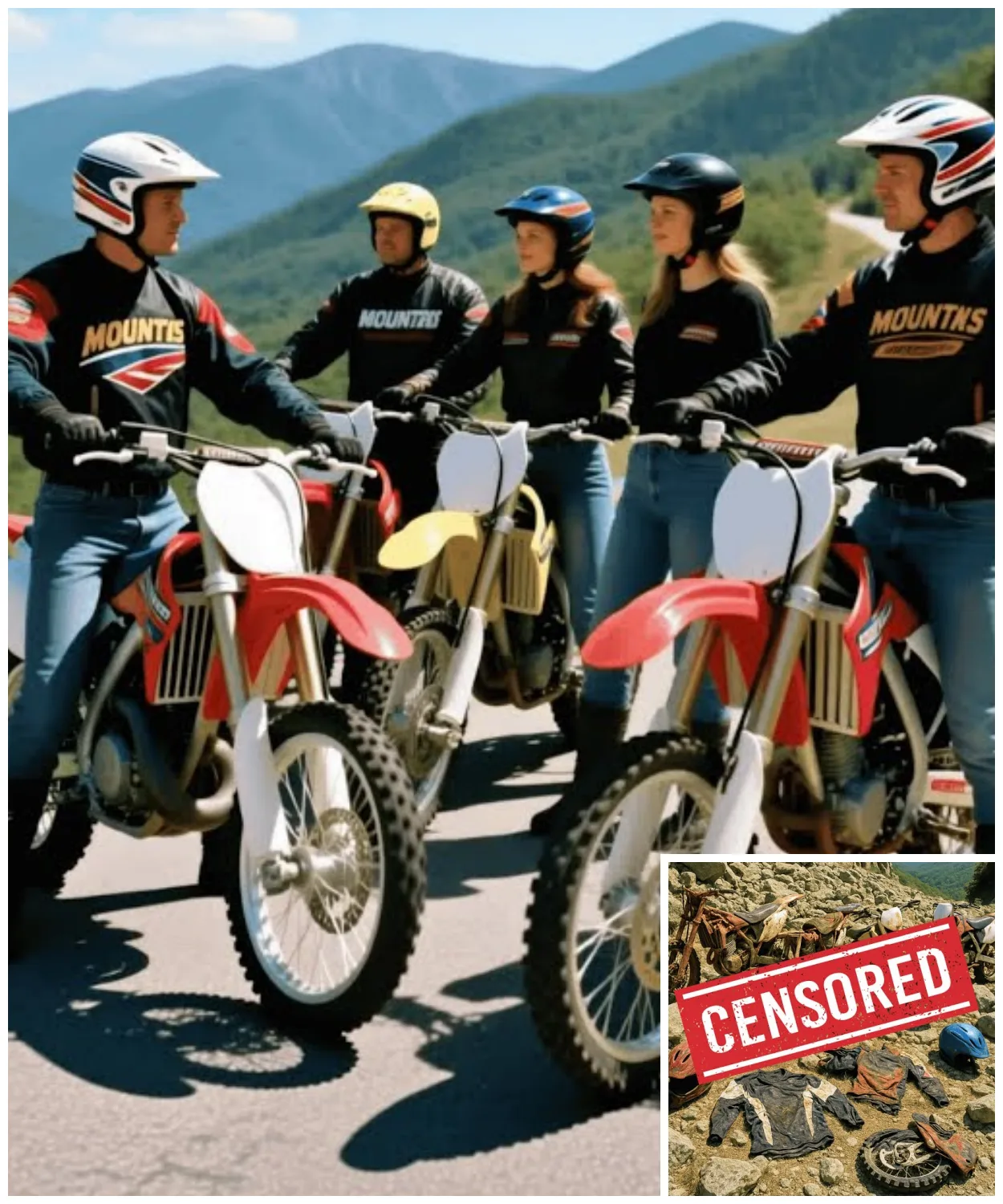

In August 1998, five experienced bikers rode into North Carolina’s Pisca National Forest and simply disappeared.

For 13 years, search teams found nothing.

No trace, no answers, no closure for the families left behind.

Then in 2011, a routine geological survey stumbled upon something that changed everything.

What investigators discovered raised more questions than it answered.

Why were the bikes arranged that way? What explained the condition of the gear they found scattered across that remote ridge? And most disturbing of all, why did forensic analysis suggest the group had survived for days after vanishing? Before I continue, I would love to hear where you are from.

Drop it in the comments below and subscribe to the channel to stay part of this community.

They weren’t weekend warriors playing at Adventure.

These five had logged hundreds of trail miles together across three states.

Jason, at 34, worked as a mechanical engineer in Charlotte and had been riding mountain trails since his college days.

Eric, 31, taught high school biology and spent every summer break exploring new routes.

Chad, the youngest at 28, operated a small outdoor equipment shop in Asheville.

Amanda, 32, was a physical therapist who’d competed in amateur cross-country races.

Tiffany, 29, worked as a freelance photographer and documented their trips.

They’d planned this particular expedition for 6 months, mapping routes through some of the most remote sections of Pisca National Forest.

What none of them knew was that this trip would be their last.

The group had selected a challenging 70-mi route through the remote southern section of Pisca National Forest, an area known for steep elevation changes and technical terrain.

They planned to complete the circuit over 4 days, camping at designated sites along the way.

Jason kept meticulous records of their route plan, which he filed with the local ranger station on August 14th, 1998.

The document listed their intended campsites, expected daily mileage, and estimated return date of August 18th.

Each rider carried standard safety equipment, including first aid kits, emergency beacons, and enough food for 5 days.

They had satellite phones which were relatively new technology at the time.

The weather forecast looked favorable with clear skies and temperatures in the mid70s.

Every precaution seemed covered, but sometimes preparation means nothing against what waits in the wilderness.

On the morning of August 14th, the group met at the Davidson River Campground at .

Park Ranger Michael Chen checked their permits and noted their departure in his log.

He would later recall that the group seemed wellprepared and in good spirits.

Jason went over the route one final time with everyone gathered around a topographic map spread across a picnic table.

They divided supplies among their packs, ensuring weight distribution remained balanced.

By , they began pedalling up Forest Road 475, heading toward their first trail junction.

Three other campers saw them pass and waved.

A couple from Georgia, Thomas and Linda Hayes, even took a photograph of the group as they rode by, bikes loaded with gear, helmets gleaming in the early morning sun.

That photograph would become crucial evidence later, the last confirmed image of the five alive.

The first day’s route covered 18 mi through moderately difficult terrain, climbing from 2,000 ft elevation to just over 4,000 ft.

According to their plan, they intended to camp near Butter Gap, a scenic overlook popular with experienced hikers.

The trail followed old logging roads for several miles before narrowing into single track paths through dense ruddendron thicket.

Other trail users reported seeing the group at various points that first day.

A solo hiker named Robert Patterson encountered them around noon near the Looking Glass Rock Trail intersection.

He chatted briefly with Eric about water sources ahead.

A group of three-day hikers saw them again around in the afternoon.

Ascending toward Buttergap, everything appeared normal.

The bikers seemed tired but happy, exactly as you’d expect on the first day of a challenging route.

No one reported anything unusual or concerning.

Jason had arranged to call his wife Karen each evening around using their satellite phone.

These devices were expensive and somewhat unreliable in 1998, especially in areas with heavy tree cover, but they represented the best available technology for backcountry communication.

Karen received Jason’s call that first evening right on schedule.

He reported that everyone felt good, the weather remained perfect, and they’d reached Buttergap without incident.

The conversation lasted about 5 minutes.

Karen would later tell investigators that Jason sounded relaxed and mentioned they were setting up tents while Eric started a fire for dinner.

He said they’d covered good distance and felt optimistic about staying on schedule.

They exchanged brief personal news, and Jason ended the call, saying he’d talk to her the next night.

That was the last time Karen heard her husband’s voice.

The second day’s route represented the most challenging section of their entire trip.

They planned to cover only 12 mi, but those miles included several brutal climbs and technical descents through the Black Balsom area.

This section of trail required riders to carry bikes over several rocky outcroppings too steep and loose to ride.

Even experienced mountain bikers consider this terrain demanding.

The group broke camp early according to plan, probably around based on typical patterns.

No other trail users reported seeing them that day, which wasn’t surprising given how remote that particular section was.

The trails through Black Balsom Sea, relatively light traffic, even during peak season.

Most recreational riders avoid the area because of its difficulty.

But for experienced riders like Jason’s group, this represented exactly the kind of challenge they sought.

The isolation that made the area appealing would soon become a critical problem.

When came and went on August 15th without a call from Jason, Karen wasn’t immediately worried.

She knew satellite phones failed regularly in mountainous terrain and the group was traveling through some of the most remote country in the eastern United States.

She waited until , then tried calling Jason’s satellite phone.

The call wouldn’t connect.

She tried three more times before going to bed, telling herself that technical difficulties explained the silence.

But by the next morning, when no call came and her attempts to reach Jason continued failing, real worry began setting in.

She called Eric’s girlfriend, Michelle Torres, who hadn’t expected a call, but confirmed she couldn’t reach Eric either.

By noon on August 16th, both women agreed something felt wrong.

Karen called the ranger station at Pisca National Forest at that afternoon.

What she set in motion would become one of the largest search operations in North Carolina history.

Ranger Michael Chen, the same ranger who’d checked their permits, received Karen’s call.

He pulled the wrote plan Jason had filed and studied it carefully.

The group was now 2 days into a 4-day trip traveling through extremely remote territory.

Chen knew that missed satellite phone calls weren’t necessarily cause for alarm, but his experience told him not to dismiss the concern.

He consulted with District Ranger Patricia Wells, and they decided to initiate a preliminary search that afternoon.

Chen and two other rangers hiked to Buttergap, where the group had camped the first night.

They found the campsite quickly.

The fire ring showed recent use, and the ground around it bore clear evidence of five tents, but everything had been packed up and removed.

The site looked exactly as it should, clean, properly managed, following leave no trace principles.

The rangers found nothing concerning at all.

If anything, the neat condition of the campsite, suggested an experienced, careful group.

By August 17th, when the group failed to arrive at their second planned campsite, and still hadn’t made contact, Ranger Wells escalated the search.

She contacted the North Carolina Search and Rescue Council and by late afternoon 23 volunteers joined park service personnel in the effort.

The search coordinator, Daniel Murphy, had 30 years of experience in mountain rescue operations.

He divided teams to cover the group’s planned route and several alternate paths they might have taken if conditions required changes.

Search teams included experienced trackers and several members brought search dogs.

The operation focused on the section between Butter Gap and the Black Balsom area, roughly 15 square miles of heavily forested mountainous terrain.

Teams hiked every major trail and many minor paths.

They called out constantly, blew whistles, and listened for any response.

By nightfall, they’d covered the primary route without finding any sign of the missing bikers.

Murphy expanded the search grid for the following day.

Karen Weter arrived in the area on August 18th, driving through the night from Charlotte.

Amanda’s parents, Robert and Susan Keller, came from Virginia.

Eric’s girlfriend, Michelle, arrived with his brother, David Dawson.

Chad’s father, William Reynolds, flew in from Ohio.

Tiffany’s sister, Nicole Morals, drove from South Carolina.

The families gathered at the Ranger Station, desperate for information and struggling with fear that grew with each passing hour.

Ranger Wells briefed them on search efforts and showed them maps marking areas already covered.

She emphasized that the terrain was vast and complex with countless places where a group might be delayed or stuck without necessarily being in danger.

The families clung to these reassurances, but the room felt heavy with unspoken dread.

Karen kept staring at the map, trying to will some insight about where Jason might be.

The satellite phone should work somewhere.

Why hadn’t they heard anything? By August 19th, the search operation involved 75 personnel, including park rangers, volunteer search and rescue teams, and local law enforcement.

A helicopter from the North Carolina Highway Patrol joined the effort, flying grid patterns over the planned route and surrounding areas.

The aerial search revealed just how dense and vast the forest was.

From above, the tree canopy created an almost unbroken green blanket.

Finding five people and their bikes in that landscape seemed nearly impossible.

Ground teams pushed deeper into remote areas, following every trail junction and checking every possible campsite.

They found plenty of evidence of other recent camping activity, but nothing they could definitively connect to Jason’s group.

The search dogs showed interest in several locations, but trails ended at rocky outcroppings where scent couldn’t travel.

Daniel Murphy told the families that weather conditions remained stable, and that gave him hope.

If the group was injured or trapped somehow, at least they weren’t dealing with exposure.

As days passed, with no discoveries, searchers and families began developing theories about what might have happened.

The most optimistic scenario suggested the group had simply gotten lost or taken a wrong turn, ending up in a remote area outside the search grid.

Mountain bikers can cover surprising distances, and if they’d misread the map, they might be many miles from their intended route.

A darker possibility involved injury.

If one or more riders had suffered serious trauma from a fall, the others might have stayed with them, unable to move and beyond cell or satellite coverage.

Some searchers privately wondered about animal encounters.

Black bears inhabit Pisca National Forest, though attacks on humans are extremely rare.

A few mentioned that the area has steep cliffs and hidden ravines where a rider could fall and become invisible from even a few feet away.

Karen refused to consider the worst possibilities.

She focused on the practical question that haunted everyone.

Why hadn’t anyone found a single piece of equipment, a tire track, anything? Expert trackers brought in from Tennessee specifically examined the trail section beyond Butter Gap toward Black Balsam.

Larry Foster had tracked missing persons for 23 years and had an exceptional success rate finding lost hikers.

He studied the trail carefully, looking for any sign that bikes had passed through recently.

In several locations, he found marks in the dirt that could have been tire tracks, but weather and other trail traffic made definitive identification impossible.

At one rocky section called Devil’s Elbow, where riders would need to carry bikes, Foster found scuff marks on stones that looked fresh.

But again, he couldn’t say with certainty they came from Jason’s group.

The trail forked in three places where riders might have made navigation errors.

Search teams thoroughly explored each alternate path.

They found campsites, but none showed recent use.

The forest seemed to have swallowed five people and their bikes without leaving a trace.

Foster told Daniel Murphy he’d never encountered anything quite like it.

By August 21st, news outlets across North Carolina were covering the story.

Television crews set up at the Ranger Station, interviewing family members and showing footage of search operations.

The Asheville Citizen Times ran daily front page updates.

The story spread to regional and then national news.

Five mountain bikers vanish in Piskah Forest became a headline that captured public imagination.

The families appreciated the attention, hoping it might generate leads.

Ranger Wells organized a press conference where she displayed large maps showing the search area and explained the challenges involved.

Reporters asked difficult questions.

Had foul play been considered? Could the group have been kidnapped? Wells stated firmly that nothing suggested criminal activity and the investigation remained a search and rescue operation.

Still, law enforcement began examining other possibilities.

Special Agent Frank Morrison from the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation quietly joined the effort, reviewing the case from an investigative rather than purely searchoriented perspective.

Agent Morrison and his team conducted thorough background investigations on all five missing persons.

They looked for anything that might suggest reasons someone would want to disappear.

Jason’s financial records showed no unusual transactions or debts.

His marriage appeared stable and co-workers described him as reliable and content.

Eric had recently received a teaching award and was planning to propose to Michelle at Christmas.

Chad’s business was struggling slightly, but nothing catastrophic, and he’d just signed a lease on a larger retail space.

Amanda had a thriving physical therapy practice and was saving to buy a house.

Tiffany had recently sold several photographs to a national magazine, and her career was gaining momentum.

None of the five had criminal records beyond minor traffic violations.

Their friends universally described them as responsible, safetyconscious people who loved outdoor adventure.

Morrison found absolutely nothing suggesting any of them wanted to vanish or had enemies who might wish them harm.

The investigation reinforced the most troubling conclusion.

Something had happened to them in the wilderness.

By midepptember, the intensive search phase scaled back.

Hundreds of volunteer hours had been logged.

Every mile of the planned route had been covered multiple times.

Searchers had expanded far beyond the original grid, covering over 200 square miles of wilderness.

They’d found nothing.

The families remained in the area, many taking time off work to personally join search efforts.

Karen hiked trails daily with volunteer groups, calling Jason’s name until her voice went.

The Ranger Station became a makeshift headquarters where family members gathered each morning to review search plans, psychological toll-mounted.

The uncertainty felt worse than definitive bad news.

At least closure would allow grief to begin processing.

This indefinite state of not knowing created a special kind of agony.

Robert and Susan Keller celebrated their daughter Amanda’s 33rd birthday on September 19th by hiking to Buttergap, the last place they knew she’d been confirmed.

They sat at the campsite and wept.

As October arrived, weather began limiting search operations.

The first hard frost came early that year.

Ranger Wells explained to families that winter conditions would make continued searching dangerous for volunteers and likely futile.

Snow would soon cover any remaining evidence.

The case remained open and rangers would check the area during winter patrols, but organized search operations ceased.

The decision devastated the families, though they understood the reality.

Karen returned to Charlotte, but found normal life impossible.

She took extended leave from her job as an accountant.

The house she’d shared with Jason felt like a museum of grief.

His mountain bike hung in the garage exactly where he’d left it.

His coffee mug still sat on the kitchen counter.

Michelle Torres struggled similarly.

She’d planned to say yes when Eric proposed.

Now she faced holidays alone, haunted by might of the five families stayed in close contact, bound by shared tragedy and the terrible question that wouldn’t leave them alone.

What happened in those mountains? When August 1999 arrived, marking one year since the disappearance, the families organized a memorial service at Davidson River Campground.

Over 200 people attended, including many volunteers who’d participated in search operations.

Five empty chairs sat at the front, each draped with clothing the missing person had been wearing, Jason’s Charlotte Hornets cap, Eric’s Duke University t-shirt, Chad’s flannel shirt, Amanda’s running jacket, Tiffany’s camera strap.

People shared memories and stories.

Jason’s co-workers talked about his infectious laugh and brilliant problem solving skills.

Eric’s students described how he made biology come alive.

Chad’s customers remembered his encyclopedic knowledge of outdoor gear.

Amanda’s patients spoke of her gentle encouragement during difficult recovery periods.

Tiffany’s photography colleagues showed some of her best work.

Karen Whitaker stood and addressed the gathering.

She thanked everyone for support, acknowledged the pain of not knowing, but insisted they couldn’t give up hope.

Maybe someday, somehow, answers would come.

Between 1999 and 2011, the case gradually faded from public attention.

The families never stopped searching for answers, but organized efforts had ended.

Karen Whitaker became an advocate for improved wilderness safety regulations.

She worked with legislators to require more robust emergency communication systems in national forests.

Eric’s brother David periodically returned to Piskah Forest, hiking sections of the route and posting updates on a website he maintained about the disappearance.

The site attracted attention from amateur sleuths and armchair detectives who proposed various theories, most far-fetched, about what might have happened.

Some suggested the group had deliberately vanished to start new lives.

Others speculated about secret military operations in the area.

A few claimed alien abduction.

These wild theories hurt the families, trivializing real loss.

Most years, local newspapers ran anniversary stories marking another year without answers.

Ranger Patricia Wells, who’ coordinated the initial search, never forgot the case.

It haunted her throughout her career.

In June 2011, the United States Geological Survey contracted with a private firm to conduct mineral and geological assessments in several areas of Peas National Forest.

The work involved creating detailed topographical maps using new laser scanning technology.

Graduate student Tim Bradford was part of a four-person team working in the Black Balsam region.

On June 7th, the team was mapping a particularly remote section when their equipment readings showed unusual anomalies in a narrow ravine about a half mile off any established trail.

The ravine was steep-sided and heavily overgrown with mountain laurel and roodendron.

Tim’s supervisor, Dr.

Helen Chang, decided they should physically investigate the anomalies rather than just note them.

The team bushwacked through dense vegetation toward the ravine.

As they got closer, Tim saw something orange partially visible through the undergrowth.

He pushed branches aside and froze.

He was looking at a rusted, deteriorated mountain bike lying against a rock.

His heart started racing.

This was clearly very old, but something about it felt significant.

Dr.

Chang and the team carefully approached the area where Tim had spotted the bike.

As they moved vegetation aside, more objects became visible.

Another bike, also heavily rusted and damaged, lay 10 ft away.

Then another, then two more.

Five mountain bikes in total, arranged in a rough semicircle in a small clearing at the bottom of the ravine.

The clearing measured maybe 20 ft across, surrounded on three sides by rock walls 30 to 40 ft high.

Dense vegetation created a natural roof overhead.

You could walk within 15 ft of this spot and never know it existed.

The bikes were in terrible condition after 13 years of exposure to weather.

Rustco covered metal components.

Tires had rotted away, but the bikes were clearly highquality mountain bikes, exactly the type serious riders would use.

scattered around the bikes.

The team found other objects, deteriorated backpacks, pieces of camping equipment, a rusted camp stove, and something else that made Dr.

Chang immediately pull out her satellite phone to call authorities.

Clothing, definitely human clothing.

Chang reached the Transennsylvania County Sheriff’s Department at that afternoon.

She reported finding what appeared to be an old campsite with multiple bicycles and personal effects in an extremely remote location.

She emphasized that the scene felt unusual, possibly significant.

Deputy Sheriff Marcus Williams took down the GPS coordinates and said officers would respond immediately.

Doctor Chang ordered her team to leave the area without touching anything else.

They retreated about 50 yards and waited.

The location’s remoteness meant it took responding officers nearly 3 hours to reach the site, even knowing exact coordinates.

Sheriff Raymond Foster arrived with three deputies and a medical examiner just before .

The evening light was fading fast.

Foster surveyed the scene and immediately recognized they were looking at something important.

He’d been a deputy back in 1998 when five mountain bikers vanished.

Everyone in local law enforcement remembered that case.

The cold feeling in his stomach told him they just found those bikers last campsite.

But where were the bikers themselves? Sheriff Foster declared the site a potential crime scene and ordered it secured.

Deputies strung yellow tape around a wide perimeter.

They brought in portable lights as darkness fell.

Foster called Ranger Patricia Wells, now the district’s head ranger, and told her they’d found something significant in the Black Balsom area.

He read coordinates.

Wells pulled up the old case file and compared the location to the 1998 search grid.

The ravine sat approximately 800 ft off the planned road, just beyond where searchers had looked.

The terrain made sense for why it was missed.

The ravine was invisible from above and from the surrounding trails.

Wells said she’d arrive first thing in the morning.

Foster ordered his deputies to guard the site overnight and called for a full investigative team at sunrise.

He stood in the portable lights staring at those five bikes arranged in their semicircle and felt felt certain he was looking at something terrible.

The arrangement looked intentional somehow, though he couldn’t articulate why.

Nothing about this scene suggested accident or misadventure.

Before dawn on June 8th, Sheriff Foster made the hardest calls of his career.

He reached Karen Whitaker first.

He explained carefully that a geological team had discovered what appeared to be a campsite with five mountain bikes and equipment in Pisgah National Forest.

He said the location matched the area where her husband’s group had been traveling in 1998.

Karen’s first question was whether they’d found bodies.

Foster said no, not yet.

But he wanted to prepare her that the investigation was now active again.

Karen thanked him, hung up, and collapsed on her kitchen floor, sobbing.

For 13 years, she’d lived in terrible limbo.

Now something had been found and the not knowing was somehow becoming even worse.

Foster called the other families with similar messages.

By midm morning, all of them were making arrangements to travel to North Carolina.

They had been through this agony before in 1998.

This time felt different.

This time there was actual evidence.

Something had been found.

But what did it mean? Where were their loved ones? At first light on June 8th, a team of 12 investigators descended into the ravine.

They included Sheriff Fosters deputies, FBI special agent Rebecca Torres, who specialized in missing person’s cases, State Bureau of Investigation agents, and forensic specialists.

They worked slowly photographing everything before touching anything.

The scene showed extensive weather damage after 13 years of exposure, but certain facts became clear quickly.

The five bikes, while rusted and deteriorated, could still be identified by serial numbers on the frames.

By late morning, they’d confirmed these were the exact bikes registered to Jason Whed, Eric Dawson, Chad Reynolds, Amanda Keller, and Tiffany Moral.

The backpacks contained items consistent with what the missing group had been carrying camping gear, clothing, water bottles.

One particularly significant find was a rusted but still somewhat intact satellite phone.

It was registered to Jason Wetaker.

The discovery that would haunt investigators was the arrangement.

Everything looked deliberately placed, organized almost ceremonially.

This was no accident scene.

Forensic teams worked the site for three days documenting and collecting every item.

They found no human remains, which struck everyone as profoundly strange.

If the bikers had died at this location, where were they? The clothing found at the scene included five helmets, five pairs of riding gloves, and five sets of cycling shoes, plus various other garments.

Forensic anthropologist Dr.

Sarah Martinez examined every piece carefully.

Some clothing showed tears and damage beyond simple weather degradation.

One jacket had what appeared to be claw marks, deep goes through the tough fabric.

A pair of pants showed similar damage.

Doctor Martinez was cautious about interpretation, but the marks suggested animal activity.

However, the pattern seemed wrong for scavenging after death.

These marks looked like defensive wounds made while someone wore the clothing.

More disturbing, several items showed dark staining that field testing suggested might be human blood.

Samples went to the lab for confirmation and DNA analysis.

The results would take weeks.

Investigators found something unexpected among the deteriorated equipment.

Two rusted metal waterproof containers designed for protecting documents and electronics.

One container held a thoroughly degraded digital camera that forensic teams hoped might yield some data.

The other contained water damaged notebooks.

Tiffany moral had been known for keeping detailed journals of their trips and Amanda Keller also journaled regularly.

The notebooks were in terrible condition, pages fused together by 13 years of moisture.

Forensic document experts at the FBI laboratory in Quantico carefully separated pages using specialized techniques.

Many pages were completely illeible.

Ink dissolved into muddy smears, but some portions remained readable, offering fragments of what happened after the group reached this ravine.

The process of reconstructing these journals would take months, but early indications suggested the group had survived in the ravine for some time after arriving.

The question was how long and what had happened during that time.

Special Agent Rebecca Torres led the effort to reconstruct a timeline.

Jason Wetaker’s last confirmed phone call to his wife occurred at on the evening of August 14th, 1998.

He reported the group was at Buttergap on schedule, everyone fine.

No contact occurred after that.

Search teams found the campsite at Buttergap, showing the group had indeed camped there the first night.

The route plan showed they should have traveled toward Black Balsam on August 15th.

The ravine where evidence was found sat roughly at the midpoint of that day’s planned route.

This suggested the group reached the ravine on August 15th.

But here the timeline became deeply puzzling.

Some items found at the scene, specifically a calendar torn from a notebook and certain journal entries that were partially readable, suggested the group remained at the ravine for an extended period.

Forensic analysis of plant growth patterns around the bikes and equipment supported this theory.

The question haunting Torres was simple but terrible.

If they survived in that ravine for days or weeks, why didn’t they leave? To understand what happened, investigators needed to comprehend the ravine itself.

They brought in a climbing team to thoroughly survey the site.

The ravine measured approximately 200 ft long, 20 to 30 ft wide at the bottom with walls ranging from 30 to 50 ft high on three sides.

The fourth side, where the geological team had entered, was heavily overgrown, but theoretically passable.

A small spring fed a trickle of water through the bottom, which explained why the site had water.

The rock walls were steep, but not technical climbing obstacles.

Someone with basic outdoor skills could climb them, especially with equipment.

Jason’s group had climbing rope among their gear.

So why hadn’t they climbed out? The vegetation overhead created a natural canopy that made the ravine nearly invisible from above.

Even the 1998 helicopter searches had missed it.

But being invisible from above didn’t explain why the group hadn’t simply walked out the way the geological team had entered, unless something prevented them from leaving.

In late July 2011, FBI document specialists completed initial analysis of the recovered journals.

Agent Torres received the report and immediately called Sheriff Foster.

They’d recovered enough text to piece together parts of what happened.

The earliest legible entry written in Tiffany’s handwriting was dated August 15th, 1998.

It read, “Found shelter in ravine after Eric’s accident.

His leg definitely broken, bone visible.

We can’t move him safely.” Jason trying satellite phone, but no signal in here.

Walls too high, trees too dense.

Chad and I tried climbing out the west wall, but rock too loose, dangerous.

Need to wait for rescue.

Set up camp, making Eric comfortable.

Amanda thinks we can get him stable.

We have food for several days.

Search teams will find us soon.

The matter of fact, Tone suggested the group initially viewed the situation as inconvenient but manageable.

They expected rescue.

That made what came next even more heartbreaking.

Because rescue never came, investigators pieced together what likely happened on August 15th.

The group was navigating the challenging terrain between Buttergap and Black Balsam when Eric Dawson suffered a serious accident based on journal entries and physical evidence.

He apparently struck a rock at high speed while riding down a steep section, went over his handlebars, and landed badly.

The compound fracture in his lower leg left bone exposed.

In 1998, wilderness medical protocol for this type of injury was clear.

Don’t move the patient without proper stabilization equipment.

The group made a judgment call to find shelter immediately rather than risk moving Eric over rough terrain.

They spotted the ravine and carried him down.

It seemed like a reasonable decision at the time.

Shelter from weather, water source, flat ground.

They expected to call for help using Jason’s satellite phone, but the ravine’s geography blocked the signal.

They expected to send someone out for help, but moving Eric seemed too risky, and splitting up in the wilderness violated basic safety protocol.

They expected search teams to find them.

That expectation would prove tragically wrong.

Another partially legible journal entry, dated August 16th, showed the group’s optimism fading.

Amanda’s handwriting noted Eric’s condition stable but painful.

Gave him most of our pain medication.

His fever concerns me, but that’s expected with compound fracture.

Jason climbed the south wall today.

Got high enough to see out.

Tried satellite phone from there, but still no signal.

Thinks the trees are still too dense even at that elevation.

We discussed sending someone out to get help but decided against it.

The terrain where we came in is extremely difficult.

One person alone could get injured easily.

Eric doesn’t want anyone taking that risk.

Says we should wait one more day.

Search teams must be looking for us by now.

We’re only about half a mile off road.

They’ll find us soon.

The faith that rescue was imminent appears in every early entry.

They had no way of knowing that searchers were looking in slightly different areas.

The ravine’s invisibility doomed them from the start.

This answers the first open loop question.

Why were the bikes arranged that way? Further journal entries dated approximately August 23rd revealed something that made investigators blood run cold.

Chad had written, “We arranged the bikes in a circle this morning.

Trying to create something visible from above.

If helicopters search the area, maybe they’ll see the pattern.

Reflected sun off the metal might catch someone’s eye.” We used all our brightest clothing to spread it out on rocks.

We keep hearing helicopters in the distance, but they never come close enough.

Jason keeps saying they’re probably following our planned route, which we left when Eric got hurt.

We made a terrible mistake coming down here.

Eric’s condition is worse.

Amanda does what she can, but we have no antibiotics.

We’re rationing food now.

been here nine days.

Where are the search teams? The bikes weren’t found arranged in a circle.

They’d been moved over 13 years by weather and landslides.

But the intent was clear, a desperate signal to searchers who never came close enough.

By the end of August 1998, based on recovered entries, the group faced a dire situation.

They’d brought food for 4 days with small emergency reserves.

After 2 weeks in the ravine, they were running out.

Journal entries described attempts to supplement supplies.

Chad wrote about finding wild berries growing on the ravine walls.

Tiffany documented trying to catch fish from the small stream, though it was too shallow and slow for significant fish populations.

They boiled water carefully, worried about jardia and other waterbornne parasites.

Eric’s condition dominated concerns.

His fever spiked despite Amanda’s efforts.

The wound showed signs of infection.

Without antibiotics, they could only clean it repeatedly and hope.

The group faced a terrible choice.

Stay together and hope for rescue or send people out for help despite risks.

Jason’s leadership appeared in multiple entries.

He kept spirits up, organized daily tasks, maintained watch schedules, hoping to signal any passing helicopters.

But the helicopters came less frequently as search operations scaled back after the first intensive week.

A journal entry dated approximately September 2nd contained the most difficult words investigators read.

Jason had written made the decision today.

Chad and I will leave at first light tomorrow.

Head back toward the main trail and bring help.

Amanda stays with Eric.

Tiffany stays to help Amanda.

We debated this for days, but Eric’s infection is critical.

He’s delirious with fever.

We’re out of food.

We’ve been here 19 days.

Something went wrong with the search.

We should have been found by now.

We have to get help ourselves.

Chad and I will carry minimal gear.

Move fast.

We can make it to the ranger station in 2 days.

If we push hard, then bring rescue team back.

Amanda cried when we decided.

She knows staying means another several days without food.

Tiffany pointed out we have water, which is most important for Eric.

We’ll make this work.

Tomorrow we start.

Eric needs hospital care immediately or he’ll die.

It was a sound plan.

Logical.

It might have worked, but something went catastrophically wrong.

Multiple journal entries from early September were completely illegible except for fragments.

What investigators could piece together suggested Jason and Chad left the ravine on September 3rd.

Amanda and Tiffany remained with Eric.

The next readable entry in Amanda’s handwriting was dated September 7th and consisted of just a few terrible lines.

Jason and Chad should have been back with help by now.

It’s been 4 days.

Something happened to them.

Eric died this morning at about 8.

His infection overwhelmed him.

Tiffany and I buried him as best we could.

We piled rocks over his body.

We’re alone now.

No food for 3 days.

We need to leave, find help ourselves, but scared of what happened to Jason and Chad.

Why haven’t they returned? The answer to that question would emerge slowly from evidence found at the scene.

Jason and Chad had never made it out of the ravine.

Something had stopped them, and that something explained what happened to all five bikers.

Forensic teams made disturbing discoveries throughout the ravine that hadn’t been immediately obvious during initial investigation.

About 100 ft from the main campsite, investigators found more deteriorated equipment, a climbing rope, two backpacks, and significantly two helmets showing major damage.

Deep dents and cracks marked both helmets.

Nearby rocks showed staining that tested positive for human blood.

Fabric fragments caught on rocks matched clothing known to belong to Jason and Chad.

Dr.

Martinez, the forensic anthropologist, carefully examined the area and delivered a grim assessment to agent Tories.

This was an attack site.

The damage to the helmets suggested massive blunt force trauma.

The blood patterns indicated severe injuries occurred here.

Most significantly, animal scat found near the site contained human remains.

DNA testing confirmed it matched Jason Whitaker and Chad Reynolds.

The conclusion was inescapable when Jason and Chad tried to leave the ravine on September 3rd.

They encountered something that killed them violently.

Wildlife experts from the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission examined all the evidence.

Black bears inhabit the Pisca National Forest, but fatal attacks on humans are extremely rare.

The last documented black bear killing in North Carolina had occurred in 1936.

However, Dr.

Kenneth Walsh, a wildlife biologist with 40 years of experience, told investigators that desperate circumstances can change animal behavior dramatically.

A bear protecting cubs or a food cache might attack aggressively.

The ravine’s geography created a natural trap.

If Jason and Chad encountered a bear while climbing out, they had nowhere to retreat.

The helmet damage was consistent with powerful strikes from an animal.

The claw marks on clothing found earlier now made terrible sense.

Dr.

Walsh examined the scat evidence and confirmed it came from a large black bear, probably male, probably weighing 300 to 400 lb.

Such an animal could easily kill two adult men, especially in confined terrain where escape was impossible.

The theory fit the evidence, but it left investigators with more heartbreaking questions.

The last legible journal entries came from Tiffany’s notebook dated midepptember.

Her handwriting had deteriorated, words sometimes barely formed, suggesting extreme physical weakness.

One entry read Amanda and I heard them.

Jason and Chad screaming.

We heard everything, but we were too far away.

Couldn’t help.

Something attacked them.

We heard the animal, heard their screams stop.

We stayed at camp, terrified.

That was 4 days ago.

We haven’t seen any sign of Jason or Chad.

We know they’re dead.

We’re trapped here.

If we try to leave, the same thing that killed them will kill us.

We have no food.

Drinking water from the stream.

Getting so weak.

Amanda stopped talking yesterday.

Just stares.

I think she’s given up.

I don’t know what to do.

I don’t want to die here, but I’m too weak to climb out and too scared to try.

The words painted a picture of unimaginable horror.

Two women alone, starving, traumatized, trapped by fear of the animal that had killed their friends.

The last words ever written by any member of the group came from Tiffany’s journal, dated September 20th, 1998.

The writing was nearly illeible.

Letters barely scratched onto the page.

It read, “Amanda died today.

Just fell asleep and didn’t wake up.

I think starvation.

I buried her like we buried Eric.

Piled rocks.

I’m alone.

Too weak to climb out even if I wasn’t afraid.

Can’t stand up without getting dizzy.

Drinking water, but water isn’t enough.

I can hear the bear sometimes at night, snuffling around the campsite.

It knows I’m here.

Maybe it’s waiting.

I keep thinking someone will find us.

All this equipment, someone has to find it eventually.

If you’re reading this, tell my sister Nicole that I love her.

Tell her I tried.

Tell all the families we tried.

We just made one wrong turn and it cost us everything.

I don’t think I’ll write again.

Too tired.

The dates might be wrong.

I lost track.

I’m sorry.

After that, nothing.

No more entries.

No more words.

Just silence.

Based on the journal evidence, investigators launched an intensive search of the ravine for human remains.

They knew Eric had been buried under rocks near the campsite.

They found that site about 30 ft from the bikes.

Rocks had been piled carefully, forming a car about 4 ft high.

Carefully removing stones, they found skeletal remains underneath.

Forensic analysis confirmed the skeleton was male with evidence of a severely fractured tibia, Eric Dawson’s injury.

They found similar rock cars nearby where Amanda and Tiffany had been buried.

The women had done their best to honor their friends, even while dying themselves.

But finding Tiffany and Amanda’s remains proved far more difficult.

The ravine had experienced numerous landslides and floods over 13 years.

Small skeletal fragments were scattered across a wide area.

It took weeks of careful searching, but eventually forensic teams recovered enough remains to confirm that Amanda Keller and Tiffany Moral’s had indeed died in the ravine.

The DNA evidence was conclusive.

All five bikers had perished in that remote location between mid August and late September 1998.

This answers the second openloop question.

What explained the condition of the gear found scattered across the remote ridge? The answer was both natural and tragic.

Over 13 years, weather, landslides, and animal activity had scattered the carefully arranged campsite.

The bear that killed Jason and Chad had almost certainly returned to the camp multiple times, scavenging what it could.

This explained why clothing was torn and scattered.

The spring floods that swept through the ravine each year had moved lighter objects downstream.

Heavier items like the bikes stayed relatively in place, though they’d shifted position.

The arrangement investigators found in 2011 bore little resemblance to how the camp looked in 1998, but the forensic team found evidence that the group had maintained the camp meticulously in their final weeks.

They’d organized equipment, kept a clean sight, and maintained hope that rescue would come.

The scattering came later after they were gone.

As nature reclaimed the space, the Gears condition told a story of time passing, weather eroding, and wildlife interacting with human artifacts until evidence of five lives was reduced to rust and fragments.

This answers the third and most disturbing openloop question.

Why did forensic analysis suggest the group had survived for days after vanishing? The answer was they survived for weeks, not days.

Between August 14th, when Jason made his last phone call, and late September, when Tiffany likely died, at least 5 weeks passed, the group lived in that ravine for over a month.

Trapped by injury, fear, failed rescue attempts, and eventually by starvation and trauma.

Forensic analysis of the remains confirmed prolonged survival.

Eric’s bones showed infection markers consistent with fighting a severe wound infection for weeks.

Amanda and Tiffany’s remains showed extreme indicators of malnutrition and dehydration over an extended period.

The journals provided the timeline, but physical evidence confirmed it.

Perhaps most haunting was the evidence that Jason and Chad survived about three weeks in the ravine before attempting their fatal departure.

During that time, search teams were combing the forest, sometimes passing within a quarter mile of the ravine.

The group could occasionally hear helicopters, but couldn’t signal them.

They survived long enough to see hope fade and fear replace it.

When investigators briefed the families on findings in August 2011, the conference room at the sheriff’s department held a grief so thick it felt physical.

Karen Wetaker heard how her husband had survived for three weeks in that ravine, how he’d tried to save everyone, how he’d been killed trying to get help.

Michelle Torres learned that Eric had died from infection.

After weeks of suffering, trying not to burden his friends, William Reynolds discovered his son, Chad had volunteered to make the dangerous journey out despite knowing something was wrong.

Robert and Susan Keller heard their daughter Amanda had stayed to care for the injured, had died trying to help, had been buried by her friend.

Nicole Moral’s learned her sister Tiffany had survived the longest, alone, terrified, had written those final words before dying.

The families wept.

They’d waited 13 years for answers.

The answers were somehow worse than the not knowing.

But there was also terrible relief.

They finally understood.

The mystery that had tortured them was solved.

Their loved ones hadn’t abandoned them, hadn’t met some quick, painless end.

They’d fought, survived, hoped, and finally succumbed to circumstances beyond their control.

Wildlife officials investigated what happened to the bear that killed Jason and Chad.

based on territory patterns and DNA from the scat evidence.

Doctor Walsh believed the bear was a large male that had established territory in that area in the mid 1990s.

Black bears are not typically aggressive toward humans, but several factors might have triggered the attack.

The bear may have been defending a food cache or territory it considered crucial for survival.

The ravine’s confined geography escalated normal defensive behavior into fatal violence.

Most significantly, by September, the bear would have been entering hyperagia, the period before hibernation when bears eat constantly to build fat reserves.

A desperate, hunger-driven bear encountering humans in its territory could react aggressively.

Tracking records showed no bear attacks in that area after 1998.

The bear likely died of natural causes years ago.

Doctor Walsh emphasized to reporters that vilifying the animal served no purpose.

Black bears are generally peaceful.

This was a tragic confluence of circumstances, not a dangerous predator stalking humans.

A detailed review examined why search operations in 1998 failed to find the ravine.

The answer came down to a combination of factors.

The ravine sat just outside the search grid’s primary focus area.

Searchers had passed within 700 to 800 ft of the location multiple times, but the terrain between the trail and ravine was extremely difficult to navigate.

The ravine’s geography made it nearly invisible.

Dense overhead vegetation blocked aerial detection.

The steep sides and narrow entrance meant someone could walk past 20 ft away and never notice it.

Search operations had focused on trails and known camping areas, following established patterns of where lost hikers usually end up.

The ravine was too far off trail to fit normal lost person behavior patterns.

Statistically, the search protocol made sense, but statistics failed Jason’s group.

Ranger Patricia Wells took the findings hard.

She had done everything right according to procedure, but five people had died anyway.

She told investigators she would carry that weight for the rest of her life.

Sometimes your best efforts aren’t enough.

That truth offers no comfort.

Several families initially discussed potential lawsuits against the Forest Service for inadequate search operations.

After reviewing the analysis, most decided against it.

The search had been thorough by any reasonable standard.

The ravine’s location made it nearly impossible to find without specific coordinates.

No negligence had occurred.

Karen Whitaker publicly stated that blame served no purpose.

Her husband had chosen to go into the wilderness knowing risks existed.

The tragedy resulted from terrible luck and circumstances, not from anyone’s failure.

That said, she pushed for policy changes.

She worked with the National Park Service and Forest Service to improve emergency communication requirements for backcountry permits.

She advocated for better GPS beacon technology and mandatory check-in protocols for groups traveling in remote areas.

Several changes were eventually implemented, partly because of her advocacy.

if those five deaths could prevent future tragedies through better safety protocols.

Karen believed it gave some meaning to senseless loss.

Not comfort, never comfort, but at least meaning.

In September 2012, a permanent memorial was installed at Davidson River Campground near the spot where the five bikers had last been seen alive.

The memorial consists of a bronze plaque mounted on a large stone surrounded by five smaller stones, one for each lost biker.

The plaque reads in memory of Jason Wetaker, Eric Dawson, Chad Reynolds, Amanda Keller, and Tiffany Moral’s who entered these mountains in August 1998 and never returned.

They died as they lived together, courageous, caring for one another until the end.

May their story remind us that wilderness, while beautiful, demands respect and preparation.

May we honor them by cherishing each day and the people we love, the families gathered for the dedication ceremony.

Over 300 people attended.

The event was quiet, somber, healing.

Nicole Morales read her sister’s final journal entry aloud, her voice breaking on the words, “Tell her I tried.” Karen Wetaker planted five mountain laurel bushes near the memorial, one for each person.

She said they would bloom every spring, a reminder that beauty persists, even in places touched by tragedy.

The case of the five missing mountain bikers was finally closed in November 2012.

All remains had been recovered, identified, and returned to families for burial or cremation.

The investigation concluded that the deaths resulted from accidental injury followed by complications including infection, starvation, and fatal wildlife encounter.

No criminal activity occurred.

The ravine where they died remains as it was a remote scar in the mountain side that holds echoes of desperate days and final breaths.

Hikers occasionally make the difficult journey to see the location, though officials don’t publicize exact coordinates out of respect for the families.

The bikes and equipment were returned to the families.

Karen keeps Jason’s helmet, dented and rusted, on a shelf in her study.

She says it reminds her that life is fragile, that we’re never as safe as we think, that the people we love can vanish between one breath and the next.

13 years they waited for answers.

The answers brought grief, but also closure.

Now, the question that haunts anyone who hears this story isn’t what happened.

We know what happened.

The question is simpler and more terrible.

What if the search grid had extended just 800 ft further? What if one helicopter had flown a slightly different pattern? What if what if what if sometimes the crulest truth is that tragedy comes down to 800 ft and blind luck and there’s no one to blame but chance itself.

And chance, as we all know, never apologizes.

This disappearance mystery reminds us why missing person cases captivate us.

They reveal how quickly lives can vanish without a trace.

Like many cold case files and unsolved mysteries, this story shows the devastating reality families face when someone disappears under mysterious circumstances from the Appalachin Mountains to wilderness areas worldwide.

Missing persons investigations continue as people search for vanished loved ones.

These true crime stories and suspenseful disappearance mysteries teach us that preparation matters in remote terrain.

Whether it’s missing men, missing women, or entire groups, each case demands attention.

If you’re drawn to crime documentaries, unsolved disappearances, and real life mystery stories about people who disappeared and were found years later.

Subscribe for more haunting tales of those who vanished and the investigations that finally brought answers.

News

The men Disappeared In The Appalachian Forests.Two Months Later, Tourists Found Them Near A Tree

In September of 2016, two 19-year-old students with no survival experience disappeared into the Appalachian forests after wandering off a…

The men Disappeared In The Appalachian Forests.Two Months Later, Tourists Found Them Near A Tree

In September of 2016, two 19-year-old students with no survival experience disappeared into the Appalachian forests after wandering off a…

She Disappeared On The Appalachian Trail.Four Months Later A Discovery In A Lake Changed Everything

In April 2019, 19-year-old student Daphne Butler set off on a solo hike along the Appalachian Trail in the Cherokee…

Three Teenagers Went Missing In Arizona.Nine Months Later, One Emerged From The Woods

Three Teenagers Went Missing In Arizona. Nine Months Later, One Emerged From The Woods On March 14th, 2018, three teenagers…

Three Teenagers Went Missing In Arizona.Nine Months Later, One Emerged From The Woods

On March 14th, 2018, three teenagers got off a bus at an inconspicuous stop in the pine forests of Arizona….

She disappeared in the forests of Mount Hood — two years later, she was found in an abandoned bunker

In September 2020, a group of underground explorers wandered into a remote ravine on the northern slope of Mount Hood…

End of content

No more pages to load