There is nothing more strange than human disappearance, not death, disappearance itself.

When the body is not found, the soul seems to hang between worlds.

Then the question where becomes scarier than why.

Especially when 5 years after the disappearance, one of the three returns with hell in his eyes and an incredible story on his lips.

The Cambodian jungle, July 23rd, 2023.

in the morning, the sun had just begun to penetrate the thick canopy of the Cardamom Mountains when Sockchand, a local farmer from the village of Preule, noticed a shadow creeping out of the darkness of the jungle.

At first, Sock mistook the figure for a wounded deer or perhaps a disoriented Macak.

But as the shadow drew nearer, the farmer saw the impossible.

It was a human being.

The man who emerged from the forest could barely stand.

Long tangled hair hung in dirty strands down to his shoulders.

His clothes were reduced to rags through which his body, covered with scars and soores, was visible.

He dragged his right leg behind him, leaning on a homemade cane.

But the most frightening thing was his eyes, wide open with faded blue irises that seemed almost transparent against the background of inflamed red scara.

When the man saw SOA, he tried to scream, but only a horse whisper escaped his throat.

Help, American.

2 hours later, the police confirmed the stranger’s identity.

He was Garrett Hodgeges, a 26-year-old graduate student from the University of Oregon who had disappeared along with two other students, Wesley Tanner and Caleb Nichols, in this very jungle 5 years ago.

5 years ago, on May 28th, 2018, three young anthropologists arrived in Prel to study ancient Camar ruins and the culture of the indigenous tribes of the Cardamom Mountains.

All three were promising scholars united by a common research program under the guidance of Professor Randall White, a renowned anthropologist with 30 years of experience in Southeast Asia.

The three Americans were last seen on June 13th when they set off into the jungle accompanied by a local guide.

According to the guide, who returned alone the next day, the students insisted on continuing the journey on their own after a disagreement about the route.

No one paid much attention to this until their return date passed.

A large-scale search lasted 3 months.

Cambodian army units, rescue teams, helicopters, search dogs, everything was mobilized to find the missing Americans.

The investigation reached a dead end after the trail went cold near the Aaron River, 10 mi from the village.

The official search operation was called off in October of that year and the case was classified as a disappearance under unknown circumstances.

Unofficially, the police suspected an accident, an attack by wild animals or possibly a clash with poachers.

5 years of silence, 5 years of uncertainty for the Hodgeges, Tanner, and Nicholls families.

And now an unexpected return.

One of the three.

In a hospital in Ponam Pen under police guard and in the presence of a representative of the US embassy, Garrett Hajes refused to speak for 3 days.

On the fourth day, he asked for a pen and paper and wrote only one sentence.

They know I’m back.

On the fifth day, he spoke and his story shook even the most experienced investigators.

I saw them die, Garrett began in a quiet, broken voice.

But now I’m not sure if they’re really dead.

This was just the tip of the iceberg of a story that changed the entire direction of the investigation and forced a re-examination not only of the circumstances surrounding the disappearance of the three young scientists, but also called into question the safety of the entire Cardamom Mountains region.

What began as a routine scientific expedition turned into something much darker and more terrifying than anyone could have imagined.

The University of Oregon located in Eugene was known for its strong anthropology program.

It was here under the majestic pines and redwoods of the university campus that the paths of three young researchers Garrett Hodgeges, Wesley Tanner, and Caleb Nichols crossed.

Garrett Hodes, 21, was born in Spokane, Washington, to a doctor and a teacher.

Tall, thin, with piercing blue eyes and blonde hair, he always stood out among his peers for his focus and stubbornness.

According to Professor Randall White, the academic adviser of three students, Garrett was the type of student who doesn’t just study a subject, he lives it.

His specialization in linguistic anthropology and ethnography earned him a fullbrite scholarship in his third year of study.

He could sit in the library for hours forgetting to eat or sleep, said his mother, Marilyn Hajes.

We joked that he spent more time with dead languages than with living people.

Wesley Tanner, 22, was the complete opposite of Garrett.

Born in Portland, Oregon, he grew up in a family that owned a chain of tourist shops.

Strongly built with short dark hair and a constant smile, Wesley was the life of any party.

His major was social anthropology.

Unlike Garrett, who was fascinated by theory, Wesley preferred field research.

A year and a half before the fateful expedition, he spent 6 months among tribes in Papua New Guinea studying their initiation rituals.

He always said that textbooks only show a shadow of real life, recalled his ex-girlfriend Emily Woods.

Wesley wanted to experience culture through touch, taste, and smell.

The third member of the trio was Caleb Nichols, 23, from Seattle, Washington.

Of average height, with curly brown hair and thin rimmed glasses, he was the oldest and, oddly enough, the most level-headed of the three friends.

The son of an archaeologist and an archaeologist himself by training.

Caleb inherited not only his father’s profession but also his methodical thinking.

He specialized in Southeast Asian archaeology, researching the mutual influences of Camair and Cham cultures.

Caleb was the one who always double-cheed all the details, said Professor White.

If they were working on a joint project with Garrett and Wesley, Caleb was always their anchor, the one who brought the dreamers back down to Earth.

They were brought together by a seminar on the ethnoarchchaeology of Southeast Asia in their second year of study.

After 2 years of joint research and discussions, they became not only colleagues but also close friends.

Often referred to at the university as the three musketeers of anthropology.

They complimented each other.

Garrett was a theorist, Wesley was a practitioner, and Caleb was a systematizer.

Together, they published two articles in student scientific journals that attracted the attention of professors.

The idea for the expedition to Cambodia came from Professor White, who had been working in the region since the 1980s.

The official goal was to study the little researched Camair temples of the Ankor period in the remote areas of the Cardamom Mountains and to study the interaction of modern indigenous communities with these monuments.

The University of Oregon in partnership with the Royal University of Ponam Pen received a grant for this project from the National Geographic Society.

Preparations for the expedition took almost a year.

Students studied the Camar language, the history of the region, and the basics of jungle survival.

They underwent medical examinations and received the necessary vaccinations, including for malaria and Japanese encphilitis.

The process of obtaining permits was long and complicated.

Despite the growth of tourism, Cambodia remained a country with bureaucratic obstacles to scientific research, especially in remote areas.

The students equipment was carefully selected for a long stay in tropical conditions.

Lightweight but durable clothing, waterproof backpacks, special jungle boots, insect repellents, water filters, satellite phones, and GPS navigators.

The total weight of the equipment for each person was about 40 lb.

2 weeks before departure, Wesley wrote in his diary, “Tomorrow we will receive the final permits.” Caleb is nervous about the bureaucracy.

Garrett is nervous that we may not be allowed to visit some of the temples.

And I just can’t wait to see places that only the jungle knows.

Professor White says that our expedition could change our understanding of the peripheral centers of Camair culture, and I believe it will.

In the last few days before departure, all three kept in close contact with their families.

Garrett called his mother every evening to tell her about the latest preparations.

The day before departure, he sent her an email with a detailed itinerary and research plan.

“Don’t worry, Mom,” he wrote.

“The region is completely safe.

The locals are friendly, and predators that pose a threat to humans have not been seen in these parts for a long time.” Wesley was less detailed in his communication with his parents.

“Everything’s great, Dad.

I’m packing gallons of sunscreen,” his last message said.

However, he sent a longer message to his girlfriend, Emily, admitting that he was a little nervous.

Of course, it’s not Papua, but still, the jungle is the jungle.

Yesterday, I read about Cambodia’s poisonous snakes.

Now, my dreams will be more fun.

Caleb, as always, was the most organized.

He compiled a detailed document for his parents with the contact details of all the guides, hotels, and university partners in Cambodia, a call schedule, and even a list of possible emergencies and algorithms for action in such cases.

Just being cautious, he explained in his last conversation with his father.

Although in reality, the biggest danger is that Wesley will drag us and Garrett to some rural party instead of work.

On May 27th, 2018, the trio flew from Portland to Penamp Pen with layovers in San Francisco and Hong Kong.

At the Ponam Pen airport, they were met by a representative of the Royal University, Dr.

Sophi Chan, who helped with customs formalities and hotel accommodations.

They spent the next 3 days in the capital finalizing the details of the expedition, purchasing supplies, and meeting with Cambodian students who would be joining them later.

On June 1st, the group set off for the northwest of the country to the province of Kong where the Cardamom Mountains are located.

The journey was not easy.

First, they traveled by minibus for about 6 hours on the highway, then switched to an older and less reliable jeep to travel on dirt roads.

The last part of the journey, about 15 mi, had to be covered on foot with local porters helping with the luggage.

They arrived in the village of Preol on June 3rd, exhausted but full of enthusiasm.

The village located on the edge of the jungle was their last point of contact with civilization before plunging into the wilderness.

Here they were to meet their chief guide, 50-year-old Chuang Soo, who had lived in the region all his life and knew both the terrain and the indigenous communities well.

From the village, Garrett sent his mother a final message.

The jungle is very close, literally outside our window.

At night, you can hear amazing sounds from crickets the size of my palm to some distant cries, which I hope belong to monkeys.

The locals say that there are temples in the mountains that are not on any map.

Chang promises to show us one in a few days walk.

The connection here is weak, so I’ll write again when we return from our first excursion.

It will take about 10 days.

Those 10 days stretched into 5 years for Garrett Hajes and into eternity for his friends.

June 7th, 2018.

The village of Preuol was slowly waking up, enveloped in the damp haze of a tropical morning.

Before dawn, the three American students had already packed up their tents, checked their equipment, and recharged their electronic devices one last time from the generator in the village chief’s house.

Lansoka, owner of the only shop in the village, later testified.

They looked excited, but not anxious.

Wesley, the tall, strong one, bought extra batteries and canned food.

He joked with the local children and showed them photos of American landscapes on his phone.

Garrett, the thin one with blonde hair, wrote something down in a notebook, asking me through an interpreter about legends associated with the mountains.

The third, Caleb, was quieter, checking maps and talking to Changang about the route.

Chuang Sot, a 50-year-old guide with 30 years of experience hunting and gathering medicinal herbs in the jungle, was preparing his own equipment.

Witnesses noted that he seemed unusually tense that morning.

Chang was born in these mountains and knows them better than his own home, recalled the village chief of Prel.

But that day he smoked one cigarette after another and refused to look toward Mount Arrol.

Mount Errol, a hill about 2,000 ft high, towered 8 mi from the village.

The locals considered it a place where spirits lived and rarely climbed above a certain limit.

According to Chuang, it was there that the ruins of a small Camair temple not marked on official maps were located.

At 9 in the morning, the group set off.

In addition to the three Americans and Chuang, they were joined by two porters, young men from the village who were to help carry the load to the first camp and then return.

According to the plan, the expedition was to last 10 days.

3 days to reach the temple, 4 days for research, and three days for the return trip.

A photograph taken by Wesley just before departure is the last image of the three friends.

In it, Garrett, Wesley, and Caleb stand near a sign with the name of the village, smiling, dressed for the jungle, light but dense clothing, wide-brimmed hats, and high boots.

On the first day, the group traveled about 12 mi along the PreSong River, gradually penetrating deeper into the increasingly dense jungle.

The porters later reported that the group’s spirits were high despite the humid heat and clouds of mosquitoes.

The only thing that was surprising was that the guide, Choen, stopped from time to time to look closely at markings on the trees, which according to him hadn’t been there before.

They stopped for the night in a small valley a mile from the river.

They set up three tents, one for the students, one for the guide and porters, and one for the equipment and samples they plan to collect.

Chang showed the Americans how to set up the camp to deter snakes and wild animals.

On the morning of June 8th, the porters headed back to the village, leaving four men to continue the journey.

That same evening, the porters safely returned to Preol.

What happened in the following days is known only from Changang’s words and fragmentaryary electronic evidence.

On June 9th, the group crossed the Kraven Ridge and reached the foot of Mount Arrol.

According to Chuang, they planned to climb the next day.

On June 10th, around noon, they began their ascent of Mount Arrol.

The heat was unbearable and the humidity was almost 100%.

Caleb began to fall behind due to knee pain which had worsened after yesterday’s descent from the ridge.

However, he insisted on continuing the route.

Towards evening, when they had climbed about 1,000 ft, Chong discovered a dangerous landslide on the planned route.

He suggested turning back and going around the mountain from the other side, which would mean an extra day of travel.

According to him, that’s when the argument started.

Garrett and Wesley insisted on continuing the climb straight ahead.

Chang told the police, especially Wesley.

He said the landslide looked old and stable and we could carefully pass through it.

Caleb agreed with me.

It was too risky.

But then something strange happened.

Garrett stepped aside and began examining a carved stone.

Then he called the others over.

They talked at length in English which I didn’t understand.

When they returned, the mood had changed.

Now all three insisted on continuing straight ahead, even Caleb.

According to Chuang, the argument lasted almost an hour.

He categorically refused to take the dangerous route.

In the end, the students suggested that he returned to the village while they promised to proceed cautiously, stick to the plan, and return in 8 days.

I didn’t want to leave them, Chuang testified.

But all three of them were adults.

They had GPS, maps, satellite phones.

The route was marked on the map.

They insisted they could handle it.

And Garrett repeated several times that they weren’t going to make a fuss if they found something important.

It sounded strange.

On the morning of June 11th, Chang headed back to the village, leaving the students at the foot of Mount Arrol.

This was the last confirmed sighting of Garrett Hodgeges, Wesley Tanner, and Caleb Nichols.

Cho returned to Preall on June 14th, a day later than planned, explaining the delay by a heavy rainstorm that had washed out the trails.

On June 13th, at a.m.

Pacific time, Professor Randall White, the group’s scientific director, received a strange message on the expedition’s satellite phone.

The message consisted of two parts.

The first was obviously written by Garrett Prof.

We found something amazing.

It’s not exactly what we were looking for, but it might be more important.

Coordinates 11589 103.456.

There’s nothing on the map, but we found a depression in the rock that leads to the second part of the message was a fragment.

Typed in what seemed to be a hurry.

Doesn’t look like Camair.

Maybe older or I hear sounds.

Kay says we should go back, but V insists.

Strange markings on the walls like, “Oh my god, it’s moving.

What is it?” The message ended there.

Professor White immediately tried to contact the group, but the satellite phone did not respond.

He called his contact in Ponam Pen, Dr.

Sophi Chan, but he said that according to the plan, the expedition was not due to return for another week and that such communication interruptions in the mountains were common.

They decided to wait until the scheduled return date before raising the alarm.

Meanwhile, strange events were unfolding in the village of Preuol.

On the same night that the last message was sent, several villagers were awakened by unusual sounds coming from Mount Aral.

“It didn’t sound like an animal cry,” said Paul Rotana, one of the villagers.

It was more like a vibration, a low hum that turned into a high-pitched whistle, and it lasted for almost an hour.

My chickens went crazy with fear, and my dog hid under the house and refused to come out until morning.

Another villager, old men Sivatha, claimed to have seen a green light rising from the mountain to the sky, like a stream of water only upwards.

No one else confirmed this observation, and the police later classified it as unreliable evidence.

When the expedition’s return date passed, and Chong began to express concern, Dr.

Chan organized the first search party.

On June 22nd, four rangers from Cardamom Mountains National Park along with Chang set out on the trail of the missing expedition.

3 days later, they reached the Americans last campsite about a mile from the foot of Mount Arrol.

What they found only deepened the mystery.

The camp looked as if it had been abandoned in a hurry.

The tent was still standing, but had been partially destroyed, possibly by heavy rain or animals.

Inside were sleeping bags, food supplies, and some equipment.

Garrett and Caleb’s backpacks lay next to the tent, almost untouched, only slightly damaged by small rodents.

Wesley’s backpack was not found.

The most disturbing find was a satellite phone smashed to pieces, as if someone had deliberately destroyed it.

Garrett’s notebook lay nearby, the last entries dated June 12th.

The markings on the stone match the description of pre-ankoran writing in Julian’s works.

We need to make a complete record and compare it with the archives.

Wesley says he saw similar symbols on the ascent, but I didn’t notice them.

We’ll check tomorrow.

Caleb is concerned.

He says the terrain doesn’t match any records of temples in this region.

If we find something significant, it could change our understanding of Camar peripheral architecture.

The last entry was cut off mid-sentence.

Something strange is happening with the compasses.

The needles are spinning as if on the ground near the tent.

They found trampled footprints leading toward the mountain.

The rangers tried to follow them, but after 400 yd, the tracks disappeared on the rocky ground.

The search party returned to the village and reported their findings.

The next day, a full-scale rescue operation was organized.

Three young Americans had disappeared in the heart of the Cambodian jungle, leaving behind more questions than answers.

News of the disappearance of three American students quickly spread around the world.

On June 26th, 1978, the regional authorities of Kokong Province declared a state of emergency and launched a large-scale search operation.

50 police officers, 20 rangers from Cardam Mountains National Park and 30 volunteers from nearby villages formed the largest search party in the region’s history.

We have never faced a situation like this, admitted Colonel Kim Sochi, the provincial police chief.

Our mountains are huge, the roads are confusing, and the jungle is so dense that sometimes you can’t see the sky.

Finding three people in such conditions is like looking for three grains of sand in the desert.

But we didn’t give up.

Initially, the search operation focused on the expedition’s last known location, an abandoned camp at the foot of Mount Arrol.

Search teams spread out from there in a radial pattern, checking every ravine, every gorge, every cave within a 3m radius.

The coordinates given in Garrett’s last message led to a rocky slope half a mile from the camp, but nothing remarkable was found there.

No temple, no cave, just a small natural depression in the rock that might have looked like a cave entrance from a distance.

By July 1st, more than 200 people were involved in the search.

The American embassy sent a consular officer and two crisis response specialists.

They set up their headquarters in the village of Prel, turning the mayor’s house into a temporary coordination center.

On July 2nd, FBI specialists Michael Devo and Sarah Lynn arrived, both with experience in search operations in difficult natural conditions.

The parents of the missing students flew in with them.

“My son is an experienced traveler,” said Robert Tanner, Wesley’s father, at an impromptu press conference.

“He spent 6 months in the jungles of New Guinea.

If anyone knows how to survive in the wild, it’s him.

We’re not giving up hope.

At this point, the search operation encountered its first serious obstacles.

The monsoon season had begun.

Daily downpours lasting several hours turned dirt roads into impassible swamps, washed away tracks, and forced rescuers to spend more time in shelters than searching.

Rivers overflowed, cutting off some areas of the jungle from the main forces.

“We couldn’t use helicopters for the first two weeks,” Michael Devo recalled.

Visibility was zero due to clouds and rain.

When the weather finally improved a little, the pilots had to maneuver between hills in strong gusts of wind.

It was an extremely risky operation.

Another problem was the language barrier.

Most of the local rescuers spoke only Camair and some spoke dialects of the region’s indigenous peoples.

American and international experts needed interpreters who were in short supply.

This made coordination difficult and sometimes led to dangerous situations due to misunderstandings.

The local wildlife added to the difficulties.

During the search, two rescuers were bitten by poisonous snakes.

One broke his leg after falling into a hidden pit and several others had to be evacuated due to malaria and tropical fever.

On July 12th, dog handlers from Thailand joined the operation, bringing four specially trained search and rescue dogs.

The dogs were given the students personal belongings from the abandoned camp to sniff, and they immediately picked up a trail leading northeast from Mount Arrol to the Stung Poey River.

The dogs were extremely excited, said Samchai Ratanapuk, chief dog handler.

They pulled so hard that they almost broke their leashes.

This meant that the trail was strong and clear.

However, at the riverbank, which had been transformed into a raging torrent nearly 40 yards wide by the monsoon rains, the dogs lost the trail.

They ran along the bank whining, but could not determine the direction.

The dog handlers explained that the water was washing away the scent, and if the students had crossed the river, the dogs would not be able to find the trail on the other side.

rescuers crossed the river and tried to put the dogs back on the trail, but the animals could not pick up the scent.

This meant that either the students had not crossed the river, or there was too little of a trail left to detect.

At the end of July, when the weather had stabilized somewhat, a full aerial scan of the area was finally possible.

Two helicopters equipped with thermal imaging cameras and highresolution cameras surveyed an area of over 200 square miles over the course of a week, but the results were disappointing.

“We found no signs of human presence,” said Captain James Wilson, head of the aerial search team.

“No fires, no tents, no cleared areas.

The only thing we saw was a few small buildings at the foot of the eastern slope of the Kraven range, but these turned out to be temporary huts belonging to local cardamom spice gatherers.

In August, the operation encountered its first false leads.

A resident of the remote village of Trapeang Rang, located 30 mi east of Mount Aral, claimed to have seen three foreigners buying food and medicine from a local healer.

According to his description, they could have been the missing students.

A rescue team immediately traveled to the village, but after questioning witnesses in detail, it became clear that they were French tourists traveling in the region who knew nothing about the missing Americans.

Another false lead was an anonymous call to the US embassy from a person who claimed to have seen three young Americans in Pam Pen alive and well.

According to the anonymous caller, they had deliberately staged their disappearance to avoid paying their tuition fees.

This version was quickly refuted.

None of the students had significant debts, and their bank accounts had remained untouched since their disappearance.

By September, the intensity of the search began to wne.

The monsoon season had reached its peak, turning the jungle into an almost impenetrable swamp.

The number of rescuers was reduced to 50.

The search area was expanded to a radius of 50 mi from the last camp, but this only scattered the forces.

The families of the missing students, who had been in Cambodia all this time, began to express dissatisfaction with the organization of the search.

It’s been 2 months and we still don’t have a single lead, David Nichols, Caleb’s father, said in an interview with CNN.

It seems that the local authorities are more focused on preserving their tourist image than on the actual search.

We demand that more international experts be brought in.

Cambodian authorities denied these accusations, pointing to the unprecedented scale of the operation and the difficult natural conditions.

On September 15th, exactly 3 months after the search began, the Kong provincial authorities officially suspended the large-scale operation, leaving only a small group of rangers to continue periodic patrols of the area.

We have exhausted all possible resources, explained Provincial Governor Mitt Finara.

In 3 months, we have searched every square yard of territory within a 30-m radius.

If the students were alive and moving, we would have found them.

If they had died in the jungle, we would have found bodies or remnants of equipment.

The official theory of the authorities was that the students had probably drowned while attempting to cross the Stung Poey River, which turned into a raging torrent during the rainy season.

The bodies could have been carried dozens of miles by the current and hidden in the mangrove thicket of the delta.

The families refused to accept this version.

They hired a private search company, Global Rescue, from Singapore, which specialized in searching for missing persons in difficult conditions.

Over the next 12 months, a team of eight specialists returned to Cambodia periodically to conduct independent searches and investigations.

During this time, they interviewed more than 300 local residents, checked dozens of rumors and reports of possible sightings, and explored several remote temples and caves not marked on official maps.

But this yielded no significant results.

The last major effort was a project to digitally recover data from a damaged satellite phone found at the camp.

Cyber crime experts at Stanford University worked on this for nearly 6 months, but were only able to recover a few fragments that contained no new information.

By the end of 2019, even the families had begun to lose hope.

Private searches were discontinued.

The case of the three missing American students was classified as unsolved under unknown circumstances.

At the consular section of the US embassy in Ponam Pen, its status changed from active to inactive.

The world gradually forgot about Garrett Hodgeges, Wesley Tanner, and Caleb Nichols until July 2023 when one of them unexpectedly returned from the jungle that seemed to have swallowed them up forever.

Time is an inexurable doctor and a ruthless executioner.

It heals wounds, but never brings back what has been lost.

5 years is a moment in historical perspective, but an eternity for those waiting for the return of their missing loved ones.

March 2023.

In Marilyn Haj’s house in Spokane, Washington, time seems to have stopped.

Her son Garrett’s bedroom has remained untouched since the day he left for Cambodia.

On the table is a stack of anthropology books, bookmarks still in the same pages.

On the wall is a map of Southeast Asia with markings for planned expeditions that were never to be.

“I know he’s alive,” Marilyn said in an interview for the documentary Lost in the Cardamom Mountains, released in early 2023.

“Mothers feel these things.

Sometimes at night, I dream of jungles I’ve never seen, and I hear Garrett’s voice calling me.

He’s out there somewhere, just waiting for the right moment to come back.

Marilyn never officially declared her son dead, refusing to initiate the procedure to declare him missing, which could be started under Washington state law 5 years after his disappearance.

She spent almost all her savings on private investigators and even visited Cambodia twice herself, most recently in December 2022.

The Tanner family coped with their loss differently.

Robert and Diana Tanner, Wesley’s parents, after a year of actively searching for their son, redirected their energy to helping other families who had faced similar tragedies.

They founded the nonprofit organization Find Your Way Home, which coordinated the search for missing Americans abroad and provided legal and psychological support to their families.

We decided that the best way to honor Wesley’s memory would be to help others, Robert Tanner explained during a charity event in Portland.

Our son always wanted to make the world a better place.

We are continuing his work.

In 2021, the Tanners agreed to have their son declared missing in action in order to receive an insurance payout, which they donated in full to the development of their charitable organization.

David and Susan Nichols, Caleb’s parents, chose a different path.

They completely isolated themselves from the public eye.

After several months of actively participating in the search and criticizing the Cambodian authorities, they suddenly stopped all public appearances and moved from Seattle to a small town in Idaho.

Rumor has it that they received some information about their son that forced them to stop the search, but there was no confirmation of this.

Meanwhile, the case of the missing students gained new life on the internet.

Numerous forums and subreddits dedicated to unsolved crimes and mysterious disappearances turned the Cambodian mystery into an object of obsessive interest for thousands of amateur detectives.

“The Cardamom case has become a kind of holy grail in the true crime enthusiast community,” said Jennifer Morgan, founder of the popular podcast Missing.

It has all the elements necessary to spark the imagination.

An exotic location, young promising victims, mysterious last messages, missing bodies, and a huge number of conflicting theories.

By 2023, at least six main theories about the fate of the American students had formed online.

The most popular version remained that of an accident, a tragic death in the jungle due to a fall from a cliff, an attack by a wild animal, or drowning.

Proponents of this theory pointed to numerous cases of tourists disappearing in Cambodia and neighboring Thailand, where dense jungles and fast flowing rivers often became deadly traps for inexperienced travelers.

The second theory, which was gaining popularity, claimed that the students had fallen victim to organized crime.

According to this version, they accidentally stumbled upon illegal activities, perhaps drug production or the smuggling of rare animals and plants, and were killed to prevent them from becoming witnesses.

Proponents of this theory cited words about strange markings on the trees and Garrett’s last message, which was cut off mid-sentence.

A third version offered an even more sinister explanation.

The students may have fallen victim to a Camar cult that allegedly operated secretly in the mountains.

This theory, although it had no factual basis, was based on historical information about syncric religious cults that combined Buddhism, animistic beliefs, and elements of ancient Camair paganism.

Several self-proclaimed experts claimed to have found in Garrett’s last message had found coded references to the ritual nature of what had happened.

The fourth theory was more prosaic.

The three students could have been victims of interpersonal conflict.

Proponents of this version pointed to a dispute that had occurred between members of the expedition and led to the return of the guide Changang.

Perhaps the conflict escalated after his departure and ended in tragedy.

However, this theory did not explain why none of the three returned to civilization.

The fifth version, which was considered the least likely, but still had its supporters, claimed that the disappearance was voluntary.

According to this theory, the students found something so valuable, perhaps archaeological artifacts or rare minerals, that they decided to stage their disappearance and start a new life under different names.

Supporters of this version pointed to the mysterious behavior of the Nicholls family who suddenly stopped searching and the absence of bodies which could indicate that the students were still alive.

Finally, the sixth theory, the most exotic, spoke of a supernatural disappearance.

Its supporters cited local residents reports of strange sounds and a green light rising into the sky on the night of the disappearance.

They also drew attention to Garrett’s words in his last message that it’s moving.

This theory spawned an entire subculture whose participants combined elements of folklore, paranormal research, and eupfology.

In January 2023, the independent studio Enigma Docs released an hour-ong documentary titled Lost in the Cardamom Mountains.

Director Alex Freeman spent nearly two years gathering material, interviewing witnesses, and researching the area.

The documentary was an unexpected success, winning a special jury prize at the Sundance Film Festival and attracting the attention of millions of viewers on streaming platforms.

We didn’t try to impose a particular version on the audience, Freeman explained in an interview with Rolling Stone.

Our goal was to present all the facts as objectively as possible, give all sides a voice, and let viewers draw their own conclusions.

The film reignited public interest in the case.

Several major media outlets published their own investigations.

New podcasts devoted entire seasons to analyzing the disappearance, and travel agencies in Cambodia even began offering tours of the sites of the mysterious disappearance of Americans, which outraged the families.

The University of Oregon also responded to the renewed interest in the case.

In March 2023, on the eve of the fth anniversary of the disappearance, the Hajes Tanner Nichols Memorial Scholarship was officially established for students who showed particular aptitude for fieldwork in anthropology.

The scholarship covered the full cost of tuition and a research grant, but with one important condition.

Scholarship recipients were not allowed to conduct research in the Cardamom Mountains of Cambodia.

“We have lost three extremely talented young scholars,” said University President Dr.

Elizabeth Chang during the memorial plaque unveiling ceremony.

“Their dedication to science, their curiosity, and their thirst for knowledge are an example to all our students.

This scholarship will ensure that their names and their values live on in future generations of researchers.

Professor Randall White, who was still working at the university, although he had reduced his teaching activities, was present at the ceremony.

Aged with deep wrinkles on his face and a dull look in his eyes, he held a worn notebook in his hands, the same one that had been found in his students abandoned camp.

I still reread Garrett’s last notes, he confessed to reporters after the ceremony.

I’m looking for something I might have missed, some clue.

They weren’t just my students.

They were the future of anthropology.

And despite everything, I still believe that one day we will learn the truth about what happened on Mount Arrol.

He didn’t know that his words would prove prophetic just 4 months later when an exhausted, traumatized, but alive Garrett Hodgeges would crawl out of the jungle near the village of Preu to tell a story that would change everything.

July 23rd, 2023 was particularly hot, even by Cambodian summer standards.

Sakchand, a 58-year-old farmer from the village of Preuol, went out to his rice field before dawn, hoping to finish his work before the scorching midday heat.

Few villagers dared to work at such hours when the air seemed thick with moisture and the sun mercilessly burned unprotected skin.

Around in the morning, as Sock was finishing checking the irrigation channels at the far end of his field, he noticed movement at the edge of the jungle.

At first, the farmer thought it was a wild animal, perhaps a deer or a macak.

But the figure moved strangely, almost humanly, though uncertainly.

“I felt fear,” Sock later recalled.

“Our area is full of stories about jungle ghosts, the spirits of those who died violent deaths and cannot find peace.

My first thought was to run away, but something about this figure made me stay.” The figure slowly approached, emerging from the shadows of the jungle into the light of the early sun.

Now Sock could see that it was indeed a human being, a man, but in such a terrible condition that he barely resembled a human being.

The tall, emaciated figure with long, dirty hair and a beard moved, leaning on a primitive staff.

His clothes had turned into rags that barely clung to his thin body.

The skin was covered with soores, scars, and strange patterns that looked like tattoos or ritual scars.

The man dragged his right leg behind him as if it were partially paralyzed.

But the most frightening thing, according to SOA, were the stranger’s eyes, blue like a ghosts, but red around the edges, as if filled with blood, and a gaze that seemed to see things no human should ever see.

When the man noticed the farmer, he stopped, swaying.

His cracked lips moved, but at first made no sound.

Then, gathering his last strength, he croked barely audibly.

American help, Embassy.

Sakchand rushed to the village for help.

Within an hour, the local police arrived, and another hour later, representatives of the district authorities and a medical worker.

The stranger was taken to the village clinic where he received first aid.

Despite years spent in the jungle and his terrible physical condition, he had a small leather wallet with him containing a faded but still legible Washington state driver’s license in the name of Garrett James Hodgeges.

By evening, the news had reached Penam Penn.

A representative of the US embassy and a police officer arrived by helicopter and confirmed the man’s identity by comparing his fingerprints with those stored in the missing person’s file.

There was no doubt this was Garrett Hajes, one of three students who had disappeared in the Cardamom Mountains 5 years earlier.

Garrett was immediately evacuated to the International Hospital of Panam Pen where a team of doctors conducted a full examination.

The medical report later published with the family’s permission described the patients condition as critical but stable.

The patient is suffering from severe exhaustion and dehydration, wrote Dr.

son Witchita, head of the medical team.

His weight is 40% below normal.

At least four types of intestinal parasites have been detected.

Chronic malaria, several healed but deformed fractures of the right tibia, which explains the limp.

Numerous scars, probably from cuts and burns.

On the right shoulder and back, there are scars that look like the marks of a large predator, possibly a leopard.

In addition, patterns of scars resembling deliberate ritual scars were found on the left forearm.

But physical trauma was only the tip of the iceberg.

Psychological evaluation revealed all the classic symptoms of severe post-traumatic stress disorder, hypervigilance, panic attacks, nightmares, moments of dissociation.

The patient reacts to certain sounds, especially low-frequency vibrations, with extreme anxiety, noted Dr.

Mary Lavine, an American psychiatrist called in by the embassy.

He also exhibits a strange mixture of symptoms.

Paranoid ideas combined with moments of absolute clarity of thought.

This condition is often seen in people who have experienced prolonged captivity or isolation in extreme conditions.

During his first three days in the hospital, Garrett did not say a word.

He responded to simple commands.

Open your mouth.

raise your hand, but ignored any questions about what had happened to him and where his friends were.

The only person he actively responded to was his mother, Marilyn Hajes, who flew to Punam Pen as soon as she received the news.

On the fourth day, Garrett suddenly asked for a pen and paper and wrote, “They know I’m back.” When doctors tried to find out who they were, the patient fell silent again.

On the fifth day, July 28th, in the presence of his mother, a consular officer, and a Cambodian police officer, Garrett finally spoke.

His voice was from prolonged silence, and his speech was fragmented, as if he had forgotten how to form complete sentences.

“I saw them die,” were his first words.

“But now I’m not sure if they’re really dead.” Over the next 2 hours, Garrett told a fragmented story of what happened after the guide Chaong left the three students at the foot of Mount Arrol.

According to his story, they found not just the ruins of a temple, but an entire underground complex, partly natural, partly man-made.

The entrance was hidden behind a waterfall that even the locals didn’t know about.

This was what Garrett had been trying to tell Professor White in his last message, which was cut off.

But they found more than just ancient artifacts in the tunnels.

Deep underground, there was a modern facility, something like a laboratory or factory, where, according to Garrett, some substances were being processed and people were being prepared.

There were people in white suits, he recalled, and guards with guns.

We weren’t supposed to see that.

No one was supposed to see that.

At this point, his story became even more confused and inconsistent.

He talked about the escape, the chase, how Caleb fell off a cliff trying to distract their pursuers, about Wesley being captured by people in masks.

He described how he managed to escape but was seriously injured.

“I couldn’t go back to the village,” Garrett explained.

“They control everything.

They have people everywhere, in the police, in the government, in international organizations.

I hid for years, moving from place to place, eating whatever I could find.

Several times I was found, but I escaped again.

The most shocking statement was his certainty that the laboratories were still operating and that people were being held there against their will, including foreigners.

I saw them, he insisted.

I heard their screams.

This isn’t just archaeological smuggling or drugs.

It’s something much worse.

The police officer and consular official listened to his story with obvious skepticism.

Medical staff noted that some of Garrett’s statements resembled the paranoid delusions typical of people with PTSD or psychosis.

We need to take into account that the patient spent 5 years in extreme conditions, suffered numerous injuries, and may have had episodes of psychosis due to malnutrition, infection, and isolation.

Dr.

Leaven cautiously noted his story may combine real events with hallucinations or dreams.

But Marilyn Hodgeges believed every word her son said.

“Look at his eyes,” she pleaded.

“This isn’t madness.

It’s fear.

The real fear of a man who has seen something terrible.” Gradually, over the next few days, Garrett began to provide more detailed and coherent information.

He described the complex with astonishing accuracy, naming names and dates, recalling details that a madman could hardly have invented.

Finally, the Cambodian authorities reluctantly agreed to verify the coordinates that Garrett had given as the location of the secret entrance to the underground complex.

This step changed everything.

On August 10th, 2023, a special unit of the Cambodian police accompanied by FBI agents and Interpol representatives traveled to the coordinates provided by Garrett Hodgeges.

At the insistence of the American side, the operation was kept strictly secret.

Only a few high-ranking officers knew its true purpose.

What they found confirmed their worst fears.

Behind the waterfall on the western slope of Mount Arrol, there was indeed a hidden entrance to a cave system, partly natural and partly man-made.

But the laboratory that Garrett had mentioned was gone.

Only empty rooms remained with signs of a hasty evacuation and deliberate destruction of evidence.

There were concrete structures, electrical cables, ventilation shafts, reported the team leader, Colonel Vthus Sura.

Everything pointed to a large-scale underground facility that had been in operation for many years, but almost all of the equipment had been dismantled or destroyed.

However, something remained.

In a far room, the team discovered what had once been a medical or laboratory area.

On the walls were traces of attached equipment, and on the floor were rusty stains that experts later identified as dried blood of varying ages.

Most importantly, they found physical evidence that finally confirmed Garrett’s story.

In a crack in the wall, behind a tornoff panel lay a sealed waterproof container.

And inside it was Wesley Tanner’s student ID from the University of Oregon and his personal diary with entries covering the period from the beginning of the expedition to June 14th, the day after their disappearance.

The last entry written in a shaky hand confirmed Garrett’s version.

We’re trapped.

This isn’t an archaeological site.

It’s some kind of underground complex.

We saw people in chains.

The guards are armed.

They know we’re here.

Caleb is wounded.

Garrett wants us to split up.

Better chance of someone surviving.

I hope it works.

If anyone finds this, please notify the American embassy.

People are being tortured here.

The evidence was irrefutable, but the coordinates were only checked after a two-week delay by the local authorities, and this time was obviously used to evacuate the complex.

Based on Garrett’s findings and testimony, the FBI and Interpol launched a joint investigation into what appeared to be an international criminal network involved in human trafficking, forced experimentation, and smuggling of archaeological artifacts.

According to the reconstruction of events compiled by investigators, the three students did indeed find ancient ruins.

But they also accidentally discovered a camouflaged entrance to an underground complex.

Out of scientific curiosity, they explored it and witnessed something they should not have seen, a large-scale operation involving the forced detention of people.

According to the investigation, the complex operated under the guise of an archaeological expedition financed by a fictitious international foundation.

In reality, it was a center of criminal activity, combining several areas, smuggling rare artifacts, producing new generation synthetic drugs, and most terrifying, conducting experiments on humans, possibly related to the development of biological weapons.

When the students were discovered, the guards were ordered to neutralize them.

Caleb Nichols died instantly after falling or being thrown off a cliff while fleeing.

Wesley Tanner was captured and according to Garrett, held in the complex for interrogation for at least several months.

Garrett himself managed to escape, but with serious injuries.

He found refuge in caves and later in remote villages where the locals, struck by his strange appearance and blue eyes, considered him a spirit and helped him with food, leaving offerings near his hiding places.

“I was neither alive nor dead,” Garrett explained to investigators.

“For almost a year, I was delirious from infections and injuries.

Sometimes I didn’t understand where I was or who I was.

I was afraid to return to civilization because I knew they would find me.

The most shocking discovery was the information about who was behind this operation.

An analysis of financial documents found in a hiding place Garrett had created in one of the caves revealed links to highranking officials in the governments of several Southeast Asian countries and top managers of multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

One of these documents, a page listing targets with various code names, including the name VT with a date corresponding to the time of Wesley’s disappearance, became key evidence in the international investigation.

Despite the strong evidence, the investigation constantly ran into obstacles.

Key witnesses disappeared or changed their testimony.

Documents were lost in bureaucratic red tape.

Police officers who were too active in pursuing the case were suddenly transferred to other regions.

In September 2023, the area around Mount Arrol suddenly received the status of a restricted access ecological reserve due to the discovery of rare species of flora and fauna.

In effect, this blocked the possibility of further investigations on site.

The most disturbing element of the case remained Garrett’s belief that the complex was not unique.

Similar facilities existed in other remote areas of Southeast Asia.

And what was particularly frightening was that he believed that Wesley and other subjects could have been moved to these other locations.

I heard them talking about transferring assets, Garrett insisted.

They didn’t kill everyone.

Some were taken away for something else.

Was Garrett right? Did other complexes exist? Could Wesley Tanner still be alive? There was no official confirmation of these claims.

But in October 2023, Interpol issued a wanted notice for nine individuals linked to a large-scale transnational criminal network involved in serious human rights violations.

Public details were limited, but sources close to the investigation confirmed that it all started with the testimony of an American student who had been missing in the jungles of Cambodia for 5 ears.

News

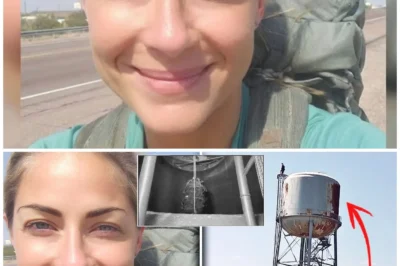

3 Years After a Tourist Girl Vanished, THIS TERRIBLE SECRET Was Found in a Texas Water Tower…

In July of 2020, a 22-year-old tourist from Chicago, Emily Ross, disappeared without a trace in the small Texas town…

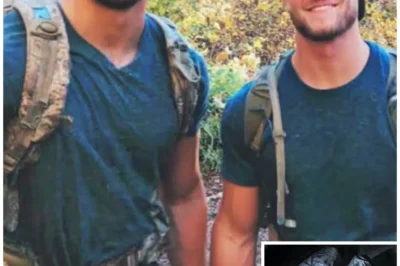

Brothers Vanished on a Hiking Trip – 2 Years Later Their Bodies Found Beneath a GAS STATION FLOOR…

In June of 2010, two brothers, Mark and Alex Okonnell, from Cincinnati, Ohio, went on a short hike in Great…

Backpackers vanished in Grand Canyon—8 years later a park mule kicks up a rattling tin box…

The mule’s name was Chester, and he’d been carrying tourists and supplies down into the Grand Canyon for 9 years…

Woman Vanished in Alaska – 6 Years Later Found in WOODEN CHEST Buried Beneath CABIN FLOOR…

In September of 2012, 30-year-old naturalist photographer Elean Herowell went on a solo hike in Denali National Park. She left…

Two Friends Vanished In The Grand Canyon — 7 Years Later One Returned With A Dark Secret

On June 27th, 2018, in the northern part of the Grand Canyon on a sandy section of the Tanto Trail,…

Boy And Girl Vanished In The Grand Canyon — 2 Years Later One Returned With A Terrible Secret

At dawn on September 23rd, 2023, Grand Canyon National Park Ranger Michael Ryder was conducting a routine patrol of the…

End of content

No more pages to load