The silver Toyota Camry vanished into the endless desert as if swallowed up by the dunes and rocks.

On the evening of July 25th, Caroline Harrison began to worry.

Emily hadn’t called as promised.

Her daughter’s cell phone was unavailable.

Calls went straight to voicemail.

Caroline told herself it was just bad reception in the desert, that the kids were busy sightseeing and had forgotten to call.

But a mother’s heart sensed something was wrong.

On the morning of July 26th, she called Jason’s parents, Robert and Patricia Harrison.

They hadn’t heard from their son either, and were starting to worry.

Robert called the San Diego police, but they explained that adults have the right not to be in contact, and 48 hours is not enough time to declare them missing.

The officer advised waiting another day.

On July 27th, after three days without contact, the parents insisted on filing an official report.

The San Diego Police Department contacted the National Park Service.

The search began.

Rangers checked the main roads and popular spots in Death Valley.

They found several silver Toyota Camry and parking lots, but none belonged to the Harrisons.

The search team was expanded.

A helicopter with thermal imaging was brought in to scan the area from the air, looking for signs of life or a stranded vehicle.

Volunteers from the local community organized a ground search, combing the most accessible areas on foot.

Friends and relatives distributed flyers with photos of the newlyweds and a description of the car.

Emily’s mother gave an interview to the local television station KGTV San Diego.

She stood in front of the camera with a trembling voice and tears in her eyes, begging anyone who had seen her daughter or son-in-law to contact the police.

Behind her hung a wedding photo of the newlyweds, smiling, happy, full of hope for the future.

The broadcast was shown on the evening news and the phones at the police station did not stop ringing for 3 days.

But all the calls led nowhere.

Someone saw a similar couple at a roadside cafe in Shosonyi.

It turned out to be other tourists.

Someone swore they saw a silver Camry on the side of Highway 190.

The car belonged to a local resident.

Every lead was checked and dismissed.

The Harrison seemed to have vanished into thin air.

After a week of searching, the park’s chief ranger, Thomas Macdonald, held a press conference.

He announced that despite intensive efforts, including flying over more than 2,000 square miles of territory and combing all major routes on the ground, no traces of the missing couple or their car had been found.

He noted that Death Valley is a dangerous place, especially in the summer, and even experienced travelers can get into trouble if they stray from the beaten path.

The ranger also mentioned one disturbing detail.

There are hundreds of old abandoned mountain roads in the park, left over from the gold rush and borax mining of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Many of these roads are not marked on modern maps, and some are blocked by landslides or washed out by floods.

If the Harrison’s turned onto one of these roads, they could have become stuck in a place inaccessible to a normal search patrol.

As weeks and then months passed without a breakthrough in the case, various theories began to emerge about what had happened to the newlyweds.

Some were plausible, others bordered on paranoia and conspiracy theory.

The first and most obvious theory was that the couple had gotten lost and died of dehydration and heat stroke.

Death Valley holds the sad record as one of the hottest places on Earth where temperatures can kill an unprepared person in a matter of hours.

If their car had broken down or got stuck in a remote location, they could have run out of water long before help could arrive.

Detective Mark Rivera of the Inyo County Sheriff’s Department, who was in charge of the investigation, leaned toward this version.

He pointed to statistics.

Hundreds of people go missing in American national parks every year, and not all of them are found alive.

The desert is merciless.

It does not forgive mistakes.

One wrong turn, one miscalculation of distance or fuel supply, and you find yourself in mortal danger.

The second theory, supported by some friends and relatives, was that the newlyweds had been victims of a crime.

Perhaps they had met someone on the road who attacked them, killed them, and hid their bodies.

This version seemed unlikely given the low population density in the area, but it could not be completely ruled out.

Detective Rivera checked the crime records for Death Valley and the surrounding area for the past 20 years.

There had been very few serious crimes against tourists.

The region was one of the safest in California in terms of violent crime.

Nevertheless, he interviewed all known offenders living within a 100 miles of the park.

Alibis were checked, but no connections to the disappearance were found.

The third theory, the strangest, came from internet forums and blogs about paranormal phenomena.

Some claimed that the Harrisons had encountered something inexplicable, a UFO, a time portal, or some other anomaly that supposedly filled the desert.

These theories did not merit serious consideration, but they spread on social media, creating an aura of mysticism around the disappearance.

Jason’s father, Robert, did not believe in any of the alternative theories.

He was a practical engineer accustomed to logic and facts.

He organized private search expeditions, hiring professional trackers, and guides who knew every corner of Death Valley.

They explored abandoned mines, canyons, and old geologists camps.

But the desert kept its secrets.

Emily’s mother, Caroline, reacted differently.

She couldn’t accept the idea that her daughter was dead.

She believed that somewhere, somehow, Emily and Jason were still alive, perhaps suffering from amnesia or being held against their will.

She regularly checked hospital databases across the country, looking for unidentified patients who might match her daughter’s description.

Each time, her hopes were dashed by reality.

By the end of 2004, the official search had been called off.

The Harrison’s case was classified as a cold case.

The police kept all the evidence they had collected and promised to resume their work if new leads emerged.

But with each passing month, the likelihood of finding something new became slimmer and slimmer.

Years passed.

2005 6 7.

Life went on for everyone except the Harrison’s families.

The parents never gave up hope.

Even though their minds told them there was almost no hope, they celebrated their children’s birthdays by baking cakes and lighting candles in empty rooms.

They kept Emily and Jason’s apartment untouched like a museum of their former life.

Clothes in the closets, dishes on the shelves, photographs on the walls.

Caroline created a Facebook page dedicated to the search for her daughter.

She posted regular updates, shared memories, and posted old photos.

The page was read by several thousand people, many of whom had never known Emily personally, but felt a connection to her story.

People wrote words of support, promised to pray, and offered their theories.

Detective Rivera did not forget about the case, even though it had been officially closed.

Every few months, he would return to the investigation files, reread the statements, study the maps, hoping to notice something that had been overlooked before.

He understood that with each passing year, the chances of a breakthrough were diminishing.

But he couldn’t just forget about the young couple whose lives had been cut short at the very beginning.

In 2010, 6 years after the disappearance, Rivera received a call from a colleague in Nevada.

A skeleton had been found in a wrecked car in the desert near the state border.

The description matched Jason Harrison’s height and age.

Rivera immediately contacted his parents and asked for DNA samples for comparison.

2 weeks of agonizing waiting ended in disappointment.

The remains belonged to another person who had disappeared in 2007.

This was not the only false alarm.

Over the years, there were reports of bones, clothing, and personal items found in various parts of the desert.

Each time, tests were conducted.

Each time, the results were negative.

The families went through an emotional roller coaster from bursts of hope to deep disappointment.

By 2015, even the most optimistic relatives were beginning to lose faith.

11 years had passed.

If the Harrisons had died in the desert, their remains could have long since been scattered by scavengers or buried by sandstorms.

Death Valley is a place where nature quickly erases traces of human presence.

Robert Harrison, Jason’s father, died of a heart attack in 2016.

Doctors said it was the result of chronic stress and depression that had been undermining his health for years.

He never found out what happened to his son.

His last words before he died, according to his wife Patricia, were Jason’s name.

On April 23rd, 2017, a local amateur geologist named Brian Collins was exploring a remote canyon about 35 mi southwest of Zabriski Point.

Collins was 52 years old and had spent most of his life studying the geological formations of Death Valley.

He was a member of the Southern California Amateur Geologist Society and regularly went on expeditions in search of interesting mineral and fossil specimens.

That day, Collins was walking through a narrow canyon with walls rising 25 ft on each side.

The canyon floor was strewn with sharp rocks and sparse creassote bushes.

The sun was high and the temperature was reaching 38°.

He stopped to drink some water from his canteen and his gaze fell on something unusual about 50 yards ahead.

The glint of metal in the sunlight.

Collins moved closer and saw a car half hidden behind a bend in the canyon.

A silver Toyota Camry covered in a thick layer of dust and sand.

The windshield was cracked but intact.

The hood was covered in dents, probably from falling rocks.

The tires were flat.

The rubber cracked from years of exposure to ultraviolet light and extreme temperatures.

Collins first thought was that it was an abandoned car, possibly stolen and left here decades ago.

Such finds were not uncommon in the desert.

But when he looked through the driver’s side window, his heart stopped.

Two skeletons were sitting in the front seats.

One was behind the wheel, the other in the passenger seat.

They were dressed in the rags of what had once been summer clothes.

The bones were clean, white, completely stripped of flesh.

The skulls were tilted back, the jaws open.

The driver’s hands were still on the steering wheel, as if the man had died, clinging to his last hope of salvation.

But the most shocking thing was what was growing through their bodies.

From the center of the cabin between the seats, rose a cactus, a young prickly pear about 4 feet tall with several broad green pads covered with sharp spines.

The cactus trunk passed right through the rib cages of both skeletons.

The roots of the plant went down, piercing the floor upholstery of the car, reaching the ground under the car.

The upper parts of the cactus grew upward, some pads resting against the roof of the passenger compartment, deforming the metal from the inside.

Collins stepped back from the car, feeling his stomach clench with horror.

He took out his cell phone.

There was no signal.

It took him 40 minutes to get out of the canyon and reach a place where he could get reception.

With trembling fingers, he dialed 911.

3 hours later, the sight of the discovery had turned into a hive of activity.

Police cars, National Park Service SUVs, a medical examiner’s van, all were parked at the edge of the canyon.

It was impossible to drive down due to the narrowness of the passage and the steepness of the slope.

Equipment and personnel were carried down by hand.

Detective Mark Rivera, who had led the investigation into the Harrison’s disappearance 13 years ago, was among those who arrived.

He was now 57 years old with gray hair and deep wrinkles around his eyes from decades of working under the California sun.

When he saw the license plate on the car, his heart beat faster.

He checked the database.

The number matched a Toyota Camry registered to Jason Harrison.

The chief medical examiner for Inyo County, Dr.

Sarah Chen, arrived with her team.

They set up a tent for shade and began documenting the site.

Photos from every angle, measurements, notes.

Everything had to be recorded before they touched anything.

Chen approached the car in protective clothing and gloves, although it was obvious that after 13 years in the desert, no pathogens could have survived.

She carefully examined the skeletons without touching them.

The bones were in surprisingly good condition considering the time and conditions.

The dry desert climate had acted as a natural mummification, preventing decay.

The strangest detail was the cactus.

Chen had never seen anything like it in her 23 years as a medical examiner.

The plant grew through the ribs of both skeletons, its roots intertwined with the bones, penetrating the chest cavity.

It did not look like a natural process where a seed accidentally sprouted next to the remains, but rather like a deliberate planting.

She called in a botonist from the University of Nevada, Dr.

Alan Graham, who specialized in desert flora.

Graham arrived the next day and conducted a detailed examination of the cactus.

His findings were disturbing.

The plant, Opuntia Basilica, was about 12 to 13 years old, judging by the size and number of pads.

This meant that it had been planted shortly after the deaths of the people in the car.

Graham also noted that the position of the plant was completely unnatural.

The cactus could not have grown on its own in such a configuration.

Someone had dug a hole through the car’s floor upholstery, planted a young plant or seed with roots, and positioned it precisely so that as it grew, it would pass through the chest cavities of the bodies.

This required time, planning, and a complete lack of human compassion.

Detective Rivera realized that he was dealing not just with a tragic death from dehydration, but with something more sinister.

Someone had found the Harrison’s body shortly after their death, and instead of calling for help, or at least notifying the authorities, had decided to turn them into part of some macabra art project.

He began by examining the traces.

Years had passed, but the desert preserves traces better than one might think.

In sheltered areas of the canyon under rock ledges, experts found tire tracks.

Not from a Toyota, these tracks belong to a larger vehicle, probably an SUV with wide tires for off-road driving.

Trace expert David Thompson made casts and photographs of the tread.

The pattern was distinctive, aggressive tread for extreme off-roading, BFG Goodrich brand, popular with off-road enthusiasts and hunters.

The size indicated a large pickup truck or full-size SUV.

Rivera requested a list of all owners of vehicles with such tires registered in the counties of Inyo, San Bernardino, and Southern Nevada.

The list included more than 300 names.

A way was needed to narrow down the circle of suspects.

He returned to his original theory.

If this was an art project, the perpetrator probably had an art education, or was known in the local art community.

Rivera began interviewing gallery owners, exhibition curators, and art teachers at colleges and universities in the region.

A week later, he got his first lead.

The owner of a small gallery in the town of Batty, Nevada, 25 miles from the California border, told him about a local artist named David Crane.

Crane was 59 years old, lived in an isolated house in the desert and created what he called death installations.

Crane, according to the gallery owner, worked with themes of mortality, decay, and the relationship between life and death.

His works often included animal bones found in the desert, dried plants, and elements of abandoned cars and buildings.

Several years ago, he offered to show her a series of photographs depicting animal remains surrounded by plants.

She declined, finding the works too dark and potentially offensive to visitors.

Rivera inquired about Crane.

He had an art education, a master’s degree in fine arts from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, obtained in the late 1980s.

After that, he taught at a local college for several years, but was dismissed after a series of complaints about the unacceptable content of his lectures.

Since the early 2000s, he had lived as a recluse, rarely appearing in town, earning a meager living by selling his art online.

More importantly, Crane owned a blue 2001 Ford F250 equipped with the very BFG Goodrich tires whose tracks were found in the canyon.

On April 29th, Rivera along with two officers from the NY County Sheriff’s Office in Nevada headed to David Crane’s house.

The house was located at the end of a dirt road 15 miles from the nearest highway.

The building was small, half buried in the hillside to protect it from the heat.

Surrounding it were various sculptures and installations, twisted metal, bleached bones, wooden structures entwined with dry branches.

A blue pickup truck stood next to the house, covered in dust.

Rivera knocked on the door.

There was no answer.

He knocked again, louder, shouting that he was the police.

A minute later, the door opened.

David Crane was a tall, thin man with long gray hair tied back in a ponytail.

His face was tanned and lined with wrinkles.

His eyes were gray, cold, and searching.

He was dressed in a faded denim shirt and worn khaki pants.

Rivera introduced himself and explained the purpose of his visit.

He wanted to ask a few questions about the discovery in the canyon.

Crane showed no surprise or concern.

He invited them in.

Inside the house was cluttered with artwork.

The paintings on the walls depicted desert landscapes populated by strange forms, skeletons, plants, abstract structures.

On the table were photographs of various installations in the desert.

Rivera recognized the distinctive style.

Bones entwined with plants, animal skulls with cacti growing out of their eye sockets, deer ribs formed into geometric patterns.

Rivera asked if Crane had been to the area where the car was found.

Crane replied that he had been to that canyon many times.

It was one of his favorite places to work.

Deserted, remote, perfect for his projects.

Had he been there in 2004? Crane thought about it.

Maybe he had been going there regularly every summer for 20 years.

He couldn’t remember the exact dates.

Rivera showed him a photo of a car with a cactus growing through the skeletons.

Had he seen it before? Crane took the photo and studied it for a long time.

Then he said yes.

It was his work, one of a series called Rebirth Through Death.

Rivera felt adrenaline rush through his veins.

He asked if Crane understood that these were not animal bones, but human remains.

Crane nodded.

He knew he had found the car with the dead people inside in the summer of 2004, about a week after they had been there, judging by the condition of the bodies.

Why didn’t he report it to the police? Crane shrugged.

They were already dead.

Nothing could be done for them.

But he could do something meaningful with their deaths.

Turn them into art.

Into a commentary on the cycle of life, on how death nourishes new life.

Rivera asked him to describe the process.

Crane explained without emotion.

He returned the next day with tools and a young cactus.

He cut a hole in the floor of the car and planted the plant so that it would grow through the bodies.

It took several hours of work.

He took photographs documenting the initial stage, planning to return years later to see how the work had developed.

Officers arrested Crane on charges of concealing a death, desecrating human remains, and obstructing justice.

During a search of his home, they found a hard drive with hundreds of photos of his work.

Among them were images of six other installations involving human remains.

Over the next 2 weeks, teams of police and forensic experts combed the desert using GPS coordinates from Crane’s photo metadata.

They found the remaining six sites.

The first site was located 30 mi north of the initial discovery.

Here, the skeleton of a young man lay at the foot of a rock, his arms spread out to the sides.

Two yucka plants grew out of the eye sockets of the skull, their roots piercing the skull.

Dental records identified the remains as Mark Jenkins, a 22-year-old student from Utah who disappeared during a solo hike in 2006.

The second site was in an abandoned mine.

Three skeletons sat around a table made of old planks.

Rusty tin cans and bottles stood on the table.

A Joshua tree grew out of each skeleton’s rib cage, its roots reaching deep into the mine.

Identification was difficult due to the lack of dental records, but one of the skeletons probably belonged to a man who disappeared in the 1990s.

The third, fourth, and fifth locations contained the remains of tourists and travelers who disappeared in various years between 2000 and 2015.

Each time, Crane found the bodies of people who had died of dehydration, accidents, or medical problems in remote parts of the desert and turned them into his Macob works of art.

The sixth site was the most disturbing.

In a narrow gorge lay the remains of a mother and her young child.

The woman, according to identification, was Maria Sanchez, a 34year-old nurse from Arizona who disappeared with her 5-year-old daughter Isabelle in 2012 while on vacation.

Crane joined their skeletons in an embrace and planted a flowering yucka so that the plant would entwin them both.

Photographs showed how over the years the plant grew, creating a crown of white flowers above their remains.

Each site was carefully documented.

Crane kept records of each installation, the date of creation, the plants used, his thoughts and interpretation of the work.

For him, it was not a crime.

It was art.

He saw himself as a mediator between death and life, creating something beautiful out of tragedy.

David Crane’s trial began in October 2017 in the County Court of Ino.

The prosecution brought seven counts of obstruction of justice, seven counts of desecration of human remains, and additional charges of concealing deaths.

The defense attempted to portray Crane as an eccentric artist whose actions, while unorthodox, were not motivated by malice.

His lawyer argued that Crane did not kill these people.

He simply found them already dead and attempted to create something meaningful.

In a way, he even immortalized their memory through his art.

The prosecutor, Assistant District Attorney Jennifer Lopez, vehemently objected.

She presented testimony from the victim’s families who had suffered for years without knowing what had happened to their loved ones.

If Crane had reported his first discovery in 2004, the Harrison’s parents could have had closure 13 years earlier.

Robert Harrison could have died knowing the truth rather than in the agony of uncertainty.

She also presented psychological evaluations conducted by three independent psychiatrists.

All three concluded that Crane suffered from a severe personality disorder with narcissistic and antisocial traits.

His inability to feel empathy and his view of human remains as mere material for art indicated a deep pathology.

The key moment of the trial was Crane’s own testimony.

He expressed no remorse.

He insisted that his works had artistic value.

He spoke about the philosophy of his art, about the cycles of nature, about the beauty of decay and rebirth.

When asked if he felt anything for the victim’s families, he replied that he understood their grief, but that it did not change the significance of his work.

This cold, calculated response stuck in the minds of the jury.

It took them only 3 hours of deliberation to reach a verdict.

Guilty on all counts.

Judge Margaret Evans handed down a sentence of 52 years in prison without the possibility of parole.

Given Crane’s age, this was effectively a life sentence.

In delivering the sentence, the judge said that although Crane had not killed his victims, his actions had deprived their families of the opportunity to bury their loved ones with dignity and had prolonged their suffering for years.

This deserved the most severe punishment available under the law.

What do you think about this case? Can the use of human tragedies for art ever be justified? And how should we treat those who see beauty where others see only horror? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

News

Six Cousins Vanished in a West Texas Canyon in 1996 — 29 Years Later the FBI Found the Evidence

In the summer of 1996, six cousins ventured into the vast canyons of West Texas. They were last seen at…

Sisters Vanished on Family Picnic—11 Years Later, Treasure Hunter Finds Clues Near Ancient Oak

At the height of a gentle North Carolina summer the Morrison family’s annual getaway had unfolded just like the many…

Seven Kids Vanished from Texas Campfire in 2006 — What FBI Found Shocked Everyone

In the summer of 2006, a thunderstorm tore through a rural Texas campground. And when the storm cleared, seven children…

Family Vanished from Stillwater Lake Texas in 1995 — 27 Years Later FBI Found Box with Clothes

In the summer of 1995, the Whitlock family vanished without a trace during their weekend retreat at Stillwater Lake. Their…

Family Vanished from Stillwater Lake Texas in 1995 — 27 Years Later FBI Found Box with Clothes

In the summer of 1995, the Whitlock family vanished without a trace during their weekend retreat at Stillwater Lake. Their…

SOLVED: Arizona Cold Case | Robert Williams, 9 Months Old | Missing Boy Found Alive After 54 Years

54 years ago, a 9-month-old baby boy vanished from a quiet neighborhood in Arizona, disappearing without a trace, leaving his…

End of content

No more pages to load